American dreams: Bruce Springsteen's glory days are back, thanks to his songs with a political conscience

When Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band headline Glastonbury tomorrow, most fans will doubtless get the barnstorming rock'n'roll show they made their name with more than 30 years ago. But Springsteen's weighty place in critics' hearts has to do with a more desolate strand in his work, a faded Americana adapted from the Depression laments of protest singer Woody Guthrie and John Steinbeck. This led to his very best songs. But forced worthiness rewarded by unquestioning critical reverence has been the other result of Bruce's double-life as dustbowl troubadour.

Springsteen's ex-rock critic manager Jon Landau is credited with educating him away from the escapist street-romance of his 1975 breakthrough Born to Run. It was Landau who handed him a Woody Guthrie biography, and guided him towards Robert Frank's 1950s photos of lonely roadside Americans and John Ford's film The Grapes of Wrath.

The idea that Springsteen was manipulated into acting out his mentor's literary fantasies is tempting, but the initial results can't be faulted. Darkness on the Edge of Town (1978), The River (1980) and Nebraska (1982) are his work's core. The previously apolitical singer wrote Nebraska under Guthrie's influence, as a stark tour of the small-town America he grew up in, laid waste by Reaganomics. The River's title song remains his best. Its young married couple in a closing factory town have no future in a way more crushingly solid than punk's teenage mantra. "Is a dream a lie if it don't come true/ Or is it something worse..." the man wonders, of an American Dream he has been forced awake from. It was a heartbreaking political song because it barely looked up from personal concerns; as good as Guthrie, but Springsteen's own.

When Born in the USA repackaged all this for the mainstream, Reagan half-heard its title track's raging Vietnam vet, and allied his 1984 re-election campaign with its "message of hope." Springsteen bitterly suggested Reagan's favourite song by him probably wasn't on Nebraska.

His true bid to be a new Guthrie came a decade later, and allowed no such confusion. He'd sacked the E Street Band, bought a Hollywood mansion, and found himself facing, as he wrote in "Better Days", "a sad funny ending/ to find yourself pretending/ a rich man in a poor man's shirt." The Ghost of Tom Joad (1995) was his response; an acoustic album about the plight of migrant workers in America's south-west. Springsteen clearly felt the subject was so grave he mustn't sully it with tunes, making reading the lyrics more satisfying than listening. Fans dubbed the resulting shows the "Shut the Fuck Up Tour", the Boss's regular advice to anyone who talked over his agitprop dispatches. Mainstream compromises were sent packing (once he had reaped their rewards).

But artistically, Springsteen was fooling himself. The templates for his reinvention as a "serious" writer were from a tradition he couldn't even remember. Naming The Ghost of Tom Joad after The Grapes of Wrath's Depression martyr, and the replacement of his usual obsession with cars by railroad tracks in Nebraska and Joad tell you how distanced and imaginary this antique Americana was to him. His sense of mission was framed by old records and films. His real background was Jersey, his home Hollywood. The wider, modern world of Mexican migrants came from reading the papers. LA Times reporter Mark Arax told Bruce biographer Christopher Sandford of giving the singer "cheat notes" on the subject. "Bruce's own heroes would probably have gone... and seen for themselves," he said. The whole affair seemed about an adrift Springsteen reconnecting with himself, as much as helping his country.

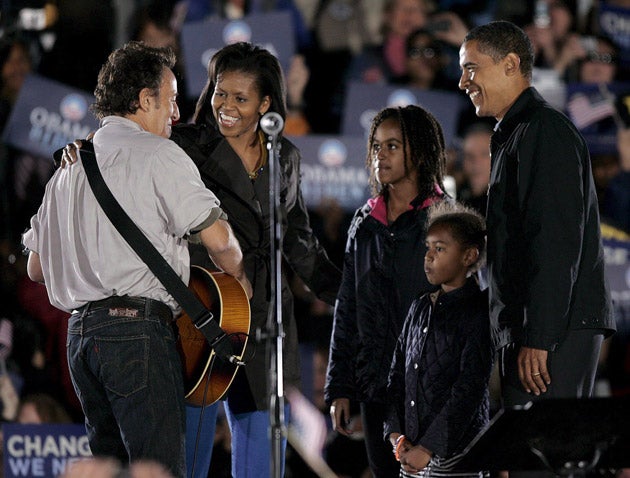

Even when he reformed the E Street Band, the resulting albums were now political broadsides. The Rising (2002) set out to heal 9/11's wounds; Magic (2007) attacked Bush's re-election and the Iraq War with some of the old swagger. Even this year's goofy pop release Working on a Dream was reverently received as Bruce's latest tablet on the state of the union. The personal void looming out of The River, given mythic shape but felt in its writer's heart, was what was missing in such windy Responsible Rock.

But in between these over-praised works, a tribute to Guthrie's near-contemporary Pete Seeger showed Springsteen earning his troubadour heart. We Shall Overcome: the Seeger Sessions was a jug band riot you could dance to, unlike po-faced Joad. "How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live" had new verses scrawled in fury by Springsteen at Bush's post-Katrina neglect of New Orleans. Watching tour footage of his lips curling in concentrated disgust as he sings it, you know that however contrived his journey to that spot, he is finally standing in Guthrie's shoes.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks