Emily Mortimer on nepotism, Scorsese and the nude scene that changed how she feels about acting

The English actor has made a career in the US with roles in Shutter Island, 30 Rock and Mary Poppins Returns, but now as she plays a novelist in her best friend’s film, Good Posture, she tells Adam White about her years playing twisted people and how a cruel bedroom scene affected her

There was incest, wasn’t there?” Emily Mortimer is recalling her 1997 appearance as a wealthy killer in love with her brother in the very first episode of Midsomer Murders. “It was really f***ed up!” But, she insists, laughing, her entire early career was marked by playing “weird and twisted people”. “I had to give a guy a blow job for a gram of cocaine in Silent Witness and I had to literally spit out his come on the street. It was so shocking!”

It’s the sort of casually profane and bizarre anecdote that would be jarring to hear out of anyone’s mouth on a rainy weekday morning in a luxury London hotel. But even more so when it’s being spoken in the famously well-bred, cut-glass English voice of Mortimer. “One puts pressure on one’s self,” she says later, as if to subtly drive home that she can speak like the Queen, too.

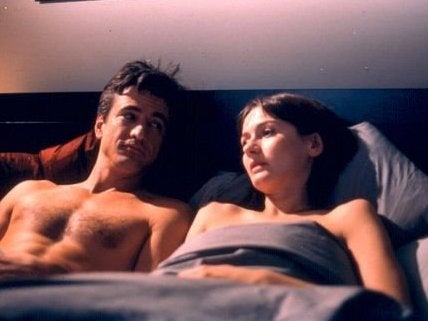

Those early roles, playing murderers, addicts and sex workers in British television melodramas, weren’t particularly sophisticated, but they did nod towards something about Mortimer’s range. For she has, in the years since, become a quietly extraordinary queen of metamorphosis, an actor regularly scooped up by our greatest living filmmakers and writers. She was as convincing as a rich woman with hollow bones like a pigeon in a recurring role on the Tina Fey comedy 30 Rock as she was a flustered and harried network news executive on Aaron Sorkin’s The Newsroom. There was also her haunting turn in Martin Scorsese’s Shutter Island, the time she was naked and smeared with condiments by Ewan McGregor in the murky thriller Young Adam, and, last year, her breezy charm as the grown-up Jane Banks in Mary Poppins Returns. Such variety has always made her difficult to pin down, yet equally one of the most exciting actors to watch.

She doesn’t actually appear very often in her new film, Good Posture, instead exchanging passive aggressive correspondence with the young film graduate (Grace Van Patten) who has moved in to her home. But Mortimer’s presence is all over Good Posture nevertheless, playing a spiky, reclusive novelist of incredible renown (Zadie Smith and Martin Amis provide deadpan cameos singing her praises), who slowly changes the life of her house guest. It is a lovely film, quiet and melancholy, but also stocked with barbed wit. It should come as no surprise, however, as it is the filmmaking debut of actor Dolly Wells, another Brit-abroad, most recently seen as a bookseller romantically interested in an emotionally distant Melissa McCarthy in Can You Ever Forgive Me?

Mortimer and Wells have been best friends since they were seven years old, after being thrust together via the friendship between their respective fathers: John Mortimer, the revered English treasure behind Rumpole of the Bailey, and John Wells, actor and satirist and one of the original contributors to Private Eye. Mortimer says she and Wells are “so close to the point where it’s almost weird”, and they’re both together on Mortimer’s press day for the film – Wells waving her goodbye from the corridor as she sits down to talk, and then picking her up again once our time is up. On the set of Good Posture, their closeness sometimes got them into trouble.

“Within two minutes, we’re in the loo gossiping about something completely unrelated to [the film], and the first AD is banging on the door saying we’ve got to get onto the set,” laughs Mortimer. “I can’t tell how much it is us together or her more than me, but there’s [always] something very chilled about it all. It’s never that feeling of [things being] chaotic or haphazard. I’ve been in other environments where there’s a lot of high expectation and pressure – I don’t know if it’s male energy, but maybe, where there’s a feeling of ‘This better f***ing be good or else’. And it doesn’t work very well or even if it does it just feels so hard. But with Doll it’s the opposite, it’s almost like she’ll be amazed if it is good! And yet it’s brilliant!”

She then reaches for an unexpected comparison. “Doll will love this but I am going to compare her to Martin Scorsese – I can’t believe it – but in both cases it was the same. I felt really noticed and looked at and cared about. It sounds so name-droppy, but I’ve done two Scorsese films, and he makes you feel seen, too. With really good directors they somehow help you understand the world of their movie, and you can then do anything and you can go anywhere. You just get it.”

Mortimer and Wells last worked together on the comic satire Doll & Em, a biting TV series in which they played outsized versions of themselves. It was incredibly funny, peppered with cameos from the likes of Susan Sarandon, John Cusack and the pair’s real husbands and mothers, but it was also subtly dark – speaking to the paranoia and isolation fostered on film sets, and how actors so often mask feelings of loneliness and self-doubt beneath a camera-ready veneer. Mortimer says she has always struggled with it.

“You disguise it with all of this camaraderie, and all this ‘dahling, dahling’, but I think most actors are a little bit lonely in one way or another,” she says. “Most people are, probably. But maybe actors just feel it more keenly or are more aware of it and do more to compensate for it. Or maybe they’re more lonely because they’re more peculiar.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

She connects her own personal self-doubt with her childhood. Cripplingly shy back then, to the extent that she never wanted anyone to come to her home out of fear they’d “think it was weird and that I was weird”, she battled with insecurities and the shame of wanting to act.

“I didn’t think of it as a serious profession,” she explains. “I remember dancing in front of the mirror with my hairbrush and pretending to be Debbie Harry and that to me was [just] showing off. That wasn’t serious, that was just trying to be cool or wanting people to think I was amazing, rather than a serious business of like, interpreting some play and bringing stories to audiences. That definitely wasn’t my driving impetus at the beginning. It was more like, ‘Oh, I really like pretending to be Blondie in front of the mirror, I’d really like to be a film star or something.’”

Burying her face in her hands out of embarrassment, she recalls throwing on a vintage hat at age eight or nine and reclining by her family’s swimming pool eating oranges and pretending to read War & Peace – “like I was some sort of 1950s bathing beauty”.

“I always felt slightly ashamed of these weird little things that I was doing because it seemed like a slightly dirty secret,” she says. “But now I look back on it with more forgiveness. It was like creating a world in my imagination where I could escape from this person I was in real life.”

She says she’s “nicer” to herself today, joking that such a thing is a necessity as you get older “because no one else is going to be”. But it turns out that losing her chronic feelings of embarrassment only happened in the most forceful way possible, and via some very public nudity. In Nicole Holofcener’s wonderful 2001 indie dramedy Lovely & Amazing, Mortimer’s character is forced to strip naked for her cruel lover, who proceeds to inspect her body from top to bottom and tell her what needs improving. She says the scene forever transformed her.

“A lot of actors, and especially people who went to drama school, always talked about ‘being in the moment’,” she explains, “and I was always like, ‘Oh my god, I don’t think I’ve ever been in the moment! What does that mean? I’ve never been to drama school, I’m a fraud!’ And then she wrote this scene, and I was madly in the moment. There was never less of a gap between me and the character I was playing – I was as vulnerable, as brave, as stupid, as naked, as everything. It was an incredible feeling and I felt like, ‘Oh, this is proper, and I’d like to keep doing this.’”

She pauses, before holding up her hands as if she doesn’t want to get too ahead of herself. “I mean, I’ve still been embarrassed about myself a lot since then,” she laughs. “But that was the beginning of starting to think – you know what, maybe there’s something cool here?”

In person, candid and prone to genuine laughter, you could never tell that Mortimer once struggled so much with her profession and other people’s perceptions of her. But then there are moments in which her old self seems to creep through, particularly in her terror about coming across as too dramatic or actor-y. “Oh god, you’ve got to be careful not to make me sound too pretentious,” she begs at one point.

Mortimer has lived in the US since 2000, having met her American husband, the actor Alessandro Nivola, on the set of Kenneth Branagh’s Love’s Labour’s Lost a year earlier. But she admits that she never thought it would be such a permanent move, or that US acting work would so readily flow in. While visiting Nivola in Los Angeles in 1999, Mortimer was put up for a few innocuous auditions by her agent. Intended as a mere sampling of the true “actor-in-LA” experience, they ended up producing actual jobs, with Mortimer unexpectedly winning the role of a doomed, fame-hungry actor in Wes Craven’s Scream 3.

“It was a bit like a bizarre joke that I was in this thing,” she recalls with a laugh. “But it was amazing, you’d just be constantly running down corridors with a person with a dagger chasing you. You should pay people for that kind of therapy.” She also came to love Craven, who died in 2015. “I still feel sad talking about him, because he was a real advocate of mine. He was such a sensitive and bright and lovely man. So I really feel affection for that movie.”

After Scream 3 came a Disney comedy with Bruce Willis, she and Nivola got hitched, there were roles in The Pink Panther, Lars and the Real Girl and Cars 2, and somehow the US stuck. She says Nivola was the main reason why she went to America, but admits that “in an incredibly subconscious way” there was something about the United States that also offered a blank slate. Mortimer wasn’t a household name prior to her move overseas, but she was somewhat known as the presumably very privileged and Oxford-educated daughter of a very famous man – the young girl-about-town with a column about acting in The Telegraph and a cameo as Hugh Grant’s far-too-perfect blind date in Notting Hill. It may have been charmed, but it was still baggage.

“I was just really allergic to the idea of being one thing,” she says, “I suffer from the same disease that we all suffer from [in England] which is that the minute you meet someone, you’re trying to understand where they went to school, who their parents are, or where they were brought up. It’s an occupational hazard of being English. I didn’t like being told who I was because I had gone to a certain school or because I had a certain father – there’s something about being in America where that just isn’t interesting to people.”

“I definitely feel, and felt, always incredibly connected to here and feel so torn about being there.” That’s changing, though. “Now it’s like – ‘Okay, I give up. I love this man and I’m in this place and I’m just happy that I’m alive.’”

Good Posture is released on 4 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks