The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

An extract from The Age of Bowie: a glimpse of David Bowie on the brink of stardom

The scrap over a girlfriend that led Bowie to suffer anisocoria, which caused his different coloured eyes, and his first hit single 'Space Oddity'

He takes an interest in girls, and not so much, it seems, boys, although he likes looking at what they wear, and isn’t averse to issuing boasts to friends for the sake of an already developing character he fancies being that he is bisexual. Girls are more his thing though in the real world, and at 14 he and best friend George are eyeing up the same pretty girl, Carol Goldsmith. George gets there first, and arranges to meet her at a local dance hall. Competitive David is not happy when he hears this, and manages to persuade George that she is not interested in him, far prefers David, accepted because she felt sorry for him, and is not going to turn up.

George finds out that she does turn up and waits for him for nearly an hour before giving up. The next day George hears underhand David gloat that he has stolen Carol from George and that she is now his. Furious, wanting to have it out with David who won’t take the bait, confronting his self-serving tactics, a frustrated George abruptly and uncharacteristically punches David hard in the face. His knuckle lands in Davie’s left eye damaging the Iris sphincter muscles. The school is shocked, Owen [Frampton, Bowie's teacher] in particular.

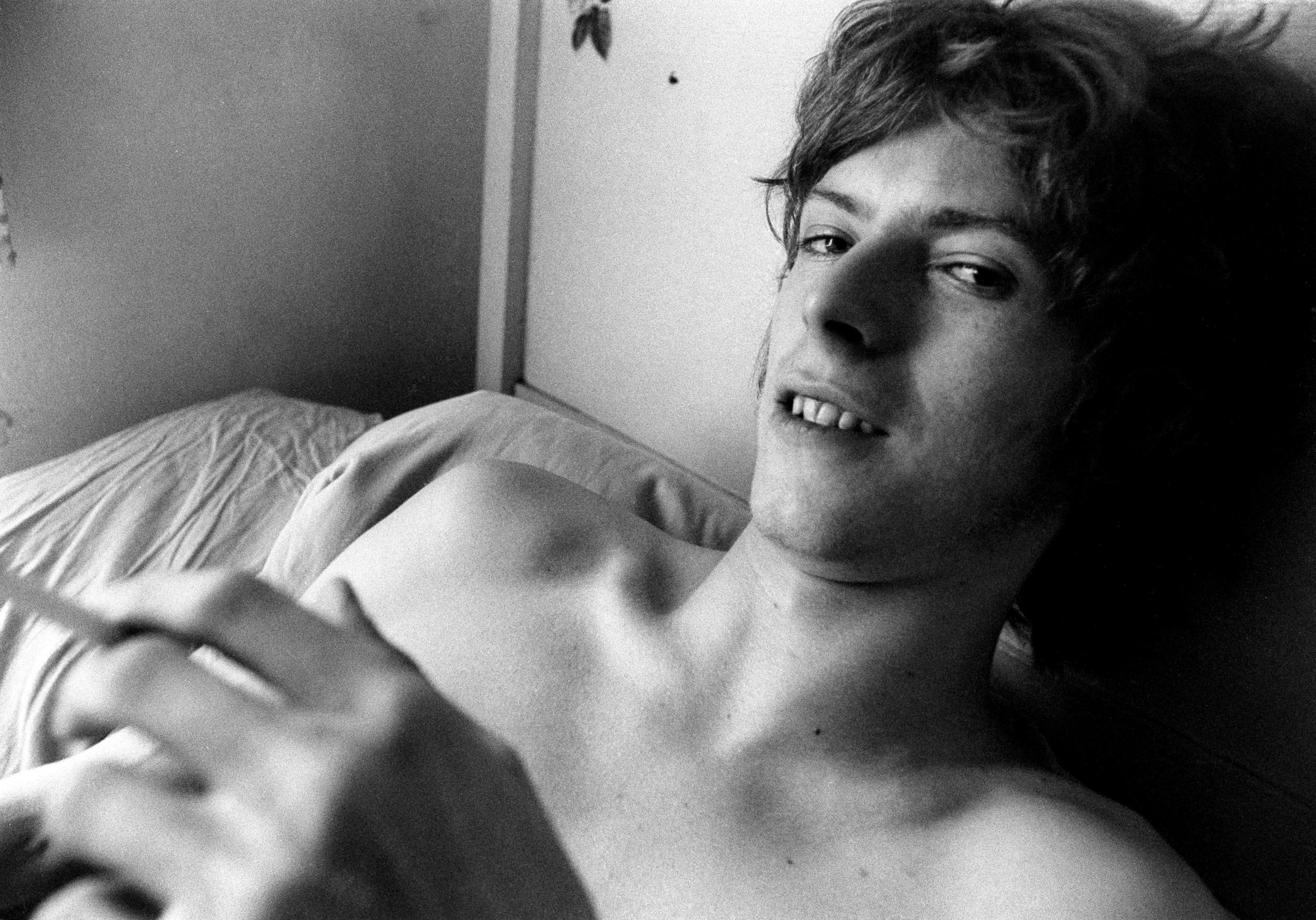

David is rushed to hospital, the eye is saved after weeks of treatment, but the injury leads to anisocoria, a relatively common condition that causes the pupils in each eye to be different sizes. In this case the pupil in David’s left eye would not close after the trauma and a series of operations. In most people who have the condition, it is not as noticeable, just a slight difference in size.

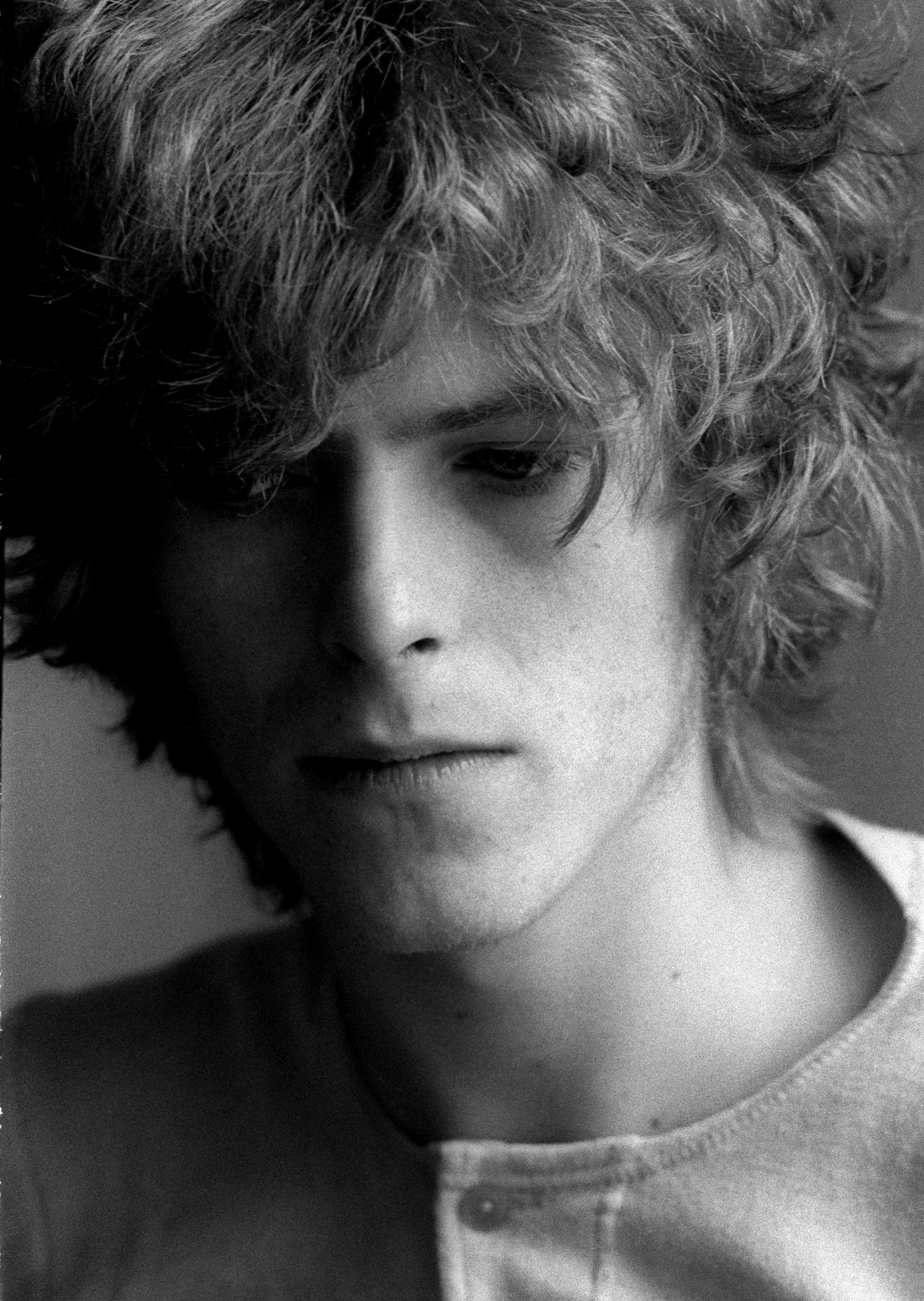

With David Bowie, the difference in size is pronounced, the left eye blotted out by darkness, giving the illusion that one eye is watery blue and the other dove grey, and for the boy who wanted to be different from anyone else, it became an internalised, physical manifestation of his imaginative vagrancy, an ethereal scar, a subtle but categorical distinction, something that set him apart as someone apart whenever he needed to look as though was from somewhere else not of this ruined world.

George was mortified, but over the years David shrugged the incident off, the pair remaining friends, saying that George in fact did him a favour. He would joke that after it happened, he could sing better.

He is officially no longer average. He has a permanent romantic wound that also interferes with his depth perception, giving reality a cubist kick. He can safely feel different and anyone only has to look at him to see the evidence.

It embedded an indelible thread of fugitive originality in his appearance, giving him something he couldn’t have got from anywhere else however hard he foraged. It worked as part of the overall effect when he was dressed up in fully costumed display, playing cold fish, secret agent of change or peripheral being, and it was still there when he was withdrawn, modest and undecorated.

In fact it was almost more eerie when he was more or less off glam/alien duty. Even at his most ordinary-looking there was a tell-tale trace of the bizarre, the seductively off-centre, the unbalanced pupils explicitly the entrance and the exit of his fantastic imagination.

* * * * *

There was nothing left for Davie but to become part of a pop group, get to know what that means, precedents already being set around the country by school friends rapidly learning new chords, acquiring new instruments and techniques and moving on from the very limited almost parodic skiffle. Their groups had names intended to communicate something sharp, modern, stylish, tainted with American-ness, a bit Western outlaw, a bit beat, a bit space-age, very much influenced by Buddy Holly’s backing group and how the Crickets becomes an instant gang brand – there were the Searchers, the Echoes, the Viscounts, the Tornados, the Tremeloes, the Pacemakers, the Animals, there was instant English mischief – Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Tich – and of course the sharp-suited Shadows and the early quick-witted signs of the Beatles, and first hints of a more abstract, poetic style with the Zombies and the Hollies.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

In 1962, Davie Jones joined his first group, the Kon-rads, all 16 and 17, formed by his close school pal George Underwood and Alan Dodds the year before. The name came from a pun on clean-cut singer and actor Jess Conrad, who played a dreamboat pop singer in a play, Rock-A-Bye Barney, and a TV series, The Human Jungle, and is then groomed by television producer and pop impresario Jack Good to actually be one for a couple of pre-Beatle years. Good was inspired by the scandal caused by Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock” to start the first rock-and-roll shows on British television; he thought some of this new energy was perfect for TV. Good’s dynamic new shows had helped launch the first English rock stars Marty Wilde, Billy Fury and Cliff Richard, but Jess made the soft-centred sweet English Elvis Cliff seem like piano-smashing rip-roaring Jerry Lee Lewis. His chart life is all over by 1962, not least because for all his good looks he had next to no voice. An early hint to Davie; get as much voice as you can, even though it might be too much for some.

Davie pestered George for months to let him into the Kon-rads.

George leaves, and he finally becomes the group’s saxophonist and a backing singer after answering an advertisement in a local paper, possibly the only one who did. It was never Davie’s group, and his attempts to jazz things up with distinctive Wild West outfits and sundry gimmicks including a fine kinky quiff, and an early name change for him to Dave Jay, were a little too ambitious for the rest of the group. Davie went for Jay in tribute to the sax-heavy instrumental beat group Peter Jay and the Jaywalkers, never much more than a cult outfit despite being produced by north London Phil Spector, Joe Meek, and supporting the Beatles. They were definitely on Davie’s radar, and an obvious template for Konrad group photos.

A year of solid, low-key semi-pro activity in church, village and school halls performing largely covers of the Shadows, the Beatles, Dave Clarke and Chris Montez and a limited sense of adventure was increasingly frustrating Davie, already hungry to experiment. He was looking to the hipper, more urgent Chicago blues sources that the Yardbirds and Rolling Stones were freely appropriating. The Konrads, finally losing the irritating hyphen, lacked his determination and resourcefulness, and, they were quick to admit, his definite canny charisma – certainly he had more than their main lead singer, and the kind of gifts that made girls pay attention even in the smallest venues. The rest of the group just wanted to play music, have a laugh, get girls, and he was constantly inundating them with ideas, designs, logos, possible musical directions and plenty of new images.

Davie started writing songs with guitarist Neville Wills so they didn’t have to cover songs like Cliff’s ‘The Young Ones’ but they mostly stuck to covering pop hits of the day. Davie would sing Joe Brown and the Bruvvers’ recent hit ‘A Picture of You’ – and a favourite of John Lennon’s at the time, due to some cracking haywire harmonica, American rockabilly singer Bruce Channel’s “Hey! Baby”.

Record labels desperate for new young talent led to an audition at the Decca studios in West Hampstead in north-west London. The local Bromley paper was breathless with anticipation, but Bromley’s pride and joy the Konrads with a lacklustre demo version of their own “I Never Dream” failed to join the Jaywalkers – and the Rolling Stones and Tommy Steele – on Decca Records. But then the Beatles had also failed their audition for Decca at the same studio twenty months before – because guitar groups, according to Decca, were on the way out.

Davie didn’t sing lead, but if he had done maybe the recording wouldn’t have been wiped and we would have got to hear him singing at 16 earnest pop words written by the group’s guitarist, Alan Dodds, about never dreaming he would fall in love with someone whose eyes are, naturally, so blue. On his first ever recording, the first time he’s in the recording studio, where most of the work we think of when we think of David Bowie is done, he’s in the background, and then lost. Soon, by the end of the year, he’s no longer in the Konrads.

* * * * * *

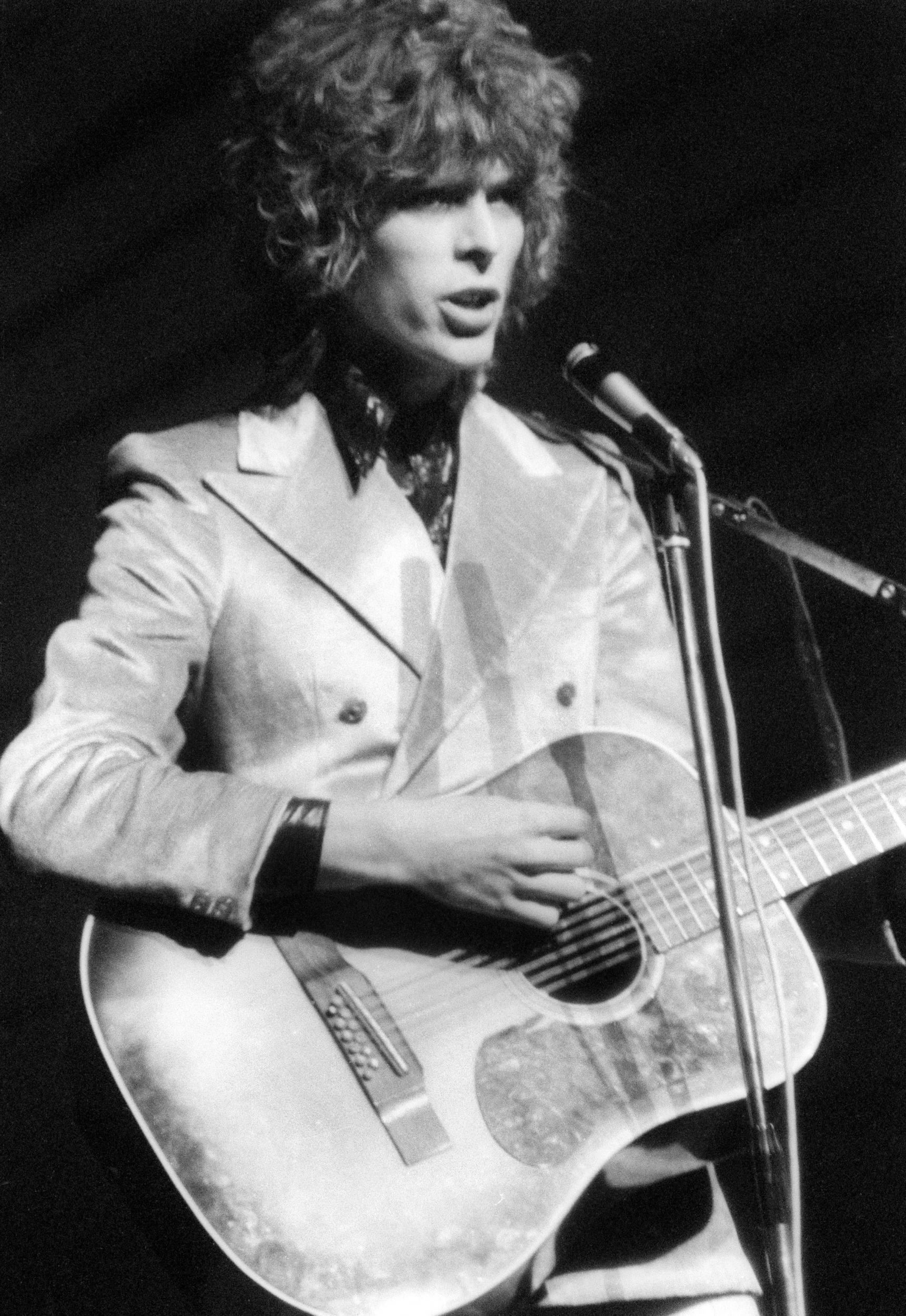

Bowie was still out of phase with where rock was in 1969, not least because he finally had his hit single, which ended up being the novelty hit his new producer Tony Visconti feared it would be when he heard the demo. A close relation to the moony novelty of Zager and Evans than where rock was at the time, it meant Bowie was still apart, still not to be taken seriously.

If you’d bought an album in 1969, you might have chosen one of the greatest of all time – Captain Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica – or Nick Drake’s Five Leaves Left, the Velvet Underground’s third, Iggy and the Stooges’ The Stooges, King Crimson’s In the Court of the Crimson King. Or you’d have got something iconic by the Beatles (Abbey Road), the Who (Tommy), the Rolling Stones (Let It Bleed), Led Zep (II), Scott Walker (Scott 4), Sonny Sharrock (Black Woman), Johnny Cash (At San Quentin), MC5 (Kick Out the Jams), Crosby, Stills & Nash (Crosby, Stills & Nash), or Frank Zappa (Hot Rats). The Band and Neil Young were debuting, Dusty was in Memphis and Joni Mitchell was in the Clouds. The best you could say was that in a year of singles like ‘Proud Mary’ by Creedence Clearwater Revival, ‘Honky Tonk Women’ by the Rolling Stones, “I Want You Back” by the Jackson 5, “I Wanna Be Your Dog” by the Stooges, “The Ballad of John and Yoko” by the Beatles, “Space Oddity” was not that far off the very best. Bowie was sneaking closer to the centre, even if that was only much clearer later, not at the time.

As soon as his first hit single started to drop from the charts, Bowie tumbled with it, falling back to earth. He wasn’t destined to be remembered because of “Space Oddity”, not at the time. For a while it seemed as though it would become his own tin can that he was sealed inside, drifting off into ultimate obscurity, never able to contact planet earth again in the same way.

It was given the Ivor Novello Record of the Year award along with Peter Sarstedt’s “Where Do You Go To (My Lovely)?”, another one of a kind song using a beguiling, aching folk- based ballad to smuggle an existential map of the mind into the hit parade. For a few months, but those few months felt like an eternity, Bowie seemed as though he would drift away like Sarstedt into an endless 1960s, repeating his one hit over and over again whatever else he tried as it and he became tragically retro-futurist. Forced in the first place to exist out of synch in the wrong time and space, he would be stuck there forever, perpetually a few seconds from a death he has come to accept but never quite floats into.

“Space Oddity” was just another character he played for a while. Because it wasn’t all he was, eventually he would escape its pull. He was ready to take on more characters, and now he’s been into space, transmitting the collapsing, ultimate adventurer’s mind of Major Tom, everything he did next would have that aura of the space explorer. He disappeared around the other side of the moon for a while into the darkness, but he would soon reappear, returning to a changed world, heading for a hero’s reception.

This is an extract from The Age of Bowie, by Paul Morley, published by Simon & Schuster, £16 from https://www.waterstones.com/book/the-age-of-bowie/paul-morley/9781471148088

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks