‘This is the right time for Snowpiercer’: Tilda Swinton and Ed Harris on the botched release of the dystopian classic

Bong Joon-ho’s 2014 sleeper hit had a botched release thanks to producer Harvey Weinstein, but it’s out now on Blu-ray. Clarisse Loughrey speaks to its stars

One of this year’s few, precious joys was South Korean director Bong Joon-ho achieving what many thought was impossible. His film Parasite won the Academy Award for Best Picture, showing that Hollywood can indeed be coaxed out of its subtitle phobia. Its success, both during awards season and at the box office, also felt like a redress for the mistreatment of his first English language feature, 2014’s Snowpiercer. It had all the right ingredients for Stateside success: frenzied action, larger-than-life characters, and A-list names like Chris Evans, John Hurt, Tilda Swinton and Ed Harris.

But it fell foul of Harvey Weinstein, who acquired the distribution rights, demanded his own cut and – when Bong stood firm – retaliated by limiting its US theatrical release and pulling the UK one altogether. It deserved a much better fate than it received but, after first turning up on Amazon Prime and Netflix, it’s finally coming to the UK in Blu-ray form, in conjunction with a new TV adaptation streaming on Netflix, starring Jennifer Connelly and Daveed Diggs.

An explosive attack on capitalism, Snowpiecer is set in a future where the Earth has become a frozen wasteland and its last survivors are now cloistered together on an enormous train, divided on strict class principles. As it circles the globe in a perpetual loop, revolution brews within, as the tail-sectioners rise up to take the engine. Although Snowpiercer bristles with rage in the face of inequality, it hides a gentle heart. It possesses great imagination, a deep social conscience and a radical spirit.

Tilda Swinton stars as Minister Mason, the train’s second in command. “However frustrating the delay has been for us,” Swinton tells me, “this release is simply the result we always looked forward to: the right time for our film. No doubt, Parasite will have gathered countless new admirers to Bong’s work, so Snowpiercer can be the beneficiary of this new following,” Swinton adds. Her Snowpiercer co-star, Ed Harris, who plays the train’s mysterious architect, agrees. “I was thrilled and extremely happy that people were realising the creative genius of director Bong.”

The story behind Snowpiercer is both long and intermittently vexing. It begins in a bookshop near Seoul’s Hongik University in 2005, where Bong stumbled across Le Transperceneige, a French graphic novel by Jacques Lob and Jean-Marc Rochette. He stood there and read the whole thing in one go. By the time he got home, he’d decided it would be his next project. Starting with the basic concept of a post-apocalyptic locomotive carrying the world’s population, he added his own details: the revolt, the slimy protein blocks used to feed tail-sectioners, and the ideological system that hails the train’s driver, Harris’s Wilford, as a prophetic saviour type.

Bong wrote the screenplay, enlisting Kelly Masterson (behind Sidney Lumet’s final film Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead), to help with the film’s English dialogue. And, in late 2012, both the script and a test reel were shown to Weinstein. He was thrilled – The Weinstein Company acquired the film’s distribution rights for North America, the UK, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, and the director ended up with a fairly sizeable $40m budget. But the producer did not like what he received in return. Bong loves to tell a particular story about his interactions with Weinstein. One scene in the film sees the tail-sectioners confronted by Wilford’s enforcers – all leather-clad, balaclava-shrouded thugs. None of their masks have eyeholes, so they blur into a single, soulless block of authoritarian intimidation. Before they strike, one of them brings out a dead fish and gently dips his hatchet into its flesh. He passes it around. Soon, each of their weapons is trimmed with luminous, red blood. It’s a ghastly image, a premonition of this group’s casual brutality. But Weinstein wanted it gone. Bong retorted: this moment was a personal tribute to his father, a fisherman. “He replied, ‘Oh, why didn’t you say that before? Family is the most important thing. We must not cut this out,” the director recalled at a recent BFI event. There’s one addendum here. The story? “It was f***ing lies.” His father’s a graphic designer.

Weinstein wanted to cut around 25 minutes from the final film – living up to his nickname, “Harvey Scissorhands”. Any moment too strange or gruesome was targeted. He demanded an explanatory voiceover, too, and suggested fantasy writer Neil Gaiman for the job. Bong asked Masterson to cook something up instead. In the end, both the Weinstein-approved edit and the director’s cut were screened for test audiences, on opposite sides of the US. It was Bong who emerged victorious. His version received much higher test scores and the producer eventually relented.

But Weinstein, never gracious in defeat, insisted that the film only receive a limited theatrical release in the US before being dumped on video on demand. It earned a healthy $10.5m there, though it had already grossed $80m in other territories. The critics were won over by its originality. The New York Times praised its “refreshing” and “playfully postmodern” take on the post-apocalyptic genre, while The Guardian described it as “if Terry Gilliam or Michel Gondry had been hired to rewrite Samuel Beckett”. If it had received a proper release, there’s no doubt it would have been a major hit. According to Bong, “perhaps for him that was a punishment, but for us it was a happy ending”. After The Weinstein Company filed for bankruptcy in February 2018 (Weinstein has since been found guilty of sexual assault and rape and is currently serving 23 years in prison), several of its films were picked up by rival distribution companies. Lionsgate is behind the new UK Blu-ray release; Swinton is also confident that “one day, soonest” UK audiences will be able to see the film on the big screen.

Now, at least, Parasite fans can better appreciate what Bong achieved with Snowpiercer. The films intertwine, tonally and thematically. Both used confined spaces – a train or a luxurious home – to create microcosms based around class and capitalism. And, as Bong himself has pointed out, both dramatise a revolt of the lower classes expressed through a movement across that space. In Parasite, the Kim family rise up from their dark, musty basement apartment and take residence in the palatial Park home. In Snowpiercer, the revolution pushes from one carriage to another, from the back to the front. One is vertical, the other horizontal.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

It’s a world we see through the eyes of Curtis (Chris Evans), the uprising’s de facto leader. Each new carriage feels like stepping into a different universe. His home, the tail end, is a maze of steel, wires and misery. People’s belongings clutter the rows of bunk beds, forming cramped alleyways. He travels through the service quarters – with its stark, plain walls and elegant greenhouses – and on to the hedonistic indulgence of the front carriages. There are fur-swathed orgies and Orient Express teatime fantasies. The idea that all these places can exist in such close proximity to each other won’t surprise anyone who’s seen first-hand the effects of gentrification.

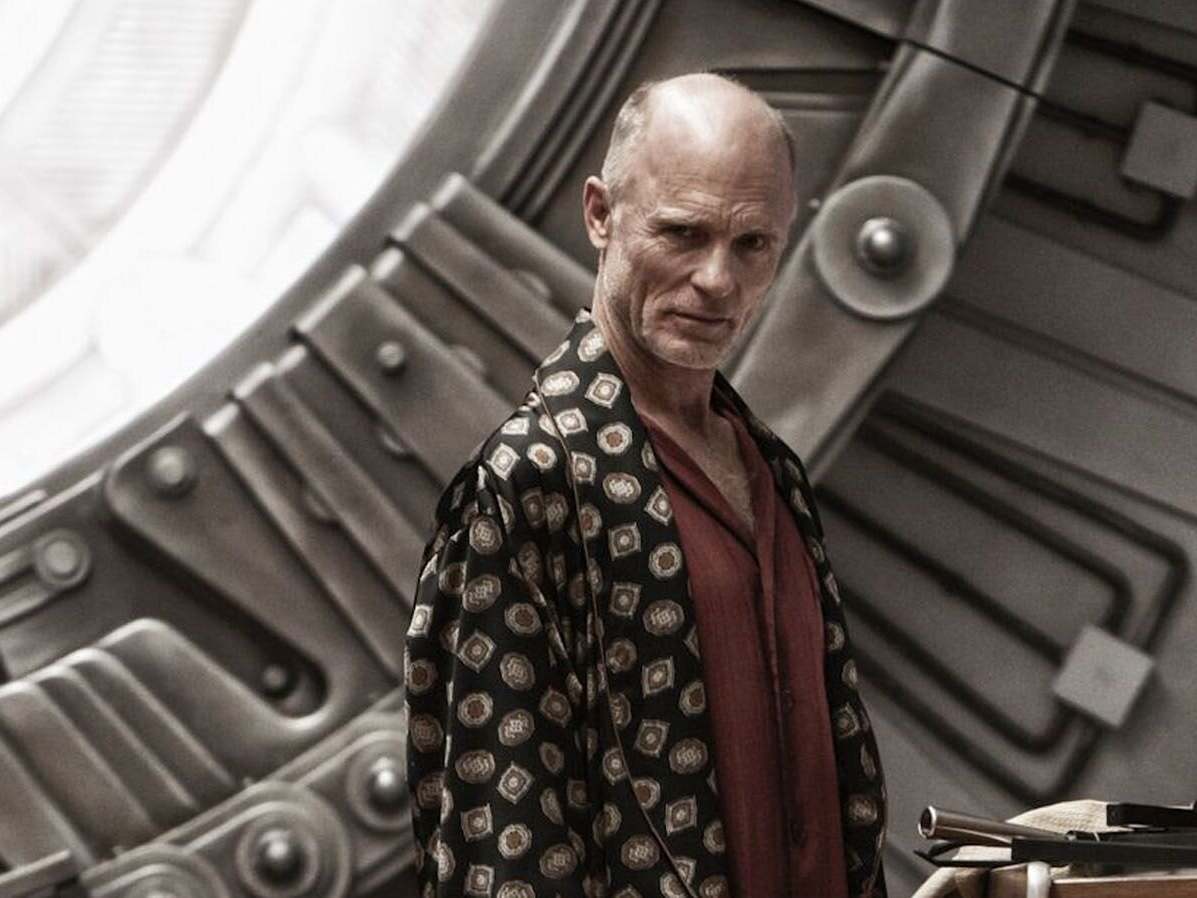

Bong has created a world that feels totally complete. “When I was led through the cars leading to Wilford’s ‘haven’ at the head of the train,” Harris notes, “the detail and imagination that had gone into the creation of this world made me realise a lot of my work had already been done. Wilford’s world was there. All I had to do was inhabit it.” Curtis is shaped by his environment – the hardship he suffered has shouldered him with unspeakable guilt, which Evans carries right in the angry furrow of his brow. The actor flipped his virtuous image as Captain America on its head, then smashed it into pieces. Wilford, meanwhile, embodies the front of the train. His silk pyjamas suggest both wealth and complacency. “When I met with [costume designer] Catherine George and she showed me what she had in mind for Wilford’s wardrobe, his insouciance regarding the unfortunates at the rear of the train and his confidence in the rightness of this endeavour became even more obvious,” Harris says. The actor was the last to be cast. His familiar, gravelly voice bounces off the walls of the engine room, bringing a sudden sense of calm within all the fury. Wilford possesses the charisma of a cult leader and the mystique of an otherworldly sage.

And the engines he tends to? It’s capitalism itself, condensed into the whirring of a few cogs and wheels. “If we control the engine, we control the world,” Curtis says. “Without that, we have nothing.” It is both a machine and an idea, fanatically upheld by Mason. She’s a ghastly caricature of the human form, with her piggy nose, prominent teeth, itchy wig, and fake war medals. The script refers to Mason as “Sir” and Bong had initially considered John C Reilly for the role. But Swinton and the director had met at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival and bonded instantly. He went ahead and offered her the role.

Mason is the clownish authoritarian we recognise both today and in our history. “We wanted to create a grotesque, a melding of the most baroque bombast of all the political monsters we could think of: Hitler, Mussolini, Gaddafi, Thatcher, Berlusconi,” Swinton told Dazed in 2017. Her inherent ridiculousness protects her and humbles her in the eyes of those she wields authority over. Yet Mason isn’t a source of power. She’s merely a walking loudspeaker. Bong has hinted in the past that she may have started out as a tail-sectioner and climbed the ranks. It’s why she’s the most enthusiastic disciple of them all – she’s aware her privileged position is a fragile one.

The lie told to every individual on this train is that they’re perpetually indebted to the system. “You people, who if not for the benevolent Wilford would’ve frozen solid 18 years ago today,” Mason tells the tail-sectioners. “You people, who would suck on the generous titty of Wilford.” Her words are echoed by the folk tales of the doomed “Revolt of the Seven”, recounted by the train’s equally hysterical teacher (Alison Pill). But Snowpiercer is radical not just because it dares satirise our fervent dedication to capitalism, but because it asks the tough question: can a better world be found by taking control of the system, or must it be dispensed with entirely? As Curtis discovers, there is a deep rot at its centre. As long as the engine exists, there will always be a front of the train and a back of it. It’s the most unexpected of people who comes up with the solution: Namgoong Minsoo (Song Kang-ho, Bong’s frequent collaborator), a man everyone has so far dismissed as nothing but a wreck and a drug addict.

Snowpiercer effortlessly tucks potent political thought into the thrills of an action-driven fantasy – there is terror, blood, humour and humanity. “All cinema is built on fantasy and imagination,” Swinton says. “What Bong understands so beautifully is that this freedom is something any audience not only craves, but has an unlimited capacity to go for: he can push the hardest bargain with our ability to follow his switchback ride from the mundane to the hilarious to the operatic to the horrific to the blatantly political and round again.” Bong’s vision – whether it’s at its most heightened in Snowpiercer or The Host, or more restrained in Parasite – feels all the more urgent now that capitalism has been left at its most exposed, both by the pandemic and the slow creep of climate change.

In Snowpiercer, we’re told humanity created its own doom: the release of CW-7, intended to control global warming, plummets the Earth into a second ice age. “Clearly, in the last seven years, the urgency of the realities of a climate emergency of our own making and the patently insupportable toxicity of global capitalism have become even more – ever more – undeniable for all but a minority of, what one may describe as, deeply challenged individuals,” Swinton says. “But, for many of us, the writing has been distinctly on the wall for, frankly, a couple of centuries.”

Bong’s never been interested in minor details or specific points in time. He’s a big-picture director – who sees our world as it is and ever was. And he paints these ideas on canvases that teem with life. In Swinton’s words, the brilliance of Bong is thus: “His faith in cinema, his understanding of its inexhaustible capacity to transport, engage, amuse, inspire and transform. His absolute belief that it is his party and he’ll do whatever he damn well pleases. His compassion, his wit, his boldness, his grace. Head, heart, hand: his Bongness.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks