Loving Vincent: How the world’s first fully-painted feature film took six years to make

The animated film of Vincent van Gogh’s final days in which his portraits come alive meant living Vincent for its painters

If the word “unique” is overused, particularly when it comes to film journalism, it can genuinely be applied to Loving Vincent. An immersive animated portrait of Vincent van Gogh, the film is set a year after his 1890 death as Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth) – a one-time sitter for the artist – reluctantly peers into the mysterious circumstances surrounding his demise. Was it suicide from a self-inflicted gunshot wound? Or something more sinister? Like an amateur sleuth, Roulin talks to those that knew the Dutch painter, many of whom featured in his work.

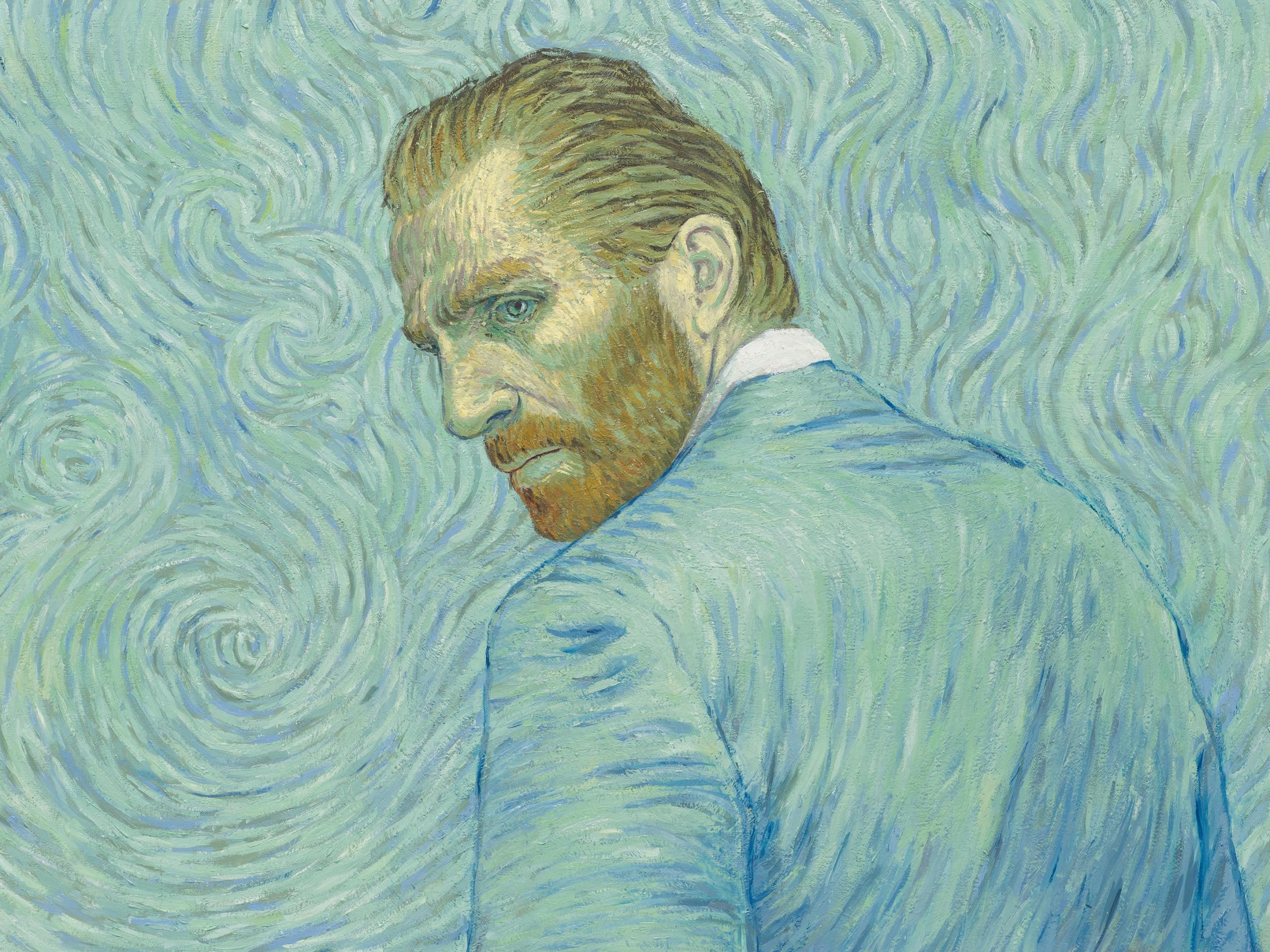

Yet it’s not this period detective yarn that makes Loving Vincent unique. Using 130 of Van Gogh’s paintings, sewn together tapestry-like to form the film’s backdrops, it’s an ever-morphing canvas that shimmers in front of your eyes. “The directors didn’t want to make up Van Gogh paintings,” says Booth, the young British actor from The Riot Club. “They wanted it so all the action happens in the paintings that he painted.” Imagine Starry Night or The Night Cafe come alive; it’s every bit as revolutionary and remarkable as watching, say, your first Pixar movie.

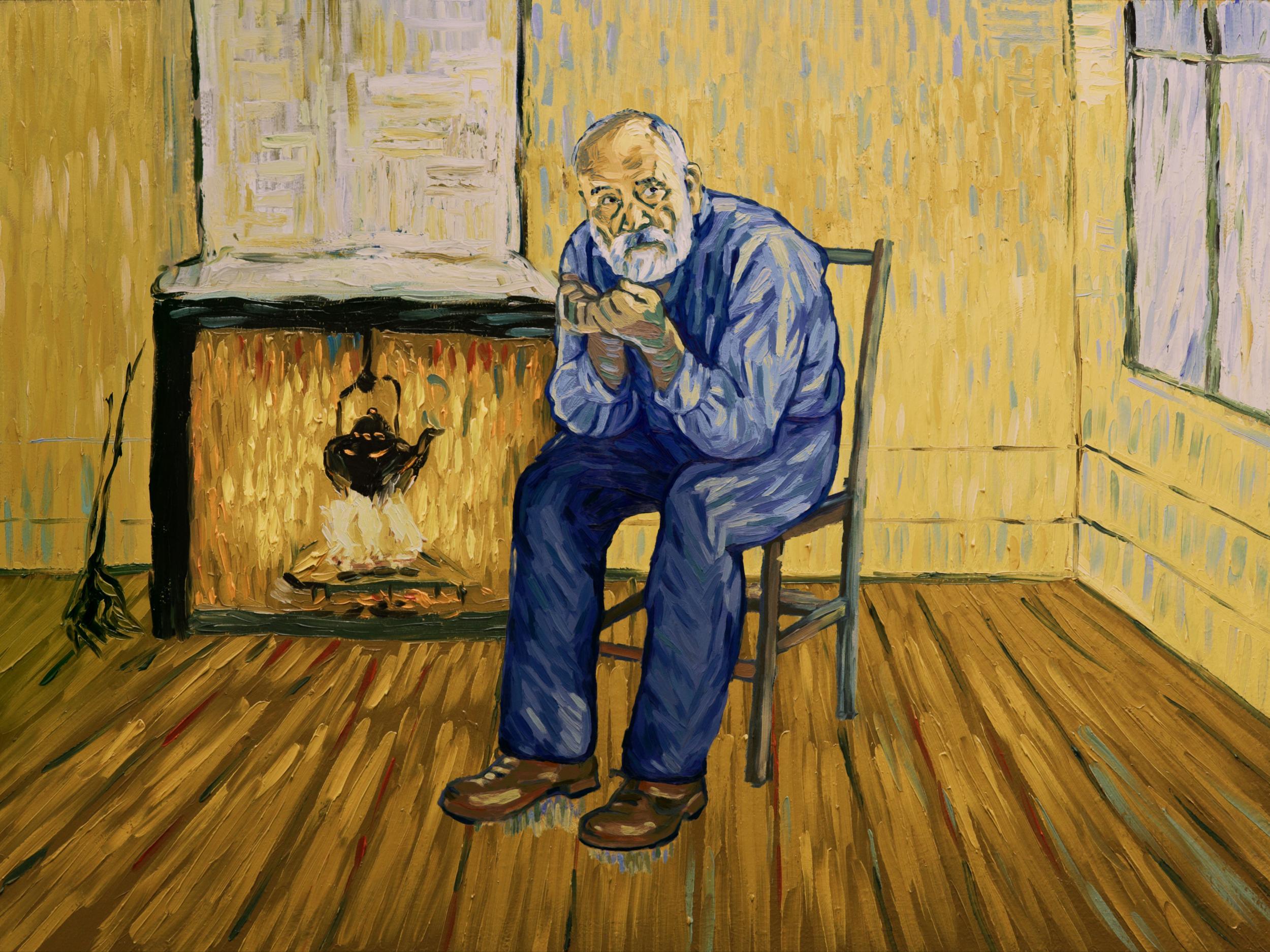

The co-directors in question are British animator Hugh Welchman and his Polish-born wife Dorota Kobiela, a trained painter who first envisaged making an animated short using paint as her source material. After she met and married Welchman – the founder of the Oscar-winning BreakThru Films – they decided to tackle the idea as a full-length piece. Thus, the world’s first fully-painted feature film was born. In essence, the idea was simple: an artist would render a full oil-on-canvas image. “That could take between half a day and three days,” says Welchman, “and then for twelve times for every second [of the film], you’re moving the paint.”

What this means in practical terms is nothing short of painstaking. For a character, say, who may be turning their head, the head and maybe shoulders will be scraped off the main painting and redrawn – twelve different times per second to simulate movement. Compare that to the relatively simple task of re-modelling a piece of clay, as seen in stop-motion animation, and you begin to understand the mammoth task faced. To give it some numbers, 65,000 individual frames were painted, with 125 artists beavering away across a production that took six years from beginning to end.

Simulating Van Gogh’s instantly recognisable brushstrokes was also crucial. “It’s a real dedication,” says Booth. “They spent hours and hours in the Van Gogh museum studying the application of the paint, the drying times, the texture.” The actor shot his scenes two years ago, on rudimentary sets; the basic footage was then used by the artists. “They projected every single frame onto a canvas and then they painted over that frame,” explains Booth. “The artists didn’t just come in and trace everything. What they had to do was interpret Vincent’s style. So you almost feel the texture of the paint. It’s so alive.”

Using hundreds of letters written by the painter as a basis for the story, Welchman and Kobiela always felt Van Gogh’s unconfirmed last days was where their focus should lie. “Once we decided to bring his paintings to life to tell his story, then we were bringing to life portraits of people who knew him in his final years,” says Welchman. “And it turned out that many of these people had conflicting views of him. So it felt more natural for them to be talking about him immediately after his death, because that tends to have the most impact on a group of friends.”

The real challenge was to present a different side to Van Gogh, beyond the suffering artist who struggled with his sanity, famously cut off his ear and died in relative obscurity, at the age of 37. “The thing that was dramatic for me,” notes Welchman, “was that in his last year, even his last seven months, he’d just started to get the kind of recognition that could give him hope. He’d sold his first painting for a decent sum of money. His work was finally being appreciated by the painters around him, like Toulouse Lautrec, Monet, Gaugin… it was obvious that he was going to succeed. It was a matter of time. It just seems so tragic.”

While Van Gogh is played by Robert Gulaczyk, he’s largely kept in the shadows, glimpsed in black-and-white flashbacks as others recollect him. Unlike Robert Altman’s Vincent and Theo or the classic Kirk Douglas-starring Lust For Life, this isn’t a straight-up biographical presentation of a man descending into madness. “We really wanted to go away from how do you portray Vincent’s particular craziness,” says Welchman, “and more concentrate on being in a world full of his words and full of his paintings.”

Booth concurs. “Sometimes you lose the artist in a biopic of the artist. This was telling his story through his art. I felt more connected to his vision and the way he saw things by the end of this film, than if you didn’t include his artwork.” Like Welchman, the actor was no expert on Van Gogh when he started, beyond knowing that he first picked up a paintbrush at 28 and then spent eight furious years creating. “I went on a similar journey to my character in that I discovered more about who he is as an artist and as a man,” he says.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

So far, says Welchman, reaction from Van Gogh scholars has been positive. “It was a nerve-wracking day for me when I showed it to the two senior researchers at the [Amsterdam-based] Van Gogh museum,” he notes. “It felt a little bit like going back to school.” The script carefully does not posit wild theories. “We only ever fictionalised the gaps.” Even with a character like Roulin, the filmmakers worked initially with what they had. “We know Armand was a blacksmith in his late teens and later in life he became a detective… a gendarme in Algeria.”

Coupled with a beautiful score by Clint Mansell, Loving Vincent, as the title suggest, is a true labour of love, a passionate paean to the post-impressionist. “I would love for him to be around to see what a loving tribute that has been made to him,” says Booth. “The amount of love and affection that people have for him and his work.” What does he think Van Gogh would’ve made of seeing his paintings come alive? “He’d probably think he was on acid! A hallucinogenic dream… what did he say? I dream and then I paint my dreams. You can imagine him dreaming in this format.”

‘Loving Vincent’ opens in cinemas on 13 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks