Film reviews round-up: Hostiles, Brad's Status, Jupiter's Moon, Walk With Me

A striking Western, Ben Stiller’s latest vehicle, the story of a young Syrian refugee, and a Zen documentary

Hostiles (15)

★★★★☆

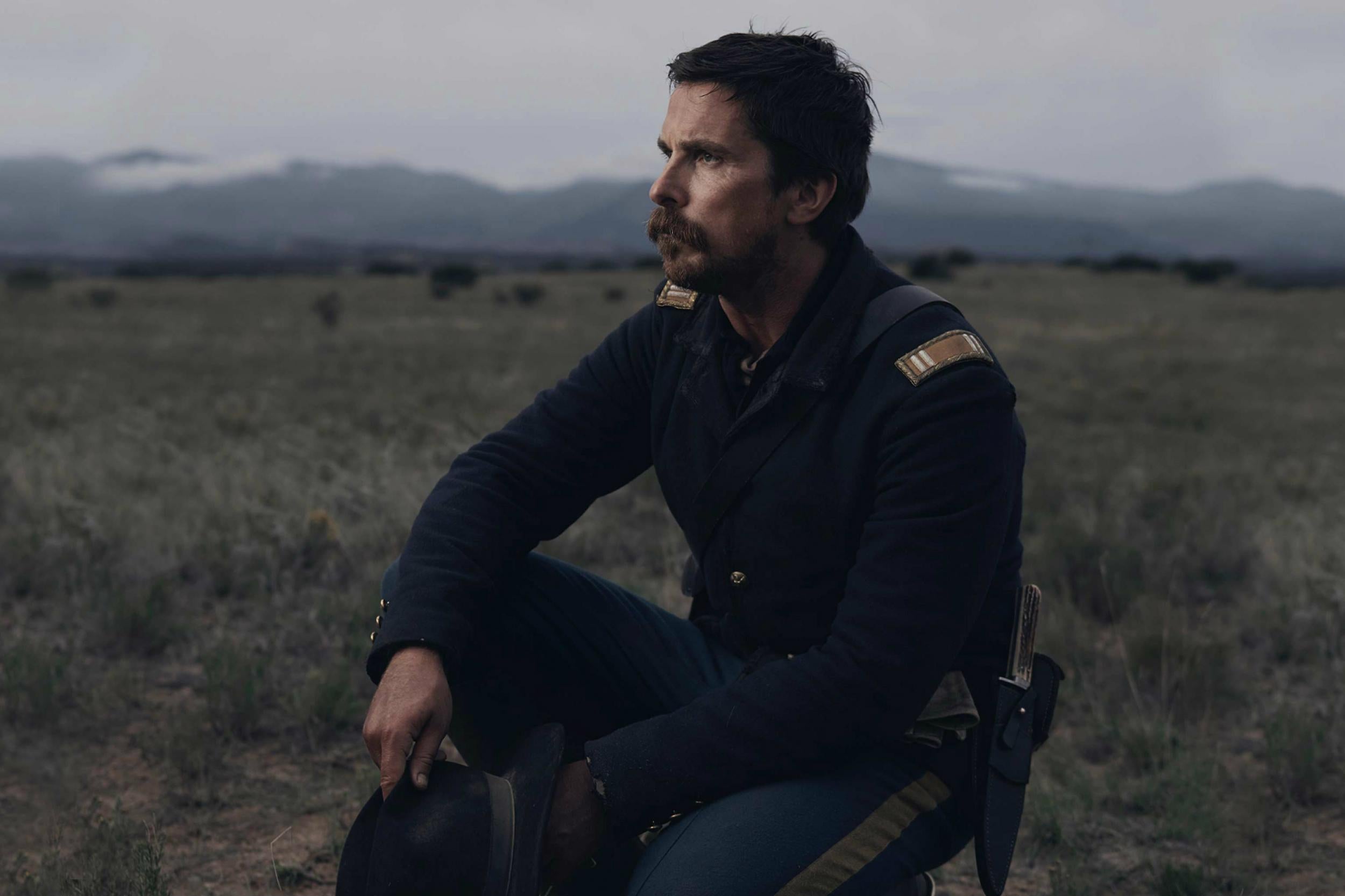

Dir Scott Cooper, 133 mins, starring: Christian Bale, Rosamund Pike, Wes Studi

Westerns don’t come much more brutal than Scott Cooper’s Hostiles. The film has a few moments of Little House On The Prairie-like tranquillity right at the start. We see homesteader Rosalie Quaid (Rosamund Pike) sitting in the parlour, teaching her daughters how to use adverbs as her husband works outdoors, sawing wood.

But then comes the slaughter: the scalping, the shooting, the wanton killing of children. From that point onwards, the tone doesn’t lighten. The Comanches are killers. Their homicidal behaviour is matched by that of the US army. Cooper casts us into a world in which violence and cruelty are endemic and in which men are murdered or tortured in front of their families as a matter of course.

Captain Joe J Blocker is surely the darkest role that Christian Bale has yet tackled. The one-time child actor from Empire Of The Sun is here playing a grizzled, embittered old timer with a hangdog moustache whose hatred of Native Americans puts even that of John Wayne’s vengeful Ethan Edwards in The Searchers to shame.

He’s rumoured to have taken “more scalps that Sitting Bull himself”. He can’t bear to be in a room with “those people”, as he calls his enemies. “I’ve killed savages; I’ve killed plenty of them because that’s my f***ing job,” he hisses.

Blocker is utterly dismayed when his commanding officer orders him to lead a team accompanying cancer-ridden Cheyenne war chief Yellow Hawk (Wes Studi) back to his old hunting grounds in Montana to die.

Yellow Hawk and Blocker provide a twisted reflection of one another. They’re both “butchers”. They’re also men out of time. It’s the 1890s and the old ways are changing. “Civilisation,” as represented by the banks, the politicians, the press and the railroads, is encroaching.

The violence that has distorted both their lives will no longer be tolerated, at least in open view. They can hardly feel nostalgic but the peaceful future looks as bleak to them as the violent past.

To call the mood here elegiac is to understate the matter. The journey shown is like a prolonged death march. At first, Pike’s Rosalie is so traumatised with grief that she becomes delusional but her endurance and will to survive hint at a chance of reconciliation and redemption.

In its own sombre way. Hostiles is very striking. It boasts exceptional performances from Bale and Pike.There is a rugged beauty to its evocation of the Old West. Cooper throws in shots of dawn rising over the plains and plenty of majestic imagery of mountains, forests and deserts. At the same time, it makes for downbeat and forbidding viewing. It’s a film that begins and ends in loss.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Much of the screenplay, which is based on a story written many years ago by Oscar-winning screenwriter Donald E Stewart, is predictable. The filmmakers go to such lengths early on to establish the enmity between Captain Blocker and Chief Yellow Hawk that we know they’ll soon find common ground.

They may be killers but they have their own code of honour. Yellow Hawk is a Cheyenne, not a “rattlesnake” like the Comanches, who kill everyone indiscriminately.

The film can’t make up its mind about human nature. The film suggests that religion and civilisation are no barriers when it comes to killing. Rosalie isn’t coy about emptying the barrels of a revolver into the corpse of a dead Comanche.

Soldiers like Blocker and his old comrade Sergeant Metz (Rory Cochrane) are inured to violence. Metz even gets to deliver a little soliloquy which sounds nearly identical to the one Clint Eastwood uttered in Unforgiven (1992) in which he talked of killing everything that moved, whether man, woman or child. At the same time, all the main characters here are consumed by a sense of longing and regret.

Hostiles is far too traditional to be seen as a revisionist western. Characters are seen framed in doorways, just as in The Searchers. There are echoes of Ford’s cavalry westerns and of his late films like Cheyenne Autumn too.

The explosions of violence rekindle memories of Sam Peckinpah. There is a morose and self-conscious quality to the storytelling that may put some audiences off but the film also stands as a reminded of why westerns continue to be made. If you want to deal with the most primal emotions in the most rugged settings, to combine action and soul-searching, this is still the genre to turn to first.

Brad’s Status (15)

★★★☆☆

Dir Mike White, 102 mins, starring: Ben Stiller, Austin Abrams, Jenna Fischer, Michael Sheen, Jemaine Clement, Luke Wilson

From the ageing Derek Zoolander to the day-dreaming Walter Mitty, Ben Stiller has portrayed his share of angst-ridden, middle-aged nincompoops trying to make sense of their inchoate lives. He gives an appealing performance in a very familiar type of role in writer-director Mike White’s comedy-drama, Brad’s Status.

Stiller plays Brad Sloan, a husband and father living a comfortable middle-class life in the suburbs of Sacramento. He runs a small non-profit company; is happily married to the ever-accommodating Melanie (Jenna Fischer), and they have a talented musician son, Troy (Austin Abrams), who is hoping to go to an Ivy League college.

Brad, though, is prey to extreme status anxiety. “There are moments you realise your entire life’s work is absurd and you have nothing to show for it,” he laments in the voiceover that runs through the film. “There’s no more potential. This is it.” His problem is not so much with what he has failed to achieve as his obsession with the success of his old college friends. They all seem so much more prosperous than he is. For him, the world is a battleground. For them, with their money, girlfriends and private jets, it’s a playground.

When Brad accompanies Troy on a trip east to visit Harvard and Tufts (the colleges his son hope to attend), his paranoia mounts. Little indignities in airport check-in queues or at restaurants eat away at his sense of confidence.

Writer-director White (who also scripted School of Rock) keeps matters light. There are comical fantasy sequences in which Brad imagines the lives his friends are living or day dreams about successes he and his son might yet experience. Brad is neurotic and self-obsessed but Stiller plays him in good natured and comical fashion.

As his exasperated but devoted son, continually being embarrassed by his antics, Austin Abrams is effectively his straight man. There are funny cameos from Luke Wilson and Jemaine Clement as the “friends” whose gilded lives he so envies.

Michael Sheen is excellent value, too, as another of the friends, the preening, narcissistic Harvard professor/media celebrity Craig Fisher, who always gets the best table at restaurants and who, Brad thinks, relentlessly patronises him. Stiller can sometimes be a shrill or over-the-top screen presence. Here, he underplays and is all the more likeable as a result.

The only downside is that the film sometimes feels as superficial as its central character. Brad’s problems, as his son’s friends point out to him, are strictly “first world” ones. He is not really having a mid-life crisis at all. It isn’t so much despair that has engulfed him as a very mild envy and irritation at the lives of others. It goes without saying that he completely misreads those lives anyway.

Jupiter’s Moon (15)

★★★☆☆

Dir Kornél Mundruczó, 129 mins, starring: Merab Ninidze, Zsombor Jéger, György Cserhalmi

The brilliant Hungarian director Kornel Mundruczo’s latest feature sits uncomfortably between political allegory and thriller. It’s the story of a young Syrian refugee who is shot as he crosses the border. Instead of dying of his wounds, Aryan (Zsombor Jeger) develops magical powers – he is suddenly able to levitate at will.

Aryan is taken in hand by Gabor Stern (Merab Ninidz), a sleazy, conscience-torn doctor, still racked with guilt over his part in the death of a young patient. Gabor realises he can make money by showing off Aryan as if the refugee is a novelty act. Both men are being pursued by Lászlo (György Cserhalmi), a gnarled old police office, as relentless in hunting down his quarry as Inspector Javert in Les Miserables.

As in his earlier feature, White God, Mundruczo shows the paranoia and racism in a Hungarian society in which outsiders are regarded with loathing and fear, shunned or treated as potential terrorists.

However, rather than making a conventional political drama, the director turns to magical realism. There are obvious echoes of Wim Wenders’ Wings Of Desire. Aryan is the angel over Budapest, the other-worldly figure often shown up in the clouds, looking down on the city below.

On a formal level, the film is very striking. Aryan will be seen hovering upside down in a hospital ward or gently floating above the traffic and buildings. Mundruczo treats the levitation scenes in a matter-of-fact fashion which makes them all the more startling.

He throws in lengthy travelling shots in which the camera roams through the city as if it shares Aryan’s magical powers. There’s a tremendous car chase late on which unfolds at a ferocious pace but is seemingly filmed in a single shot.

Ninidz’s Gabor is an engaging anti-hero, a crumpled opportunist who turns out to be more courageous and selfless than he first appears. Jeger’s Aryan, meanwhile, is the holy innocent type who doesn’t seem to understand his own powers. Where the film comes unstuck is in its use of hackneyed action movie clichés.

The shoot-outs in hotel lifts and chases through basements and back streets play like scenes out of some low-grade Die Hard rip-off. These scenes seem all the more incongruous next to the meditative and poetic moments when Aryan takes wing.

Walk With Me (PG)

★★☆☆☆

Dir Marc J Francis, Max Pugh, 94 mins, featuring: Thich Nhát Hanh

Walk With Me is a frustrating experience, a woolly minded documentary that doesn’t offer viewers the spiritual relief that its main protagonist, Zen Buddhist master Thich Nhát Hanh, clearly provides to his followers. The master, who left Vietnam in the mid-1960s and was forced into exile in France, is the founder of Plum Village, a rural retreat which (an intertitle tells us) is now one “of the world’s leading mindfulness practice centres”.

Alongside the often exquisite imagery of dawns and dusks or scenes of chanting monks walking through the fields and having their heads shaven, there are recitations on the soundtrack from the teachings of the master. These are read in sonorous fashion by Benedict Cumberbatch.

Directors Marc J Francis and Max Pugh have managed to get very close to their subject. This is an intimate portrait of the Zen master. One of its drawbacks, though, is that it tells us so little about him. The filmmakers’ observational style doesn’t allow space for interviews or voiceovers or for any meaningful contextualisation.

They plunge us into the middle of the retreat. It’s debatable whether watching the master’s followers eating their breakfast in silence or watching them pray and chant takes us any closer to nirvana.

Late on, the filmmakers follow the master and the monks on a trip to the US, where his followers pack out theatres. We see the monks share their teachings at a correctional facility. They tell the inmates they have had to give up money, jobs and sex. Their lifestyle is based around meditation and discipline.

The filmmakers are clearly trying to be as respectful as possible towards their subjects. That means they never ask the simple questions that an investigative journalist might have done. We don’t find out the back stories or even the names of the monks. Nor do we learn how Plum Village is financed.

“At that moment, I felt perfectly at peace. Not one sad or anxious thought entered my mind. Ideas of past, present and future dissolved,” Cumberbatch intones at one stage as we see a shot of a blackened sky with tiny stars in the background. We are told we are at “the luminous threshold of a reality that transcends time, space and action”.

This is all very well but doesn’t make for either gripping or revealing viewing. When it comes to Zen and the art of movie making, Marvel’s Doctor Strange is much more fun than this.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks