Bronson (18)

Grievous bodily charm

A couple of weekends ago, I found myself drifting through The Shawshank Redemption on television for something like the fourth time: for those few who haven't seen it, it's a film about how an innocent man condemned to a lifetime in prison discovers new reserves of strength and humanity in himself, retaining hope and dignity in the face of brutality, bringing a tiny blast of culture and hope to his fellow inmates, and finally winning freedom. It is not, you'll gather, a realistic picture.

Bronson is The Shawshank Redemption's dark twin, a film in which the hero, a brute himself, never had any hope or dignity to begin with, is guilty as hell, despises culture, and far from winning freedom just coils himself tighter and tighter into the system. It is also not a realistic picture, despite being to all intents and purposes true.

In theory, this is a biography of Michael Peterson, aka "Charles Bronson", who is frequently described as "Britain's most violent prisoner". After being convicted of a relatively petty robbery in 1974, Peterson/Bronson began a career of self-publicising violence, assaulting or taking hostage prison officers and inmates and repeatedly staging protests; as a consequence, his original seven-year sentence has been extended and extended (he's now on a life sentence, though with a possibility of parole very soon). Apart from 68 days in the 1980s he has spent the last 35 years in jail, nearly all of that in solitary confinement.

Prison has provided the setting for plenty of effective films – Cool Hand Luke, The Birdman of Alcatraz, Mean Machine (Burt Reynolds, not Vinnie Jones), Straight Time – not to mention the almost perfect comedy of Porridge; and there are plenty of incidents to keep this one going. So this looks like a promising subject. But Nicholas Winding Refn, the Danish director, and his writer, Brock Norman Brock, seem to have spotted early on that the promise is deceptive: a conventional drama needs not just isolated incidents, but a sense that the incidents are building to something, some development of character; and Bronson doesn't appear to function that way – in his public statements, he hasn't shown any signs of becoming calmer or wiser, of being reconciled to his lot or learning to see the other fellow's point of view.

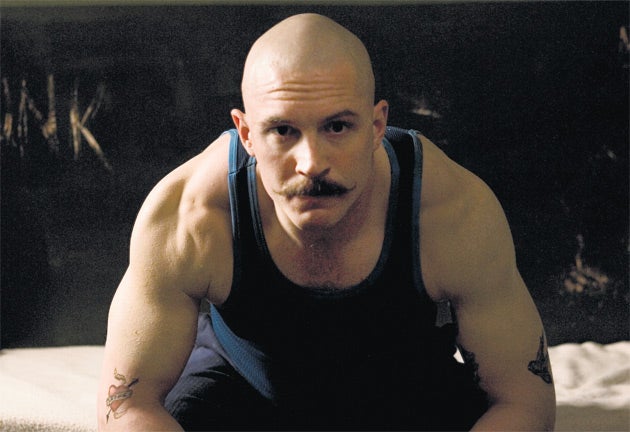

So Refn and Brock have set out to make something less conventional than a biography: Bronson is an opera or a fantasy, a series of tableaux couched about with elaborate rhetorical devices – Charlie Bronson himself (Tom Hardy), standing erect and pop-eyed, Victorian strongman's moustache bristling like quills on an averagely fretful porpentine, as he spouts his side of the story to the camera; Charlie in a music-hall entertainer's three-piece suit – sometimes topped off with clown's white-face – turning his life into gags for an auditorium full of appreciative stuffed shirts. Within this framework, chronology is elusive (and hard to reconcile with the published facts of Bronson's life) and very little looks entirely plausible.

The tone is set by a long, wordless, scene in which prison guards enter a cage where a naked Charlie, body smeared with filth, rages and smashes, and they rage and smash back; it is lit in dim, bloody red and The Walker Brothers are played loudly over the mêlée; there is nothing real or even earthly about all this. The prisons where Charlie is confined are decaying Victorian shells, which seems fair enough, except that they go further, are darker, more crowded, with corridors longer and blanker than the real thing, many of their spaces peculiarly theatrical – Charlie attends art classes at the foot of a stately staircase, meets the governor in a grand arcade.

Some of the movement is very theatrical: pouring tea, Charlie pauses, hands outstretched, briefly a living statue. At one point, he is transferred to a mental hospital where he spends his days tranquillised on a chair in the middle of what appears to be a ballroom, while around him other patients go through rituals of play and dance. The artificiality is enhanced by a soundtrack larded with Verdi, Wagner and Brückner (the largeness and depth of the sound stops it feeling, too, like cheap film-making, though a critical glance suggests that's exactly what it was).

All this is in keeping with Bronson's stylised interventions, with his lavish violence and ludicrous demands (at one point, holding a guard hostage, he demands that music be piped in: I wondered if this was a swipe at the scene in The Shawshank Redemption in which Tim Robbins plays Cosi fan tutte over the prison PA).

The acting rises to fit the style: Hardy gives what ought to be a career-making performance, vast, arbitrary, menacing, comical, but hinting that, beneath all these displays of temperament, lie abysses of absolute blankness; and then, when, during his brief spell outside, the girl he's with explains that she can't marry him, she has a boyfriend, he conveys genuine pathos.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

The supporting cast are given rather less nuanced, extensive parts, but do well with what they have: Matt King as the fellow con who becomes his fight manager and gives him his nom de guerre, louche, self-assured, wafting far above the sordid mess of jail and seemingly unaware how badly he's dressed and how crappy he looks; and James Lance as a camp art-teacher, slipping unwarily into the trap of speaking as if he knows what makes Charlie tick, which is, in Charlie's book, the unforgivable sin.

This is bold film-making – a very pleasant surprise, given that my only previous acquaintance with Refn was a recent duff episode of Marple. But boldness isn't necessarily enough to hold a film together, and there are passages when it all feels a bit too loose, a bit too fancy, a bit too pleased with itself. It's a problem, too, that prison narratives are so ingrained; the film doesn't want to treat Bronson as an existential hero struggling to retain his identity in a dehumanising system, but it keeps drifting in that direction. It's not a masterpiece by any stretch; but it's original and pacy, and those qualities are rare enough.

What did you think of Bronson? Air your views at independent.co.uk/filmforum we'll print the best of them in the newspaper on Wednesday.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks