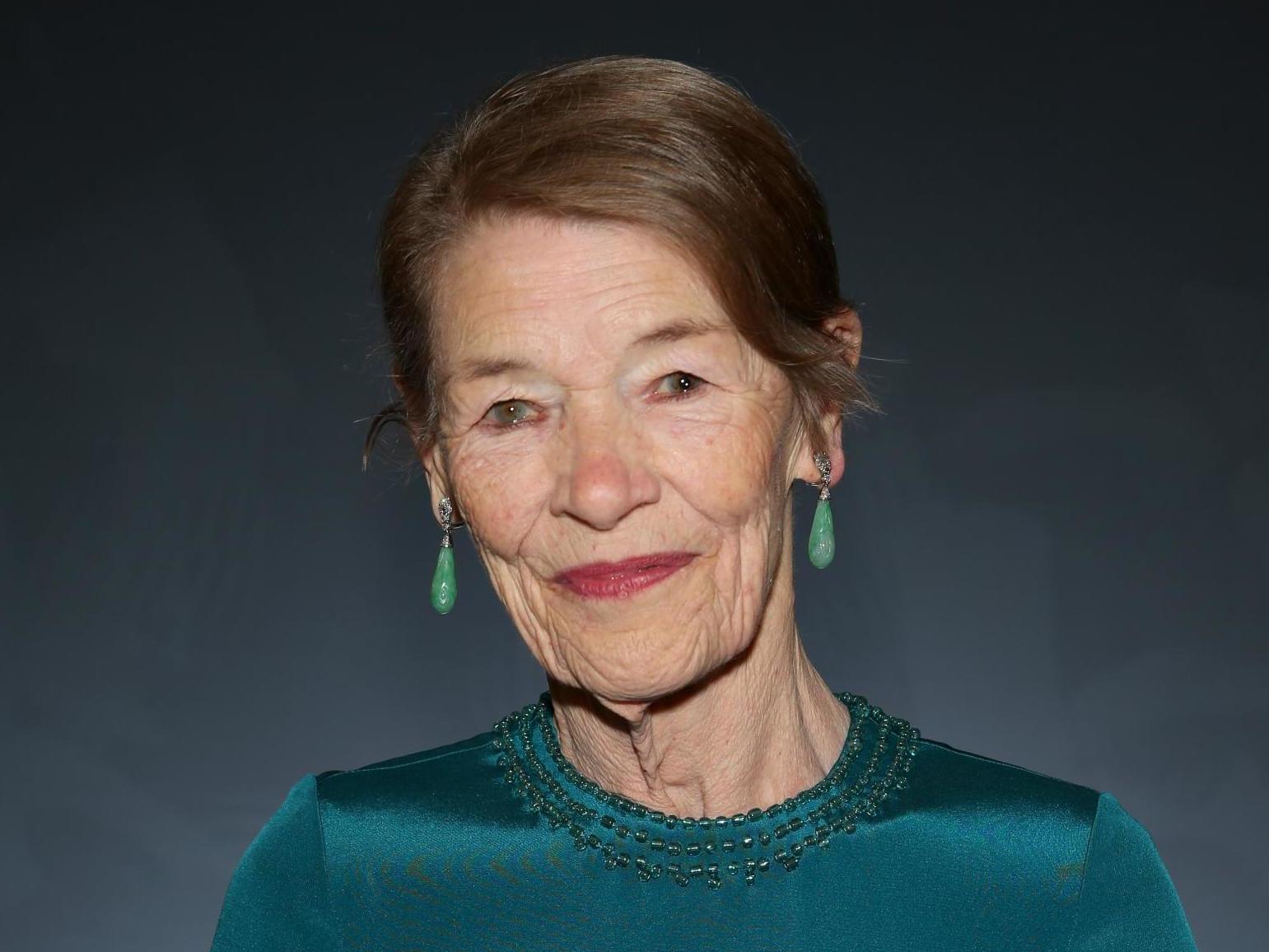

Glenda Jackson: ‘My family’s anxious every time I sneeze’

The Oscar winner and former politician – who was awarded a Bafta on Friday night for her role as a woman losing herself to Alzheimer’s in ‘Elizabeth Is Missing’ – talks to Chris Harvey about her first on-screen part in 27 years and why she doesn’t want to be asked about ‘women writers’

There’s a fascinating 1976 interview with Glenda Jackson on YouTube, at the end of which the double Oscar-winning star of Women in Love (1971) and A Touch of Class (1973) and future Labour MP is asked by the male interviewer if she is “waving a flag for women’s lib”. Jackson, who has answered everything up to that point with striking articulacy and frankness, fixes her gaze on him, burning cigarette in hand. “Waving it?” she replies, with a crocodile smile. “I’ll poke it in your eye if I have to.”

I have this encounter in mind when I talk to the actor on the phone about her return to acting on the small screen after 27 years. Jackson is 84 now, and, God, it’s good to have her back. She simply becomes the central character in the BBC One drama Elizabeth Is Missing, which aired in December, and can be streamed on Acorn TV. For her performance as a woman gradually losing her independence to Alzheimer’s, who’s gripped by a fear that something has happened to her friend, she is awarded, as was widely expected, a Bafta for Leading Actress. It is her first television Bafta, although she won a film one for John Schlesinger’s Sunday, Bloody Sunday in 1972, and has been nominated for several others. She already has two Emmys, a Tony and a Golden Globe.

She’s “surprised” to be nominated, she says, and “grateful”. The role, though, had her asking herself if Maud’s struggle against dementia had become her own. “Oh yes, there were days when I thought I was on my way down. Certainly.” But, she adds, “it’s always hard to know what is your experience and what is the hangover from playing the character”.

She hasn’t been outside the front door of her basement flat in south London since the lockdown began, she tells me, although she has been gardening a lot. Does being in a vulnerable age group for Covid-19 make her anxious? “It certainly made my family anxious,” she says. “Every time I sneeze or cough, everybody looks at me as though, ‘Oh God, have you got it?’ All I’ve got is a bad leg, which is driving me crazy.” She lives in the same large house as her son, the Mail on Sunday columnist Dan Hodges, his wife and her grandson. Do she and Dan ever argue about politics? “Yes, we do, and we’re both implacable.” Does she agree with his contention that the liberal left despise the white working class? “No, I don’t.”

Jackson, of course, is working class herself. She spent two years cleaning shelves behind the medicine counter in Boots before joining an amateur dramatics group and winning a place at Rada in the mid-Fifties. She notes that from her experience, the working classes are quite conservative. In 1992, she gave up her stellar acting career to become an MP for the Labour Party. She served under a succession of leaders beginning with Neil Kinnock and ending with Ed Miliband, but most notably under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown during the party’s 13 years in power from 1997 to 2010. She was a thorn in Blair’s side, a vocal opponent of the Iraq War, and of tuition fees, as well as a hardworking constituency MP in north London. And yet… And yet she’s a once-or-twice-in-a-generation actor. Did she ever have moments on the back benches, when she thought, ‘What am I doing here? I should be on stage or in front of a camera’?

“Well I’ve never regarded myself in that light,” she says, briskly, “[but] no, never, I mean it’s an extraordinary privilege to be a member of parliament.”

Sometimes she did step into the spotlight, famously delivering a speech to howls of protests when the House of Commons was recalled to mark the passing of Margaret Thatcher in 2013. “Everything I had been taught to regard as a vice,” she declared, “was, in fact, under Thatcherism, a virtue: greed, selfishness, no care for the weaker, sharp elbows, sharp knees, all these were the way forward.” That day, she railed against the state of hospitals in the country. “I tremble to think,” she said, “what the death rate among pensioners would have been this winter if that version of Thatcherism had been fully up and running this year.”

She agrees that her fears about provisions for social care have been fully realised during the coronavirus outbreak – “absolutely” – but refuses to blame the government for the shocking number of deaths in care homes. “No, that’s going too far, because many of the people who have died in care homes have other diseases.”

She decided not to stand at the 2015 election. Six months later, she surprised everyone by returning to acting, at 79, in a radio adaptation of Emile Zola’s Rougon-Macquart novels, and one year later, she was back on stage, as Lear in a gender-blind King Lear at the Old Vic. “A terrible fierceness of spirit animates the slight, rather frail figure this Lear cuts…” wrote Paul Taylor in The Independent. “That metal-tipped whiplash of a voice is undimmed in its power to inflict devastating, incredulous scorn.” She later reprised this monumental feat on Broadway.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

It has often been suggested that Shakespeare’s Lear is suffering from dementia, and I want to know if there is any of Jackson’s Lear in her Maud in Elizabeth Is Missing. But she disagrees with that premise: “He has a mental breakdown, but he does come out of it.”

Had acting changed while she was away – did she have to alter how she performed? “No, not at all, no,” she says vehemently, although she later conjures an amusing image of a vanished British acting world when we’re talking about her first Hollywood film, A Touch of Class. She reportedly got the part after the director saw her on The Morecambe and Wise Show. The film’s risqué-for-the-time plot features a divorced woman (Jackson) who agrees to an affair with a married man (George Segal), because she could do with “some good healthy, uninvolved sex”. Does she think it prefigured the Tinder era? She doesn’t. “The big thing about that was working with an American actor. I mean, I’d been raised in the theatre, where British actors would go, ‘Oh God, OK,’ put down The Times and do a bit of rehearsing. Here was a guy [for whom] it was life and death.”

She once described acting as “a mysterious process which no one can actually define or teach”. She tries to explain to me “the difference between performing and doing it” – by which she means, I think, being the character. “You have to see the world through their eyes. Unpleasant as that may be for you.”

There’s a moment in the drama when Maud unleashes a terrifying silent scream in a restaurant. Jackson’s face conveys so much torment without words. It’s something I’ve seen her do before, using her face to tell you everything about her character’s inner state. In Ken Russell’s The Music Lovers (1971), in which she plays the nymphomaniac wife of Richard Chamberlain’s Tchaikovsky, the camera finds her at one of his performances, her features rapt with excitement and desire, even as his gaze focuses on an attractive man in the audience. “I wish I could detail for you the path that I go down, but I can’t,” she says.

Russell shot a wild, alcohol-driven love scene with Jackson in that film, at a time when full nudity was very rare. “Yes, suddenly the set would be enormously crowded,” she recalls. Does she think films are more exploitative these days? “No, I don’t think so… I think there was a time where [nudity] was undoubtedly an exploitative thing, but I think we’ve moved on from that now.”

After so long away, she watched the #MeToo movement happen from inside the industry. Were there things that she remembered happening in her career that would be considered sexual harassment now? “No,” she says, but she was “astounded” when the industry responded with a collective “‘Oh gosh, we never knew this.’ Of course everybody knew that kind of thing went on. I found that bizarre.”

What of some of the other hot-button issues that have come up since she has returned. Does she feel that trans men or trans women should be played by trans actors, for instance, or that anyone should be able to play anyone? “I do rather,” she says. “I think in many ways it’s a fallacy to think that we know ourselves so well, that we’re the only people who can play ourselves, whatever that may be… to think that only a transgender actor would know what it is to be [transgender]. Does that mean that only murderers can play the Scottish play, or things like that, you know, how far down the road do we go with that? It seems to me to be the antithesis of what we should all be looking for, which is, we’re basically all human beings, or we hope we are.”

There’s a line in a film she shot in 1975 with Michael Caine, The Romantic Englishwoman, directed by Joseph Losey, with a script by Tom Stoppard, in which her character declares, “Women are an occupied country.” Is that still the case? “I think there have been movements, slight movements, that have begun the process to genuine equality. But essentially underneath everything that has happened and is happening, there’s still this rider around all women: if a woman is successful, she’s deemed to be the exception that proves the rule. If she fails, well, that’s just par for the course. And I can’t see that that has shifted, essentially.”

![Jackson in 1970: ‘I think there was a time where [nudity] was undoubtedly an exploitative thing, but I think we’ve moved on from that now’](https://static.independent.co.uk/s3fs-public/thumbnails/image/2020/07/29/16/gettyimages-856894148.jpg)

“When you think that a woman in parliament,” – she pauses – “it didn’t happen to me but it still happens… there’ll be stories about what she’s wearing, like Theresa May and her leather trousers. Come on, get a grip,” she growls.

Is she happy with Keir Starmer? “Oh very much so. I’m very surprised that he’s come up to the plate as quickly as he has.” Does she think that this government has made mistakes in handling the pandemic? “Are you kidding me?” she replies, picking out the delay in enforcing mask-wearing in shops as an example. “Where are the grown-ups, for God’s sake?”

I raise a point made by many that the inner decision-making cabal of Boris Johnson’s government – believed to be Johnson, Dominic Cummings and Michael Gove – would have benefited from having women involved in key decisions rather than being exclusively male. “Well, there are no surprises there, are there?” she says, scornfully. But would it have helped? “Well that’s rather countered by whether you support Johnson or not [inside the party]. And that doesn’t seem to me to be an even split between male and female. I mean, there are women who are only too happy to work with him. Shame on them is my view, but there you go.”

I bring up an issue that must have a particular resonance for Jackson – the rise in domestic violence that has occurred during lockdown. In 1999, in an interview with The New Statesman, she said: “I don’t think I’ve ever been in a relationship with a man in which he hasn’t raised his fists to me.” How upsetting does she find the reported 20 per cent increase? “I wish I could say it surprised me, but it didn’t,” she says. “When I was a girl, what happened behind your front door stayed behind your front door. We have moved on beyond that… but of course it’s going to happen, and we have to take the steps to begin to eradicate it rather more energetically than we have done in the past, because it’s not only women who suffer from this, the children in that situation suffer from it as well.”

The campaigning politician is still very close to the surface. I wonder if she’s been catching up with theatre and TV since she retired from politics. “I wouldn’t say I’ve been catching up on theatre much,” she says, “partly because I was doing it a lot. I’m a big radio fan, actually, although I do watch the telly.”

Jackson falls into the age bracket that will no longer be exempt from the BBC licence fee now the rules are changing. I ask her if she thinks that the corporation should be forcing over-75s to pay? “I’m in two minds over this. I think in essence, it should be the responsibility of the government – but they’re not going to step up to that particular plate. I’m one of the beneficiaries of it at the moment. I suppose if I was pushed I would say, ‘Well, I paid my taxes for a damn sight longer than I don’t have to pay for the telly…’ but equally what is important to me is that the BBC should survive and if that is the only way it can survive, then the BBC must stay in place.”

The corporation, of course, is under threat from the streaming giants, Netflix and Amazon. I note that barely any of the complex late Sixties and Seventies work in which Jackson appeared – such as the Watergate satire Nasty Habits (1977) or her portrayal of the poet Stevie Smith in Stevie (1978) – is available on them. She mentions that she still gets letters from Europe – especially Germany – when her films are shown there.

Does she think that cinema and theatre can recover from the pandemic? “Oh, yes, but it won’t happen overnight.” At least, she says, the creative industries can rely on imagination to help them overcome the situation.

I want to ask her if there are any of the great women writers who have come through over the past decade that she’d particularly like to work with: I mention Lucy Prebble, Phoebe Waller-Bridge, Michaela Coel. Finally, a ticking off arrives.

“I’m happy to work with anybody if the script is good,” she says. “I think it’s great that they are coming through. I still find it irritating that you just said, these ‘women writers’. Women have been writing both in the theatre and outside the theatre for a very, very long time.”

Admonishment accepted. Almost made it…

Elizabeth Is Missing is available to stream now on Acorn TV

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks