Film reviews round-up: The Emoji Movie, England is Mine, Maudie, Williams

Dismal children's fare, a moody Morrissey biopic, heart-tugging folk cinema and an unusual sports documentary

The Emoji Movie (U)

★★☆☆☆

Dir: Tony Leondis, 86 mins, voiced by: Anna Faris, TJ Miller, Sofía Vergara, James Corden

The grimacing face in Edvard Munch's The Scream would be the Emoji of choice if you were looking for a symbol to sum up US critics' response to The Emoji Movie. This new animated feature arrives in the UK trailing behind it some of the most hostile reviews of any film this year. It is certainly very lacklustre fare compared to recent animated features like Inside Out or the latest Despicable Me. Don't expect many smiley expressions among parents forced to take their kids to it.

The case for the defence, which is a very skimpy one, is that The Emoji Movie isn't noticeably that much worse than many other kids' movies released in time for the holidays. It's cookie-cutter entertainment, utterly boxed in by its own ridiculous premise, but given our obsession with our smart phones, you can just about understand why the filmmakers thought it might be a good idea to anthropomorphise the apps.

The film's main character is a young Emoji called Gene (voiced in breathless fashion by TJ Miller.) He lives in the bustling city of Textopolis, which is found inside a mobile phone belonging to teenage boy, Alex. Gene suffers from the same predicament as every almost other character in the movie, namely that he is utterly one-dimensional. His trademark expression, "meh," conveys complete indifference to the world. Gene, needless to say, is curious and enthusiastic. His excitable perspective on life is very different from what his blank face suggests.

When Emojis are ready for work, they sit in squares and wait for their phone user to choose them. Gene's parents, Mel Meh (voiced in ultra-lugubrious, Eeyore-like fashion by ultra-mournful comedian Steven Wright) and Mary Meh (Jennifer Coolidge), don't think he is mature enough to be on the grid. They're proved right when he panics, puts on a silly face and thereby makes Alex think the phone is broken.

Alex plans on taking the phone to the repair centre. If the handset gets wiped, that will mean, whoops apocalypse, that Textopolis itself will be erased. Even if it isn't, the evil Smiler (Maya Rudolph), who has a rictus like grin on her face at all times and is charge of operations at the text control room, will probably have him deleted anyway. Gene therefore embarks on an epic journey across the phone and through its many apps, toward a place where no Emoji has ever gone before, namely the "cloud", where he can be fixed.

Director and co-writer Tony Leondis must surely have realised that he was narrowing down his options by choosing a lead character whose only expression was one of boredom. He manages to generate some comedy from Gene's parents panicking about their missing son - but doing so in such a monotone and low key fashion that they seem as if they're not really bothered at all. Similarly, Smiler keeps on grinning, even when she is at her most fraught and angry.

Gene's travelling companions as he makes his way through app world are Hi-5 (James Corden) and the blue haired, punkish pirate princess Jailbreak (Anna Faris.) The burgeoning romance between Alex and a girl in his class in the outside world is mirrored by that inside the phone, between Jailbreak and Gene.

The Emoji Movie is an example of a movie based on an idea which must have seemed very clever in theory but turns out to be cumbersome and deeply irritating in practise. Leonidis fills the film with as much noise and as many bright colours as possible so we won't notice the shortcomings in its story. There's an excruciating dance-off in one app in which the heroes have to show off their disco moves to survive; a bizarre interlude in the world of Candy Crush, and a quite witty moment when the heroes throw off the bots who are chasing them by making them watch YouTube videos of baby kittens.

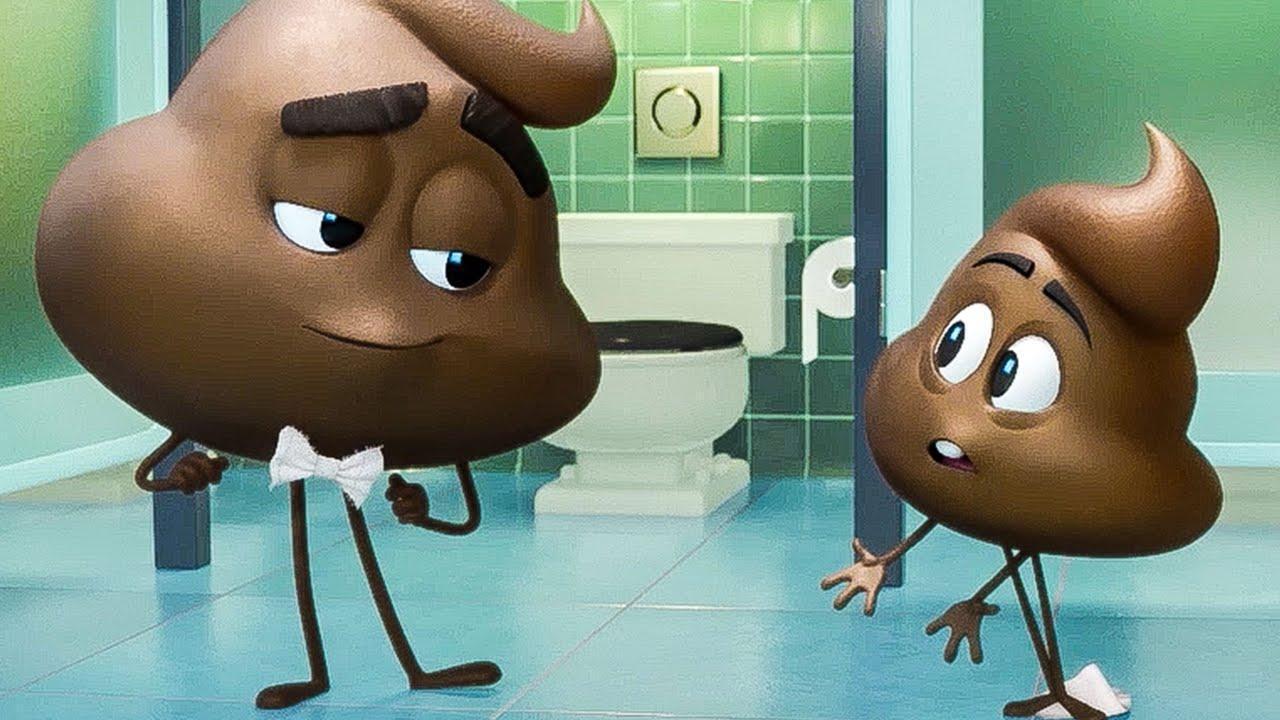

This is a kids' film aimed at a family audience. There is therefore no room for sexting or obscenity. The world it conjures up is oppressively bland. The closest we get to anything remotely subversive is when the poop Emojis snigger and refuse to wash their hands after going to the bathroom.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

The filmmakers would surely have been much better advised to make a movie aimed at teenagers, one that could tap into the sarcasm, cruelty, boastfulness, narcissism and surreal humour that Emojis can be used to convey. As it is, they've served up a story which is far more likely to be greeted with tears, frowns and thumbs-down signs than with smiles and kisses.

England Is Mine (15)

★★★☆☆

Dir: Mark Gill, 94 mins, starring: Jack Lowden, Jessica Brown Findlay, Jodie Comer, Laurie Kynaston

It's when we see the huge close up of his plate of peas, potatoes and baked beans that we realise just how constricted Steven Morrissey's world has become. We all know the character depicted as an awkward young man in Mark Gill's biopic England is Mine will eventually to blossom forth as Morrissey, the singer/songwriter of The Smiths, but as encountered here in his late adolescence and early adulthood in mid-1970s Manchester, he is going precisely nowhere. He lives at home, wears a duffel coat, and has a dead-end clerical job in the tax office. Steven is convinced that he is special and writes pretentious letters to the NME but his social skills are close to non-existent.

In its portrait of the young artist in his formative years, the film has the feel of one of those northern-set kitchen sink dramas that Tony Richardson and Karel Reisz used to make in the early 1960s, with Steven as the latterday Billy Liar. Manchester a little over a decade later is portrayed as dour in the extreme. The sun never shines. Steven is far happier in his bedroom, with his pictures of Bowie and Oscar Wilde, than he is in the outside world. He has vague yearnings to join a band but is far too reticent actually to make contact with anyone. Linda (Jessica Brown Findlay), an art school student with a rebellious streak, helps prise him out of his shell. The visit to Manchester of the Sex Pistols also helps.

Jack Lowden was a dashing RAF pilot in Christopher Nolan's Dunkirk. He made a very credible young Victorian era golfer in Tommy's Honour. Showing his versatility, he now reveals his miserabilist side to fine effect as the young Morrissey. Arguably, he is not as truculent as the real-life version. As played here, Morrissey has an unlikely innocence that stops him from ever becoming entirely obnoxious, even at his most taciturn and self-pitying. At one stage, he laments that he feels like one of those stick-like figures in a Lowry painting, but he's far too vivid a presence for this observation to seem true. His long frizzy hair makes him look more like Marc Bolan than the Morrissey who would eventually become famous.

Gill does an excellent job of recreating what must have been a grim, albeit highly important, period in Morrissey's life. The film is on the dour side. The young man shown here is so awkward and introspective that it's hard to imagine him performing, but when he finally does take to the stage, his charisma is immediately apparent. NME journalist Paul Morley picks up on his talent immediately but his review calls him "Morrison." The promise of instant stardom soon evaporates.

Much of the film unfolds in Morrissey's bedroom. We see him sitting at his typewriter, tapping away. In the throes of depression, he disappears beneath his blankets for weeks at a time. His life appears to be a dead-end. He hasn't made it as a musician. His "attitude stinks." What the film demonstrates, though, is that he is developing all the time, broadening his frame of reference and testing himself out. Just because he doesn't say much doesn't mean he isn't thinking.

Jessica Brown Findlay is by a distance the liveliest character in the film. At times, his relationship with her is akin to that between John Gordon Sinclair and Clare Grogan in Gregory's Girl; in her presence, he becomes wittier and far more confident. They share a love of Oscar Wilde and quote William Blake poems to one another.

If you're expecting Morrissey to launch forth into famous Smiths anthems, to tell us that meat is murder or that we should hang the DJ, or to hear Johnny Marr's swirling guitar work, England Is Mine will prove very anti-climactic. However, as an account of the Adrian Mole-like growing pains of the depressive young would-be artist, the film makes surprisingly poignant viewing. It's cleverly observed and sometimes funny too in its own very downbeat way, as it explains just how Morrissey emerged out of his chrysalis.

Maudie (12A)

★★★★☆

Dir: Aisling Walsh, 116 mins, starring: Ethan Hawke, Sally Hawkins, Kari Matchett, Zachary Bennett, Gabrielle Rose, Billy MacLellan

Maudie is a folksy, heart-tugging and very charming story about a little, arthritic Canadian lady living on the fringes of society who becomes a celebrated artist. Aisling Walsh directs it in the same deceptively simple way that its heroine Maud paints her pictures. The film moves along at a very gentle pace, and there isn't much obvious drama. Walsh appears to be taking her tempo from the mournful, guitar based soundtrack from Michael Timmins (of the Cowboy Junkies.)

British actress Sally Hawkins excels as Maud. She is in almost every scene and her performance has much of the same grace, irrepressible optimism and humour she brought to Mike Leigh's Happy Go Lucky.

There doesn't seem a place for Maud in the 1930s Nova Scotia community in which we first encounter her. Her mother has died. Her money-grubbing brother has sold the family home and she is living a miserable existence with her busybody aunt Ida, who won't let her forget a supposedly shameful episode in her past. Salvation comes in the very unlikely shape of loner, Everett Lewis (Ethan Hawke.) He's a curmudgeonly, taciturn and sometimes violent man who lives in a run-down cottage in the middle of nowhere and ekes out a precarious living selling fish. Harshly treated throughout his life, he regards strangers with extreme suspicion. But Everett wants a cleaner, and Maud puts herself forward for the job.

Maud quickly discovers her place in Everett's household. There's him at the top. Then come the dogs. Next it's his chickens and, finally, it is her. He treats her abominably. Yet she slowly makes herself indispensable to him and brings out a caring side he didn't even know he had.

Maud also loves to paint; she draws birds and flowers on the walls. Her work is noticed by Sandra (Keri Matchett), a sophisticated New Yorker who has a holiday house nearby. Soon, her pictures begin to sell and her fame spreads so far that even politician Richard Nixon buys some of her work.

There has long been folk music and folk art. Maudie is an example of folk cinema. Early on, its self-consciously naive storytelling style seems a little arch. It's strange to see an actor like Hawke, who so often plays romantic leads, cast as a Steptoe-like outsider. Sometimes, as the filmmakers show Maud hobbling down the road, you just wish she'd get a move on. But Maudie quickly wins us over. Director Walsh knows just how to balance the comedy and the pathos as she takes us through her subject's life and chronicles her unlikely emergence as an artist.

Williams (15)

★★★★☆

Dir: Morgan Matthews, 109 mins, featuring: Frank Williams

Sports documentaries tend to be very predictable. Morgan Matthews' Formula 1 film Williams surprises us by coming at its subject matter from an unlikely perspective. Its ostensible subject is RAF bomber pilot's son Frank Williams, the now wheelchair-bound car fanatic who built the Williams team. From modest beginnings and after several unsuccessful years, the team went on to win nine constructors' championships.

Williams himself broke his neck in a car crash in the French countryside in 1986. He came very close to death but returned to the sport and oversaw the greatest years in the history of his team. In a more conventional documentary, this would be all that would be needed for the familiar, rousing story of triumph against the odds. Instead, Matthews concentrates as much on Williams' family as on the race team owner himself.

At the heart of the film is Williams' wife, Virginia ("Ginny"), who died in 2013. She was from an upper middle-class English background and had no apparent interest in cars at all - but was as important to the success of the Williams cars as her husband. Matthews has unearthed audiotapes of interviews Ginny gave for her book, A Different Kind Of Life, about living with Frank. She is utterly honest and unflinching in her account of her marriage. There is even some awkwardly framed film footage of her, sitting on a sofa at home and talking about Frank. She stuck by him when he was on his prolonged losing streak early in their marriage and had no money whatsoever; she advised him on which drivers to recruit, and she saved his life after his crash by nursing him full-time at a point when his doctors were convinced he was going to die.

Another key presence in the film is his daughter, Claire Williams, who has now taken over the running of the team. She desperately wants her father to acknowledge what Ginny meant to him.

As has been well chronicled, the 1970s were lethal years for Formula 1. The cars were flimsy and likened by their own drivers to "death traps." Fatalities were commonplace. Yet Frank seemed to thrive in this atmosphere. Thanks to Ginny, his team stayed in business. Thanks to the engineer Patrick Head, the Williams cars eventually became faster than those of the rivals teams.

Williams himself is a paradoxical character. Ultra-competitive, he seems chauvinistic, self-obsessed and far more interested in the performance of his drivers than in what is happening to his family. The family members, though, are absolutely devoted to him as are most of the drivers and the support staff at the Williams factory. He talks on camera with boyish glee of the lines in Top Gun about "the need for speed." At the same time, he keeps his emotions under wraps. He never gives in to self-pity. He admits he can't even bring himself to read Ginny's book about her life with him.

The fascination of the documentary lies in the way it interweaves the Williams family saga with the story of the Williams Formula 1 team. Matthews casts light on some very unexpected places. Many of the drivers appear on camera, Nigel Mansell, Nelson Piquet and Alan Jones among them. We hear familiar anecdotes about Grand Prix victories, defeats and bust-ups, but this is really a film that is far more about husbands and wives, fathers and daughters, than it is one about men and cars.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments