Marilyn Monroe was a remarkable actor – so why are we only fixated on her death?

A new Netflix documentary gives the Hollywood bombshell the true crime treatment, and it is an icky, unsettling watch. And when Monroe’s demise is already covered more extensively than her actual acting, do we really need another opportunity to gawp, asks Adam White

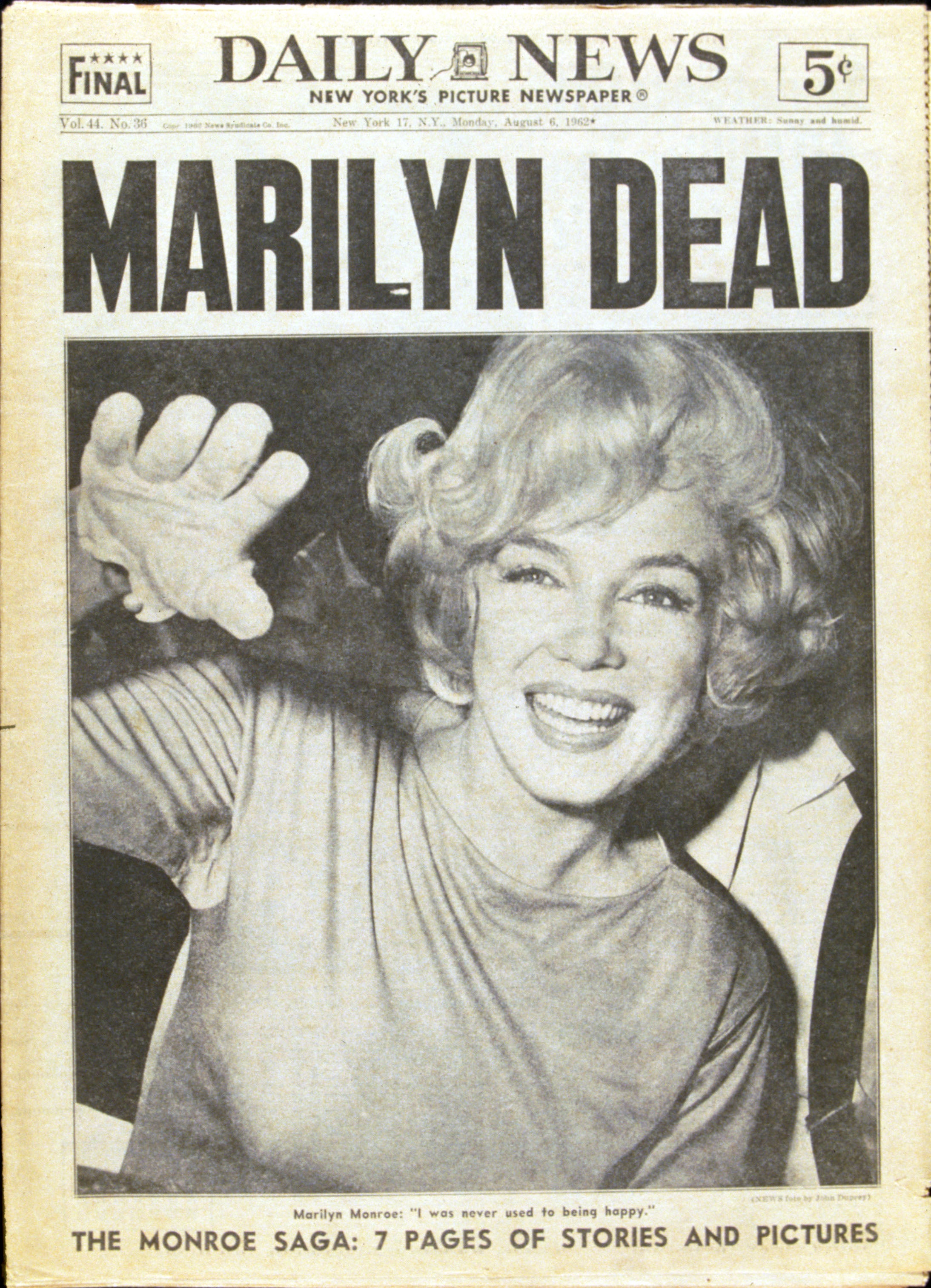

Marilyn Monroe looks her saddest in slow motion. More and more, that tends to be the only way we see her. Perhaps it’s because it’s so much easier to scan her face for melancholy when archive footage is played at a snail’s pace, whether she’s walking down a city street or posing for photographers. Her smile becomes steely, or frozen in hidden anguish. Every downward glance makes her seem briefly bereft. If Monroe today was an Instagram filter, it’d be named “beautiful depressive”.

This image is none more apparent than in Netflix’s The Mystery of Marilyn Monroe: The Unheard Tapes, which can be streamed from today (27 April). The film angles Hollywood’s eternal icon through the lens of a true crime documentary, with author Anthony Sommers – who wrote the bestselling Monroe biography Goddess – examining previously unpublished claims regarding her final hours. Nothing gets confirmed, making the whole thing a bit aimless, but there are allusions to Monroe’s affairs with both President John F Kennedy and his brother Robert – which may have put her in fatal government crosshairs – as well as claims she was being investigated and monitored by the FBI due to her leftist politics. Interview tapes from a 1982 investigation into Monroe’s apparent suicide are also heard for the first time, with friends and associates sharing – or deliberately not sharing, in some cases – what they knew about her demise.

Monroe died 60 years ago this August, which explains the abundance of material being released about her this year. That includes the much-delayed biopic Blonde, starring Ana de Armas, which has been described as unconventional in its approach and so provocative that it’s been given an adults-only NC-17 certificate in the US. A French documentary is also due for release this June, one that boasts of having “finally” identified Monroe’s biological father.

Our cultural fascination with Monroe bears no explanation. She is, after all, the prototype of all kinds of modern media phenomena, from the mystery and allure of the “dead blonde” in popular entertainment (see Twin Peaks or any of the television formed in its image), to the hyperfixation with young women struggling in the spotlight. “Missing White Woman Syndrome”, or a kind of discrimination in which missing persons or victims of crime are granted comparatively larger news coverage when they’re young, white, female and pretty, feels somewhat indebted to her, too. Monroe probably wasn’t the first example of any of the above, but she is their collective blueprint, someone whose talent and beauty is so often tied up with her private turmoil.

Watching The Mystery of Marilyn Monroe, though, I felt icky. It is but the latest in a long, long line of documentaries, feature films and books about Monroe’s life and career, and isn’t more or less voyeuristic than any other. Rather, it’s the format that rankles. The doc is part of a specific strand of modern storytelling, of which Netflix is king, where horrid deaths are dissected and speculated over as if they’re stories in soap operas. Visually, there’s the requisite stock footage of murky city streets and ominous tape recorders playing incriminating audio. Dramatic recreations and photographs of dead bodies. The aforementioned slow-motion archive material. There is little difference, narratively or visually, between the Monroe series, Our Father and The John Wayne Gacy Tapes, the latter programmes also revolving around grim historical criminality and both starting in the last seven days on Netflix, too.

There are revelations, however. Elements of Monroe’s personal life unearthed in the new film were ones I didn’t know about. For instance, that she harboured incestuous revenge fantasies about the biological father she never knew. Or that much of her life seemed to be an endless parade of sexual abuse, exploitation and bullying from the men she put so much romantic faith in. Her struggles to conceive a child, and the destructive tendencies that seemed to awaken in her, are discussed casually. But like so many Netflix true crime sagas, the film’s central figure becomes little more than a body, one that we’re invited to know intimately and gynecologically; a prop to ponder about. You feel a bit like a peeping tom at an autopsy.

Of course, it’s a far greater tragedy when these true crime films revolve around dead people who aren’t famous, such as the often forgotten victims of Ted Bundy or Ed Gein. There, the focus tends to be placed on their killers, the people they murdered being solely defined by their ends. Similarly, though, it has become harder to find modern work that celebrates Monroe outside of her demise, the talent she had, or her otherworldly charisma as a movie star. A lazy reading of her appeal will always be that she was more image than substance – a Hollywood bombshell beloved solely because of her looks, whose visage now graces T-shirts and Etsy wall art. Missing from that reading is the raw skill she had as an actor: her loopy guile in Some Like It Hot, the dangerous allure she brought to the underrated noir Niagara, or the piercing loneliness of her work in The Misfits, her final film.

In fairness to The Mystery of Marilyn Monroe, we do get clips of many of her most famous roles, as well as testimonies that speak to her artistic genius and the work she put into her performances. “Every night, she would go to her [acting] coach,” her Gentlemen Prefer Blondes co-star and friend Jane Russell says at one point. “She wanted to be good. And when the camera went on, it was like a whole electric light went on. She just came to life.”

But these moments feel present by genre necessity, a bit of context tossed in at the start before the conspiracies begin. As of writing, none of Monroe’s actual films can be streamed on Netflix UK, making The Mystery of Marilyn Monroe potentially the first – and maybe only – port of call for audiences looking to discover her. What a shame. And what a missed opportunity.

‘The Mystery of Marilyn Monroe: The Unheard Tapes’ is streaming now on Netflix

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks