The happy tedium of simulator games: How developers found magic in the mundane

Whether it’s driving buses or flipping houses, simulators often seem a world apart from the bombast of most video game best-sellers. As 'Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020' lifts the genre to new heights, Louis Chilton looks at one of gaming’s strangest success stories

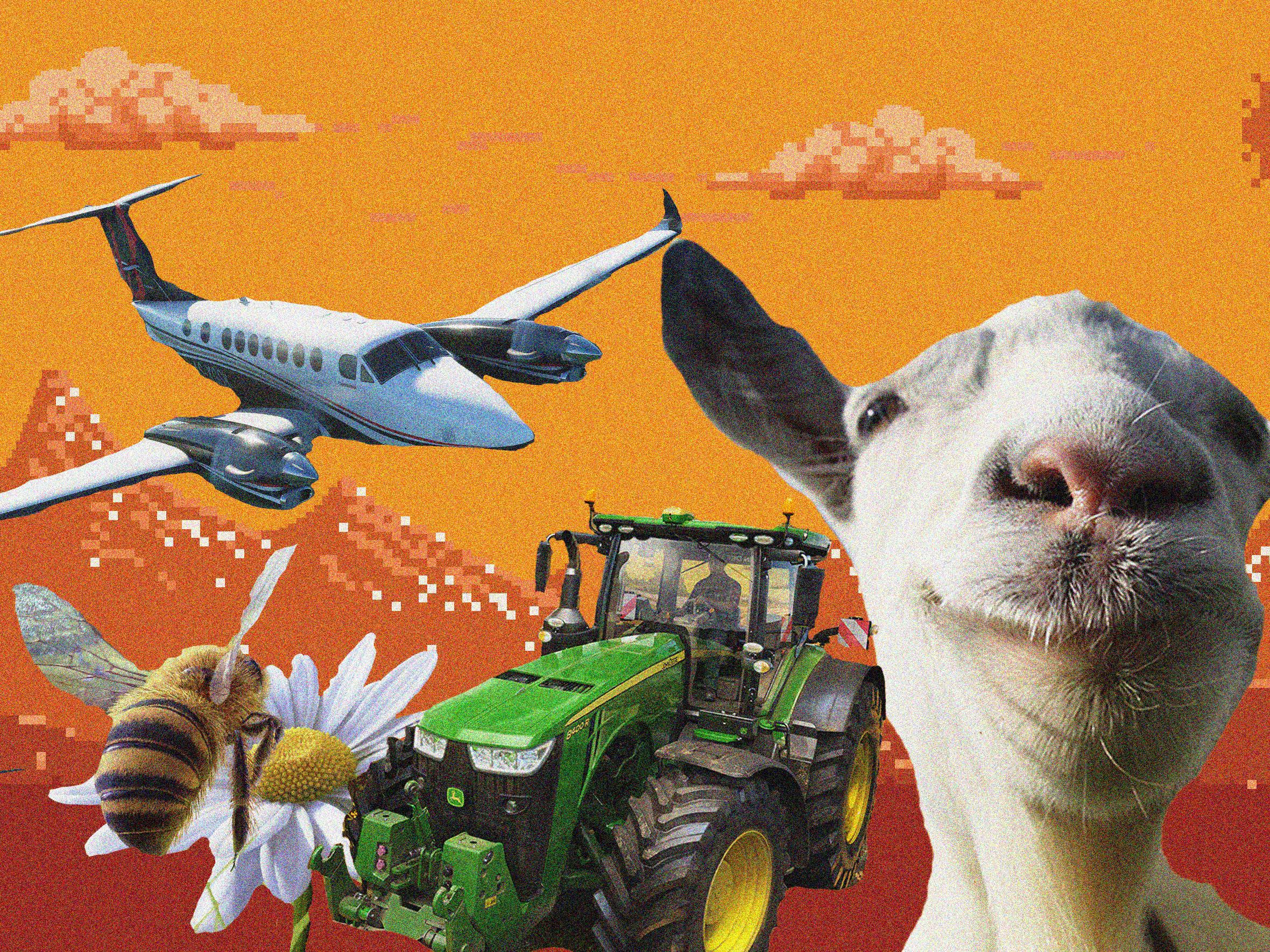

What compels a person to play a game like Goat Simulator? I don’t know, and maybe I don’t want to know. But somebody must have an inkling: the game, a strange, frivolous 2014 romp in which players control a havoc-wreaking goat loosed in the suburbs, has been downloaded millions of times, and became something of a sensation on YouTube and game streaming sites. Goat Simulator is part of a wider genre of simulation games – which includes other bestial fare such as Bee Simulator and Bird Simulator and vehicle simulators like Bus Simulator. There are also all manner of niche others, from PC Building Simulator to House Flipper, wherein the cynically minded player must renovate a virtual house for profit.

What unites these games? Aren’t all games simulators, of sorts? Whether it’s sports simulators (Fifa; Madden), crime simulators (Grand Theft Auto), war simulators (Call of Duty), Jedi simulators (Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order), colonialism simulators (Far Cry) or failure simulators (Dark Souls), the purpose of any video game can usually be boiled down to simulation. When we talk about simulation games as a genre, then, we mean something more exact. The term tends to come with a set of specific requirements: the absence of any real characters or story; the focus on one sort of skill or situation; and, often, a certain deliberate mundanity. Certainly Goat Simulator seems to fit this description, as does Airplane Mode – a yet-to-be-released PC game in which players can experience the thrill of flying… in economy class.

In Airplane Mode, you spend the game kennelled in the first-person viewpoint of a passenger on a commercial jet, able only to stare out the window, gaze at the in-flight entertainment, or eat a realistically unappetising package meal. The only real obstacles you’ll encounter are the shrill wails of an onboard baby, bad wifi, or delays. One presumes such a game is created, marketed and purchased without a shred of sincerity entering the equation at any point. There is humour to be found in humdrum, of course (I once watched a so-called “anti-comedian” perform a perversely dry but nonetheless funny stand-up routine about the minutiae of financial management), and this seemingly counterintuitive approach is a valid USP in an industry built on steroidic action and self-aggrandisement.

Hitting shelves today is an entirely different type of aeroplane-based game, Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020. Placing you in control of an airline pilot, MFS 2020 lets you fly aircrafts over countries and environments rendered with unprecedented detail. The game feels like it’s from another age – graphically leaps and bounds ahead of anything that has come before (it also requires some pretty heavy-duty equipment to play, and the premium deluxe version comes with a sobering price tag of £119.99). It is a vehicle simulator in the purest sense. Outside of official pilot training equipment or the real aeronautical deal, it’s also probably the closest anyone can come to knowing what it is to fly.

Part of the appeal of games like MFS 2020 is the serenity they offer. Flights cannot afford to be hurried and players will spend hours mostly just taking in the incredible views and maintaining a steady hand on the tiller. It’s a far cry from the migrainous action of Call of Duty. This is gaming as psychological decompression: a shift away from the active kineticism of most video games to something more passive. There are similarities with the trend of Slow TV, a surprisingly popular type of Norwegian programming that consists of lengthy, plotless footage of everyday things, such as a seven-hour train journey. A 2015 attempt by the BBC to launch the genre on UK shores (BBC Four Goes Slow) peaked with a two-hour reindeer-led sleigh ride across the Arctic, but Slow TV proved too great of an ask for most British attention spans.

While one of MFS 2020’s key selling points is its breathtaking graphics, other vehicle simulators are less spellbinding – the Euro Truck Simulator franchise, for instance, or Bus Simulator 2018. Nonetheless, these games still sell well – more than 5 million units on Steam, in Euro Truck Simulator 2’s case. It’s not necessarily the detail or artistry of the environments, but the fact that you are given license to simply absorb them, free of rush or distraction. It would be wrong, however, to dismiss all of these games simply as unadorned escapism. Often, there will be some element of strategy involved; in MFS 2020, for instance, the challenge lies in a set of meticulous technical criteria needed to properly pilot the aircraft. In the ever-popular Farming Simulator franchise (the mobile version of which has been downloaded over 90 million times), tranquil, repetitive farming activities are successfully mixed with strategic aspects of agricultural-commercial management.

You might find it strange that games like MFS 2020 are embraced by the very people whose daily lives they aim to simulate. Notes accompanying the game state that the game was designed in correspondence with pilots and aviation experts, with the “community of simmers and aviation” as its target audience. This phenomenon – of people clocking off from their day job, only to load up a virtual facsimile – is by no means exclusive to pilots. I have a friend who’s a mechanic, who admits to playing a couple of different Car Mechanic simulators in his free time. Asked about this lunacy, he provided some fairly simple reasoning. They’re accurate, but mess- and hassle-free, and offer the chance to opt into work he wouldn’t normally get to do. In these games, we are afforded a perfect illustration of the difference between work and labour. The daily unwanted clutter of a profession falls away and the pure work rises to the top, separates like cream from milk.

Lucas Pope subverted the tedium of simulation games with his ingenious 2013 PC game Papers, Please, which placed you in the shoes of an immigration border official. Though the gameplay was purposefully drab and repetitive – assessing paperwork and other immigration documents, refusing passage to any you suspect might not meet standards – it builds to an impactful and devastating political message about cruelty and injustice in immigration bureaucracy. Pope’s previous game, 2012’s The Republia Times, was a similarly slippery endeavour; a game that cast you as the editor of a newspaper in an authoritarian country, tasked with massaging the headlines at the behest of the government. Both games are great examples of the ways in which a politically minded developer can leverage the fundamentals of simulator games into something a little deeper, trickier to define.

Depending on how far you can stretch the definition of a “simulation game”, there are plenty of other games which have pushed creative boundaries. The term “walking simulator” was popularised a few years ago as a derogatory term to refer to story-heavy first-person adventure games (unlike, say, an actual walking simulator such as Bennett Foddy’s QWOP). Though the phrase has since been somewhat reclaimed, “walking simulator” is still used as a cudgel against games even as dense and extravagant as last year’s Death Stranding. In Death Stranding, the simple act of walking – as you deliver packages between two faraway points – turns into its own kind of poetry. Strip away the A-list cast (Norman Reedus; Lea Seadoux; Mads Mikkelson), the auteur director (Hideo Kojima) and the overblown sci-fi storyline, and you’re left with the same core appeal as Bus Simulator or MFS 2020: the sweet, patient pleasure found in a job well done.

Like literature or TV, gaming is a wide and varied world; a game such as Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020 bears no more resemblance to Call of Duty or League of Legends than Game of Thrones does to Mock the Week. While simulator games might seem like simply an updated form of esoteric analogue pastimes like model train-collecting, there’s a reason the industry keeps returning to them. Sometimes we don’t want bombast, we want reality – or maybe just a pleasant almost-reality with the edges sanded off. There’s nothing strange about that.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks