‘It costs a lot of money to look this cheap’: How your favourite pop stars’ costumes are made

The world’s biggest music stars have long relied on stylists to craft their iconic images. Behind every unforgettable look is someone working overtime – stitching, styling and sometimes spraying vodka – to make sure the show goes on, discovers Michael Hann

It is a Thursday night in July 1972, and a one-hit wonder from a few years earlier has been given another shot at Top of the Pops. The camera slowly pans back to reveal the singer, who wears what appears to be Joseph’s Technicolor Dreamcoat transformed into a jumpsuit, his hair a bright orange coxcomb. His guitarist looks, literally, like Adonis: he is gold from head to toe, hair and clothes and instrument.

Across the course of three and a half minutes, David Bowie changed the course of his life. And it wasn’t just because “Starman” was a great song; it was because every single person who saw that performance remembered what it looked like. That’s how Bowie, draping his arm round his guitarist Mick Ronson, the two of them looking like joyfully dissolute elves, communicated to a million kids that they, too, could be something else.

Which is why what a musician wears matters, and why most successful ones have stylists and designers on call. For many artists, it’s just a question of stage clothes, with the occasional outfit for awards and parties. The lucky few (usually men, but also Chrissie Hynde and Joan Jett) can get away with a leather jacket and jeans for all occasions. But for some stylists, keeping a star glittering is a full-time job.

Steve Summers has been Dolly Parton’s creative director since 2006 (on appointing him, Parton sent him straight to the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York to get up to speed), and has styled her for over 30 years. He is responsible for how she looks at every public appearance, and for liaising with her brand partners to ensure everyone gets the Dolly they deserve.

There are certain rules he observes, he says. “Number one, it’s going to be form-fitting, no matter what. She has a beautiful, beautiful form, and so it is going to showcase her body. It is going to be interesting and intricate, and that doesn’t necessarily mean busy. It just means you’re going to notice details. It’s going to match her personality – she exudes energy, and I try to make the garment match the humans.”

Any particular favourite colours or fabrics? “She’s like a butterfly: there is no colour that doesn’t work. She has preferences: if she’s on stage, she loves to wear white. If she wants to be vibrant, she wears bright yellow, or pink, or peach. If she’s trying to be dramatic, it’s blacks or greys.”

It was Parton herself who told critics, “It costs a lot of money to look this cheap.” And, as Summers says, “she will be the first to tell you that is no joke. It costs a tremendous amount of money – but I don’t think the average person does 300 events a year.”

So that’s 300 outfits he has to give Parton each year. “I would guess 100 of those are made, and 200 are bought. There’s something in production all the time. It’s not uncommon for her to have 10 changes in a day, but those things are usually very specific for a specific vendor partner, and you’re trying to make sure the branding is in line.”

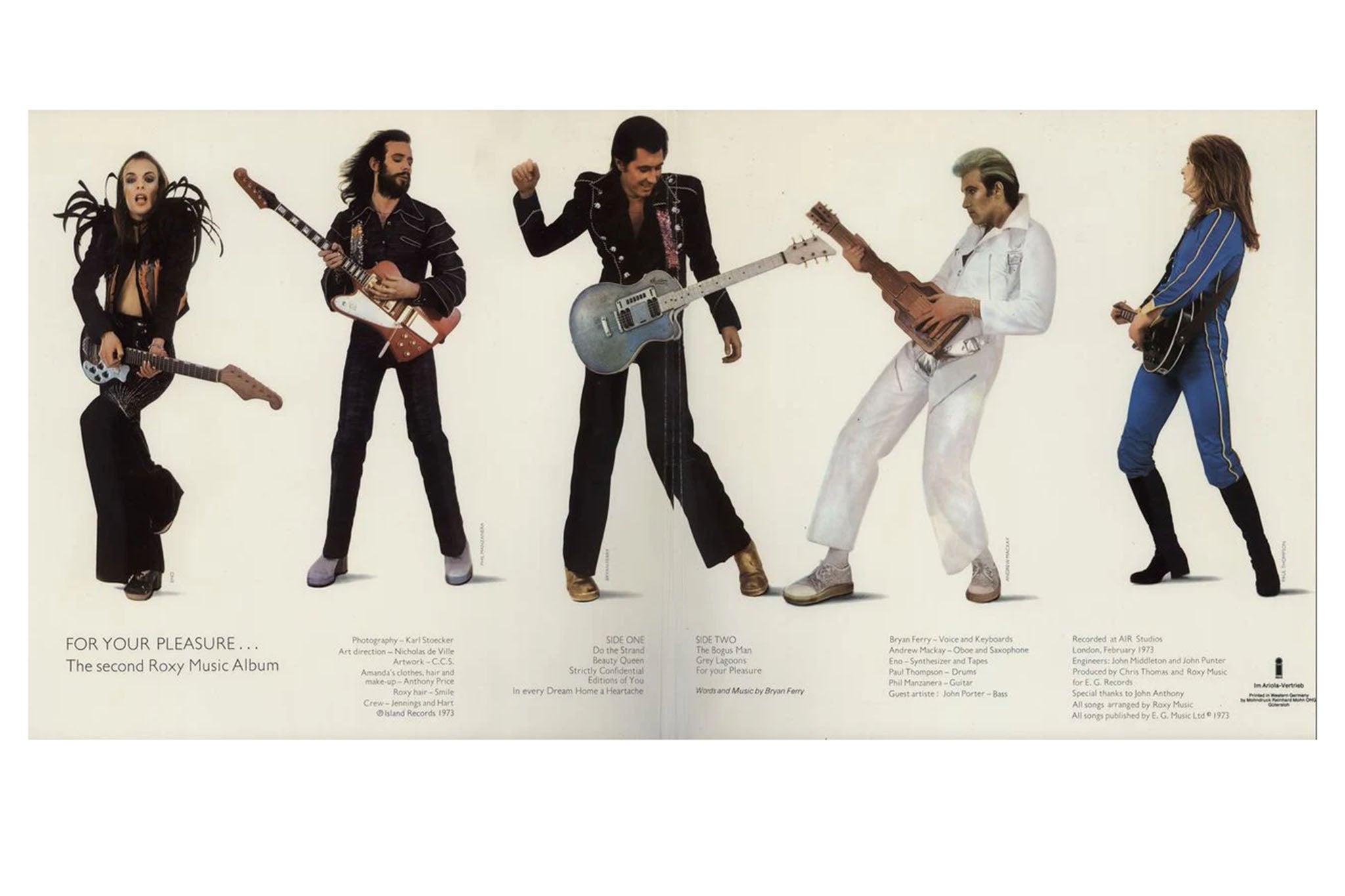

One of the first designers to see his clients as a brand – and certainly one of the first to effect such a dramatic transformation in them – was Antony Price, who began working with Roxy Music in 1972, when he was 26. He worked on all their album covers (he dressed the models on those hyper-glamorous early albums) and styled the band. More than that, over the course of the 1970s, he was the enabler in frontman Bryan Ferry’s transformation from northeastern grammar school boy to country squire.

It all began by accident. He had dressed model Amanda Lear for the cover of the second Roxy album, For Your Pleasure, and turned up to the shoot with bagfuls of the menswear he made in his day job with the fashion house Stirling Cooper. “We stuck the clothes on them,” Price says, “and they’re all howling with laughter because it was totally ridiculous.” Those were the space-age outfits that appeared on the gatefold of the album – though the rest of the shoot, almost unimaginably, featured them dressed as they had turned up, “how most boys from the sticks looked in 1972 – washed-out denim flares with long divorcee hair. I was into something else completely: at the beginning of the Seventies, I was starting to do the Eighties.”

Once that image was unveiled, Roxy couldn’t turn back. “From that moment on, the audience at the first gigs expected them to look like that.”

Price, a man with a refreshing lack of modesty – and much to be immodest about – sees himself not just as a pioneer of musicians as brands, but of the entire move away from print media gatekeeping culture, to it becoming a mass-communication phenomenon. Not quite by inventing social media, but not far short.

“I foresaw the importance of TV,” he says. “In those days, Top of the Pops was important, but the big magazines had been able to decide what the public were going to like. They took the photographs, and they picked and chose. Well, I knew damn well what the film camera was going to do.” So Roxy’s first Top of the Pops appearance – performing “Virginia Plain” on 24 August 1972 – wasn’t just promoting a song, but beaming an alien presence into the nation’s living rooms. “So this was going straight to the public, and that’s what happens now, of course.”

Of course, it helped that “Virginia Plain” was a brilliant song, but it was one of the defining TOTP debuts: there was Ferry – Elvis with a mullet and eyeshadow, in glittering black – behind an organ. On the other side of the stage was Brian Eno, swaddled in faux fur, the four between them in primary colours but for drummer Paul Thompson in an off-the-shoulder leopardskin print number.

Roxy was always a sideline for Price, alongside his couture career, but he treated each album campaign like the annual fashion shows, with a new look and concept for each record cover and tour, overseeing each new Ferry look (Airline pilot! Military officer!). In truth, Price says, Ferry had already reached his ultimate aspiration when Price dressed him for the cover of the 1974 solo album Another Time, Another Place, in white dinner jacket and black tie. “He always wanted to be an established, Sunday Times-acceptable, country…” Squire? “Thank you. I wasn’t going to say it. That’s what he wants to be. But you have to remember, those people don’t buy clothes. They inherit everything.”

Somewhere, a couple of hundred miles northwest of Stockholm, is a warehouse containing costumes and props from Robyn’s videos and tours. “Probably all the glue has gone by now,” says Ellinor Eklund, laughing. “But we’ve joked about that becoming a museum of costumes for her.”

Eklund worked with Robyn towards the end of the Noughties, beginning with 2007’s “Konichiwa Bitches” video. She came on board as a set designer, had to design the outside costumes for the clip, and evolved into being a designer for the star, who at that time was asserting her independence and starting her career afresh.

Making a piece for a video shoot is very different from one for a tour: it only has to last a couple of days, rather than a couple of hundred. And it has to work from every angle. In some ways, Eklund agrees, it’s more like making a site-specific piece of art than a costume. On the “Konichiwa Bitches” video, she says, “The costumes were impossible to dance in – she had to adjust to the costumes, and she couldn’t have cooperated with a choreographer. When you are making a costume just for a video, it can be uncomfortable and hard to wear – it’s amazing, really, for a star to let go and accept what they’re going to wear for that day’s shoot.”

Both Eklund and Summers stress how important it is to be trusted by the artist: a stylist making a terrible decision has the ability to make any previously cool singer look deeply stupid. And there are some circumstances where you can plan all you want, but still have to hope for the best. Such as when Dolly Parton played Glastonbury.

“It was very muddy,” Summers remembers. “But it did not rain on her. God and her apparently have a deal. But we had taken precautions.” Precautions didn’t mean a spare pair of jeans; it meant a fully loaded trailer with choices of outfits for every scenario, weather-wise or social. “There’s multiple pairs of shoes. There’s multiple pairs of earrings and rings and necklaces, etcetera. There’s multiples of everything, because you never know when something's going to happen. You could pop a zipper, buttons could break. Stones could fall off a dress, it could get ripped. You could step on something. Wrong things happen all the time, but because of the fact that she is a pro, she has taught me to make sure that I’m prepared for those things. So either I have a sewing kit or I have an extra outfit, or I have two pairs of shoes, or I have five pairs of earrings. Whatever it is, I’m prepared, because she’s taught me it.”

Sometimes, though, artists are not the greatest repository of wisdom about their dressing choices. Tod Junker has been designing costumes, largely for metal bands, since moving to LA at the turn of the century: you want a horned helmet and a leather coat weighing 18lb to wear on stage – as Shagrath of Dimmu Borgir did – then Junker is your man.

The roots of Junker’s career lie in being a kid watching Star Wars. “I was fascinated, because everything was dirty.” He saw a film costume designer interviewed on TV and was astonished by the tricks of the trade – even things as simple as sandpapering leather to scuff it. He started working with leather, and – as a rocker himself – found rock clients coming to visit: his first job was a pair of leather trousers, for Lenny Kravitz. From metal, his look spread more widely – both Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera wore Junker’s designs during their leather phases.

One thing about leather, he says, is that it doesn’t fall apart. It lasts forever, so it’s ideal stagewear, in some respects. Not so much in others. “The worst thing that’s going to happen to leather is that it will get crusty, because of all the sweat.” And when you have clients whose attitude to personal hygiene is uncommitted, the results can be horrible. “The first time I worked with Vince Neil [of Mötley Crüe], he sent a pair of jeans from the road so I could take a measurement. Vince doesn’t wash anything. It stunk up the whole apartment for a week. It was nasty. But the trick is you flip everything inside out and spray it with vodka and water. It’s not like they’re getting put through a washing machine every night, and it helps them last longer.”

Next time you’re at a big stadium show, and see the star go off four times in a show for a new look, spare a thought for the poor so-and-so who won’t even get a mention from the stage, but without whom there would have been no costumes to change into. Without their look, you wouldn’t be hearing the music.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks