Spotlight: Oscars Best Picture winner tells the story of The Boston Globe's finest moment

The film is a faithful re-telling of the investigation that in 2002 blew open a Catholic paedophile scandal involving scores of priests in Boston. David Usborne travels there to meet its real-life heroes

Alexa MacPherson struggles at first to say why she has kept so many copies of one issue of The Boston Globe in a box in her attic all this time, her eyes turning a little misty. They are all dated 6 January 2002 and all bought from the same newsagent around the corner from her parents' house, where she grew up.

The answer is obvious. But if she is floored for a second, it's because of the sheer weight of it. Finally, she offers a single word: "Freedom." It was the day, she remembers, when she finally regained it, when the institution that had caused her so much suffering was rendered naked; when all those things she had been trying as an adult to tell anyone who would listen – there weren't many – were shown to be true.

And it was the day that the things that she might have said as a child, but could not, were also laid bare. No, it was not that one time the priest had tried to rape her on the family couch and when her father had walked in and found him. It had been countless times before that, over five years, from when she was four-and-a-half. And it hadn't just been her. The same priest had repeatedly abused two of her brothers, too.

Nor was there confusion any longer about all the times she had gone to her mother as a child and asked for her help because her "pee-pee hurt and was red and sore and blistered", and her mother hadn't sent her to the doctor or asked any questions but instead had put her in the bath and "rubbed on a stupid pink goop called Comfortine" every time, thinking the problem would go away, like an infection.

One morning last week, in the office of her lawyer, Mitchell Garabedian, Ms MacPherson, who is now 41 and has two children of her own, pushes across the table a small, faded photograph of herself aged about five or six. It wasn't, of course, this smiling little girl with blond curls who had harboured an infection. It was the priest who had raped her and the Catholic Church in Boston, which had employed and protected him.

Those copies of the Globe marked the start of a torrent of articles over the following months about the Catholic Archdiocese, the sexual abuse committed by its clergy and the lengths gone to by its hierarchy to cover it up and keep the media at bay. They were all written, at least initially, by members of a tiny team for special investigative projects called Spotlight, originally formed at the Globe in the 1970s on the model of the Insight investigative unit at The Sunday Times. It is still going today.

The series on clergy abuse blew open a scandal that was to consume the Church worldwide for a decade and still does today. It earned the team a Pulitzer Prize in 2003. The framed citation hangs with the scores of others awarded to the newspaper over the decades on the wall of a second-floor landing in its handsome headquarters in Dorchester, on the southern fringe of the city. (They will be moving soon to a new, less expansive home in downtown Boston.) But few achievements of the newspaper were as big as this one. And now a new, rather different sort of accolade has been paid to it, by Hollywood.

Spotlight is a journalistic "procedural" that, as faithfully as possible, follows the paper's reporters and editors as they embark on their mission to fathom how far the clergy-sexual-abuse contagion had spread and find the evidence to prove it. And it opens in Britain burdened with some pretty lofty expectations. Critics in the USA have swooned over it. Directed by Tom McCarthy and with a script by Josh Singer, it has been showered with six Oscar nominations, including for Best Picture.

"This was so unexpected, you know, we never thought the movie would ever even be made," says Ben Bradlee Jnr, the deputy managing editor at the Globe at the time, with responsibility for the Spotlight unit. He has since retired to write books. "We thought we'd had our great reward with the Pulitzer."

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

It has not escaped Bradlee, played in the film by John Slattery, that the result is surely the most widely watched film on the reporting business since All the President's Men, in 1976, about the pursuit of the Watergate conspirators by The Washington Post – when his father, Ben Bradlee Snr, was that paper's editor. (His celluloid self was Jason Robards.) "There are certainly similarities. Watergate and this were both local stories which had national and in our case international implications," he adds.

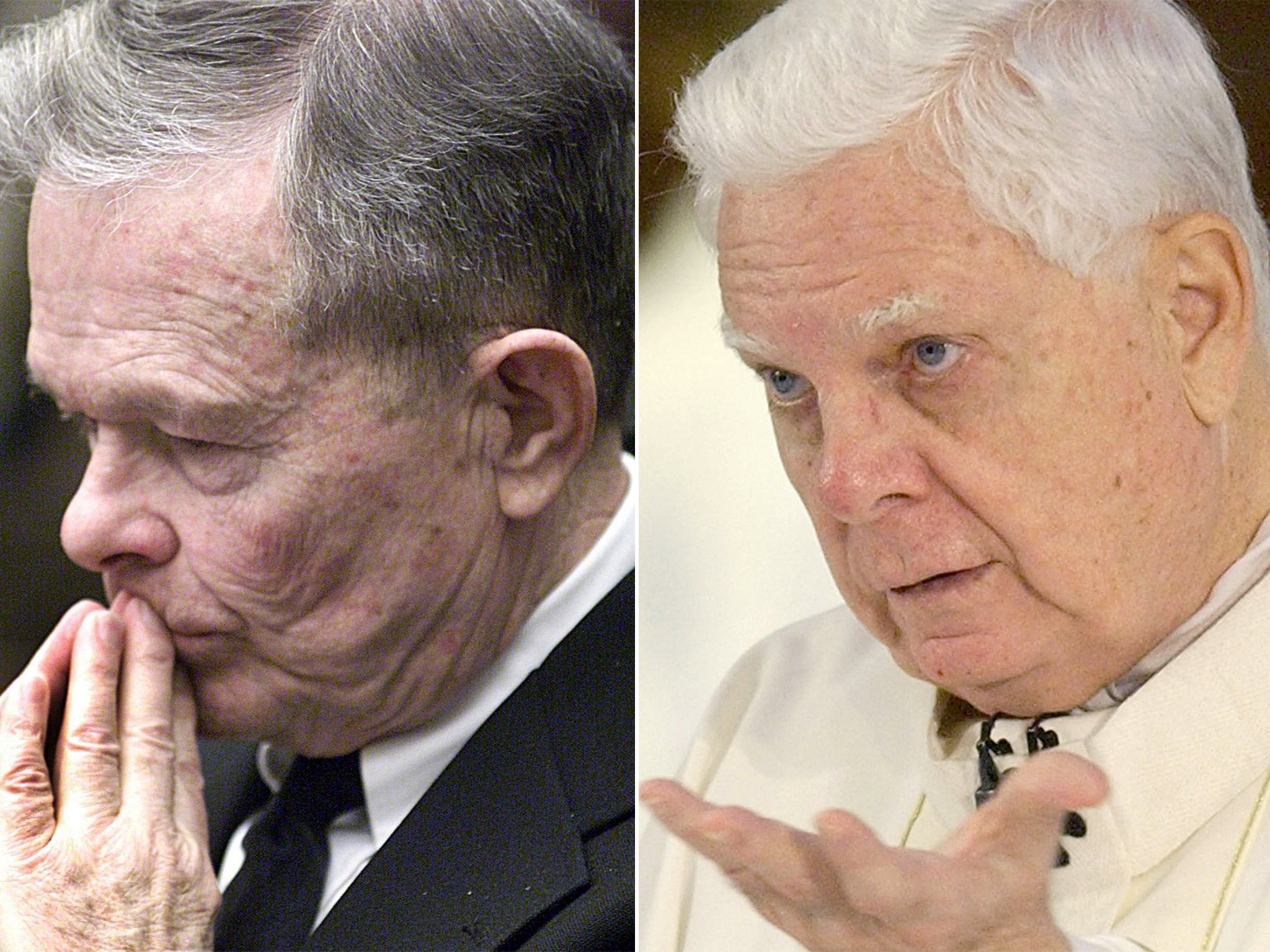

The Church story might not have been broken at all but for the arrival as editor-in-chief at the Globe of Marty Baron (who, as it happens, now edits the Post). Not from Boston and not a Catholic, he summoned both Bradlee and the newly installed Spotlight editor, Walter Robinson (played in the film by Michael Keaton), and asked that the unit drop whatever it was doing and start investigating whether instances of paedophilia – linked to one already-defrocked priest, John Geoghan – might extend further. Neither man was keen, initially.

"It wasn't our cup of tea, but I went down and told my troops and said, 'This is my new boss and the new boss gets what he wants,'" Robinson recalls. "We dove into it with a vengeance. We just started to call everyone we could think of, using the vacuum-cleaner approach. We went back to Marty and told him we hadn't got much on Geoghan but we found out he was the tip of a pretty big iceberg."

It would be five months of hard slog before the first article about clergy abuse was published. Sacha Pfeiffer was one of the four Spotlight reporters at the time and still remembers the early going. "We were curious," she explains, sitting in the cafeteria of the Globe, where she still works (though she left for public radio for a spell before returning). "It was the ultimate reporting challenge. The Church was sort of impenetrable. It didn't have to give us anything. How do you penetrate the impenetrable?"

Even after the investigation had started, it might have hit the buffers, had the reporters not found and recognised the critical value of a little-known litigation lawyer in Boston who, they discovered, had already been pushing at the Church's defences for years on behalf of a growing list of clients who said they had been victims of abuse. He was Mitchell Garabedian. Ms MacPherson was among those clients.

Exactly as the film depicts, Garabedian played hard-to-get with the Globe. "When they showed up, I was wondering if they worked for the Church," he says in his office. "I thought the Globe might be a shill for the Church. Boston is a closed community so I had my suspicions because, let's face it, it takes a village to raise a child and it takes a village to cover up abuse of a child."

But the paper did gain his trust. Garabedian, who has represented victims of sexual abuse for 30 years and still does today, gave them the break that was at the heart of the original investigation and of the narrative that drives the film. He convinced a judge to force the Archdiocese to release its own secret files detailing what it already knew about its abusive priests and the children they had abused.

"Getting the internal Church documents made the story bulletproof," Bradlee recalls. "The Church couldn't say this is media bias or anti-Catholic bias. We had the fucking documents. In fact, they couldn't say anything except, 'Yeah, you've got us.'" In the meantime, through a process of identifying and painstakingly cross-referencing the movements and assignments of priests in Church directories – a process that spans three minutes in the film but took weeks in real life – the team finally saw the full extent of the problem: at least 70 priests implicated in Boston alone. It was, Bradlee admitted, "the story of a lifetime". The Spotlight team finally let go of it in early 2003 and moved on to other topics.

When two producers from the West Coast first approached the reporters in 2008 about possibly making a film about their Church investigation, they were doubtful, even dismissive. And it made them nervous, too. "We were wary of what Hollywood might do to this tale," Bradlee concedes. "There is no sex, there are no explosions. You look at it and ask: how do you make investigative reporting cinematic? How do you deal with sexual abuse, which is such a rough topic?"

"I actually thought it was a very bad idea to have Hollywood have anything to do with your life because all they are going to do is embarrass us," adds Pfeiffer, whose double in the film is Rachel McAdams. It didn't help when Messrs McCarthy and Singer arrived in Boston and started peppering them all with questions about themselves and their lives. "Sometimes this got very personal, like they were going to get into personal life-dramas that [would] embarrass all of us."

The film they made has drawn praise in part because it shows no interest in any of that: no romances, no detonations. Nor does it dwell on the abuse itself, with dramatised flashbacks to priests in people's homes or in their vestries taking advantage of their prey. It simply puts the audience alongside the reporters doing their work. And they are presented as driven, dedicated but also flawed. There is no hard sell of the reporters as heroes. Indeed, the Globe itself takes a knock when the film tells how, years earlier, it had actually published a story about 20 priests who were allegedly committing abuse, which was inexplicably placed deep in its pages and quickly forgotten about, a fact uncovered by the film's own researchers.

"We ran that story in 1993 and it was on an inside page of the Metro section," Robinson tells The Independent. "There was apparently no follow-up on it, and you look back and say: 'Jesus, how did we not see that as a red flag?' But we were still the first paper to break the code on this whole mess."

What took him and his former colleagues aback was the attention to detail paid by the filmmakers and actors. Bradlee says his "knees buckled" when he walked into the Spotlight's office re-created in a Toronto studio, as it was so perfect – even down to the exact same paint colour on the walls and the right pictures of girlfriends on the reporters' desks. And if the film gets all that stuff right, it's also partly because the real-life reporters were involved from the start, reading scripts, helping the actors to understand their own personal tics and mannerisms. When they saw that in one scene Michael Keaton was meant to show up late at night at one of the reporters' flats with pizza and a bottle of Jameson's, they objected. Hollywood thinks reporters drink Jameson's. Really they drink beer. So Keaton brought beer.

Everyone involved sees the film as having an importance beyond its entertainment value. Take Garabedian. Of all the story's protagonists, he was arguably the least co-operative with the filmmakers. (He didn't meet once with Stanley Tucci, who plays him, but spoke with him on the phone.) It matters to him because it amplifies what the Globe series did more than 10 years ago, bringing the issue to a whole new audience and thus, he hopes, leaving new numbers of abuse victims everywhere feeling less lonely and forgotten.

"The movie is not going to change the Church one iota. They don't care," he offers. "But the movie itself empowers victims to come forward, it empowers victims who have already come forward and it must make the world a safer place for children, because it makes the public aware that they have to look out for the children and protect the children." Garabedian reports, sighing as he does so, that scores of new victims have made contact with him in the few weeks since the film's US release. One of them was from Britain.

It's also important for the Globe, which has suffered a tough decade since breaking the story, as has the whole newspaper industry. It's clearly a morale booster for them and really any reporter who watches it. "It's a chance to remind people of the importance of investigative journalism," Pfeiffer offers. "It's increasingly becoming an endangered species. If people don't buy [a] newspaper we won't have the revenue to do that kind of work." Bradlee concurs, adding that the film could help to re-enliven the profession: "We hope it inspires young people to not give up on the trade and get back into it."

Might the film also be a reminder of the importance of old-fashioned print journalism in the new digital universe, where speed and online traffic numbers seem sometimes to trump reporting depth and integrity? In fact, the Spotlight investigation was published at exactly the moment the Globe had also started publishing online. Because of that, the series took off far beyond Boston, giving it a far wider reach – which in turn also meant the reporters began getting tips from victims across the country, even the world. "I believe this was the first major investigative opus of the internet age," Robinson says.

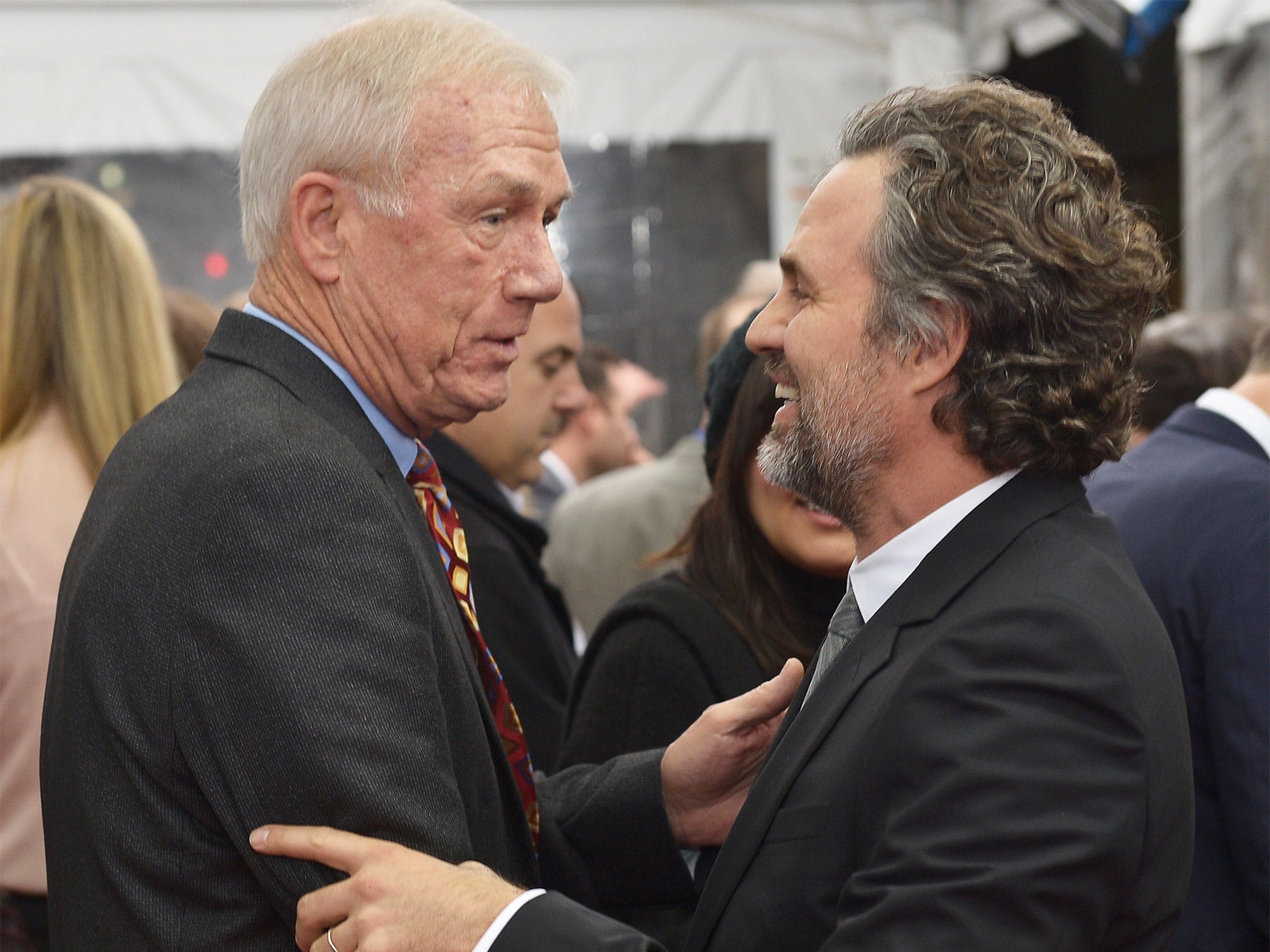

Alexa MacPherson's story is not featured in the film but was written up as part of the series by Spotlight reporter Mike Rezendes, played by Mark Ruffalo. Her file was among those released by a reluctant Church. She remembers her anger reading it. Its sole concern was silencing the priest who had abused her and her brothers and making the case go away. "I thought: 'How dare you? You cared more about the Church and keeping him quiet. You didn't give a damn about a nine-year-old girl.'"

Her lingering fury at the Church – and just a few weeks ago, after seeing the film twice, she blew up all over again at her mother for her baths and pink ointments – is matched only by her enduring gratitude to the Globe. "They gave me triumph over all those people who had told me I was a liar."

The Globe basked in its Pulitzer and is basking again in the glow of the film. But no accolade is more powerful and poignant than MacPherson, one among so many victims, hoarding all those copies of that one issue for so long in a small plastic box in her attic. Because the paper had saved her life.

'Spotlight' is on general UK release from tomorrow

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments