Murder fantasies, fights, pranks and obsessive fans: The story of Eminem’s Marshall Mathers LP

The success of The Slim Shady LP made Eminem conservative America’s worst nightmare, but he was about to prove ‘If anything I got worse’, serving up an album of vicious attacks on everything that moved. Mark Beaumont revisits a musical phenomenon

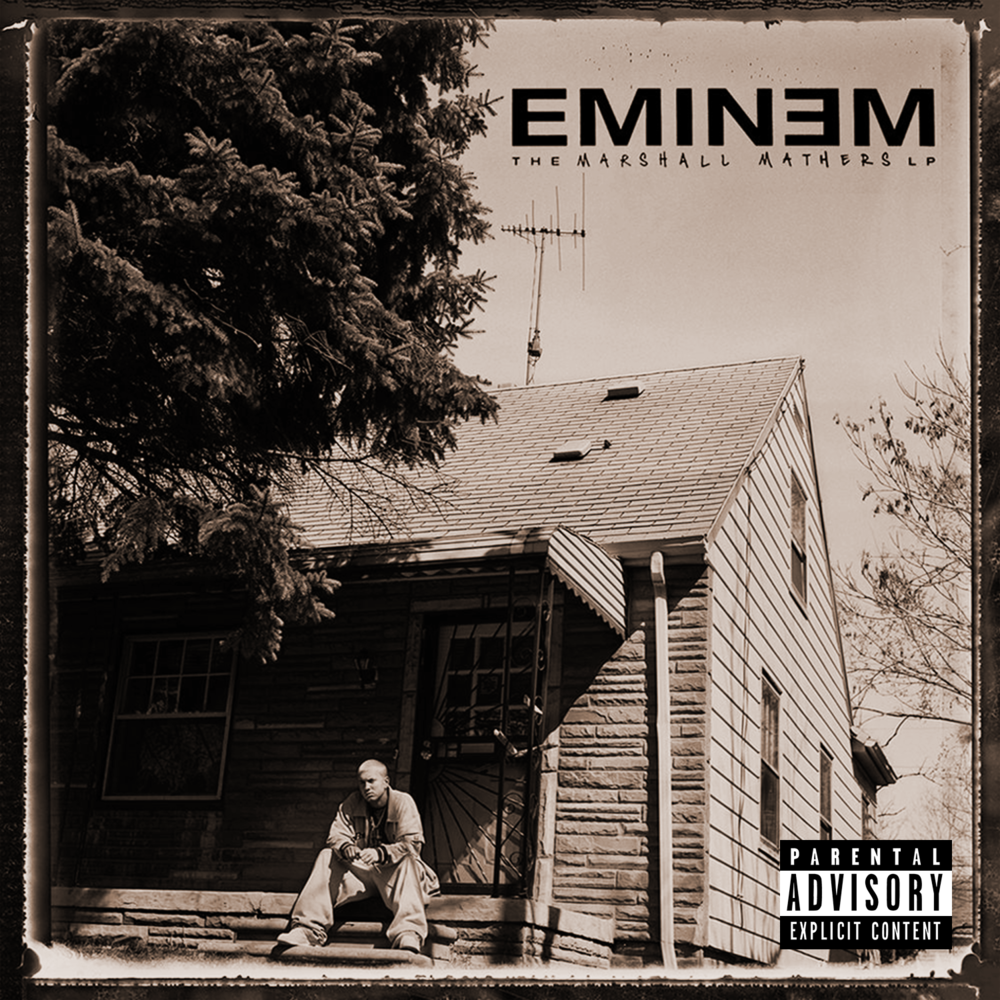

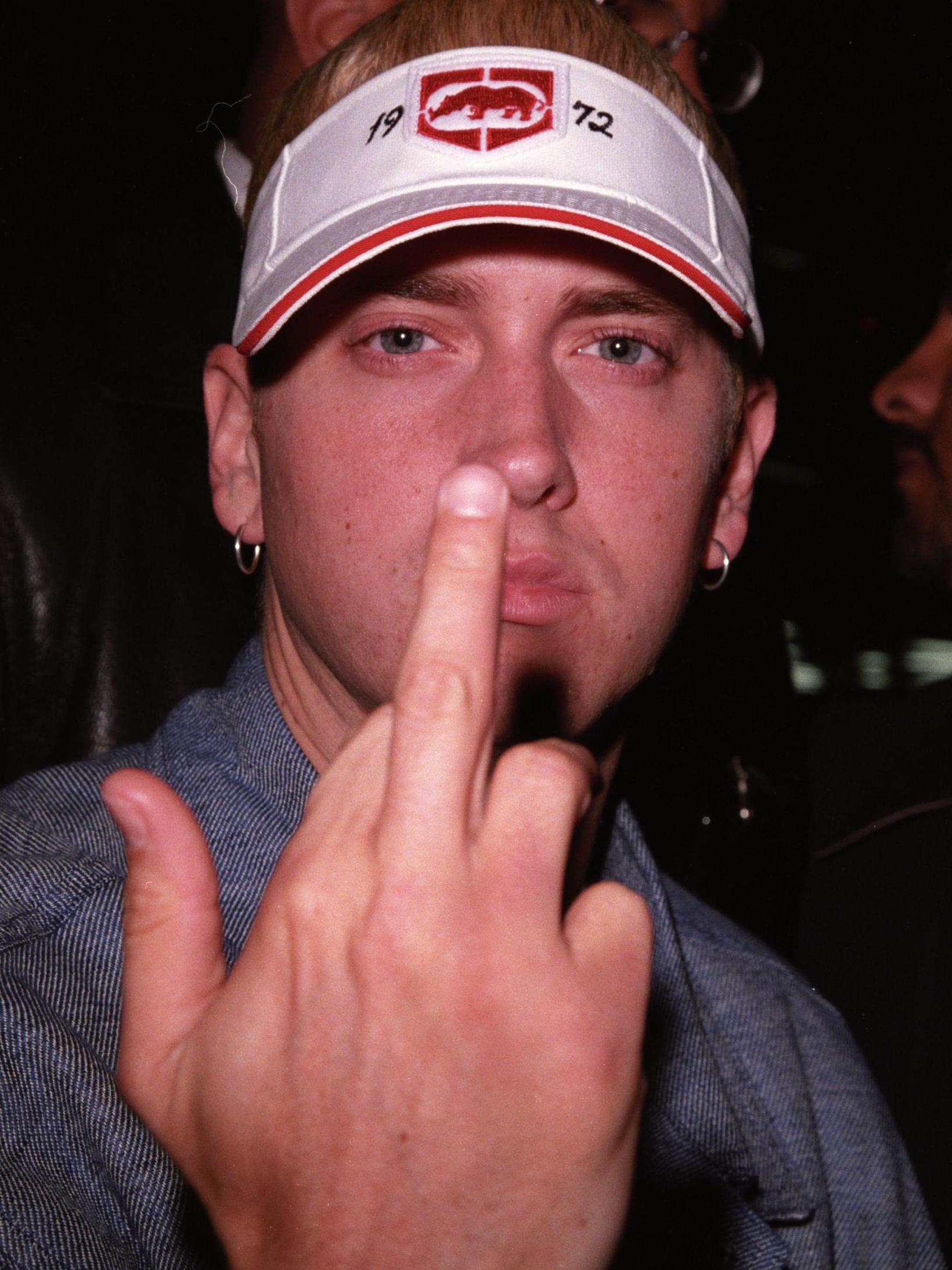

There’s a million of us just like me,” rapped 2000’s public enemy number one as he led an army of clones in white T-shirts and peroxide crew cuts through the streets of New York and into Radio City Music Hall, there to hijack the 2000 VMA Awards. It was conservative America’s worst nightmare, an invasion of trailer trash psychopaths come to stamp all moral values beneath their box-fresh sneakers and convert the nation’s impressionable youth to their war against decency. And they were there to unleash their psychological neuroweapon on the world: The Marshall Mathers LP.

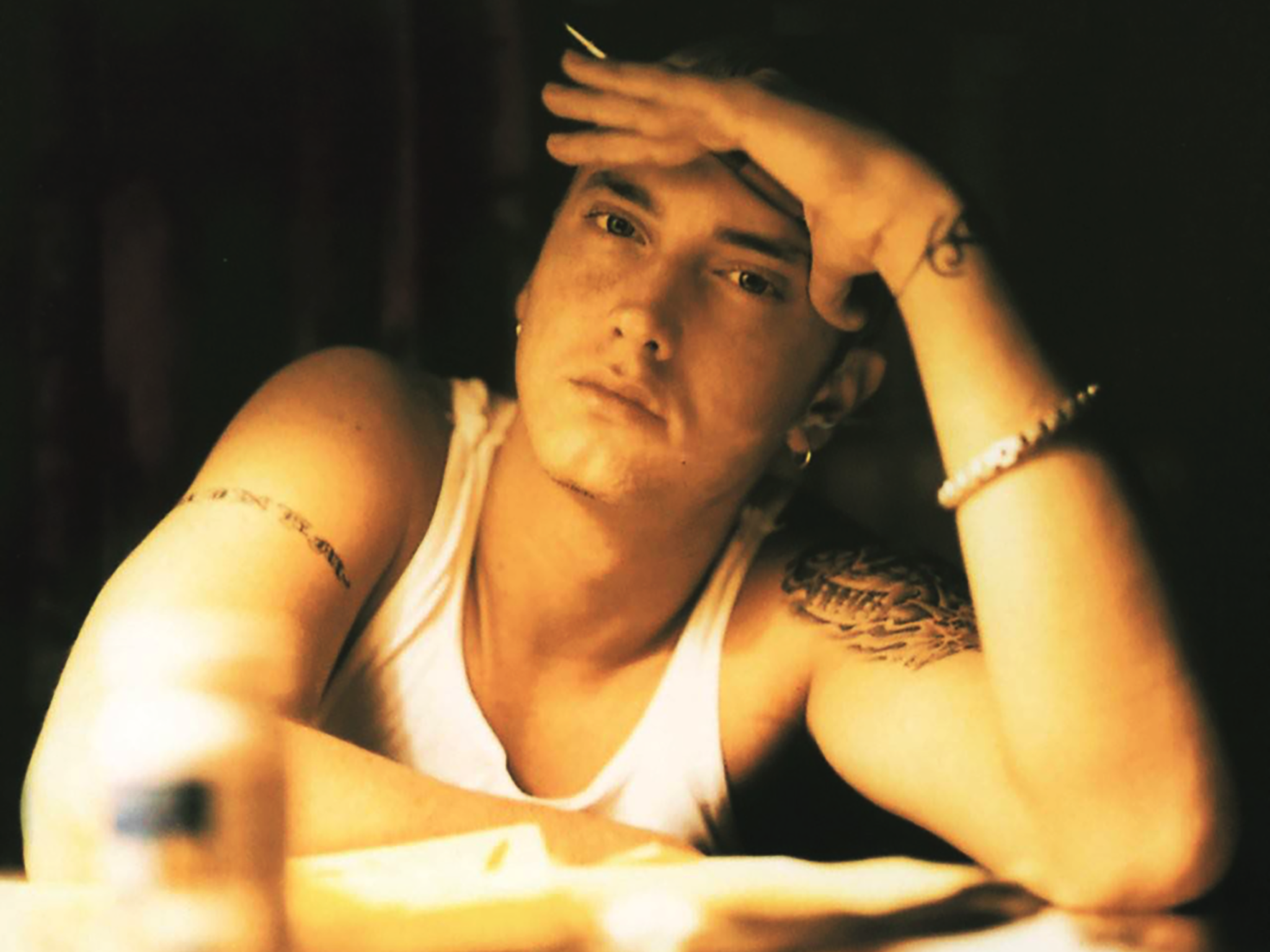

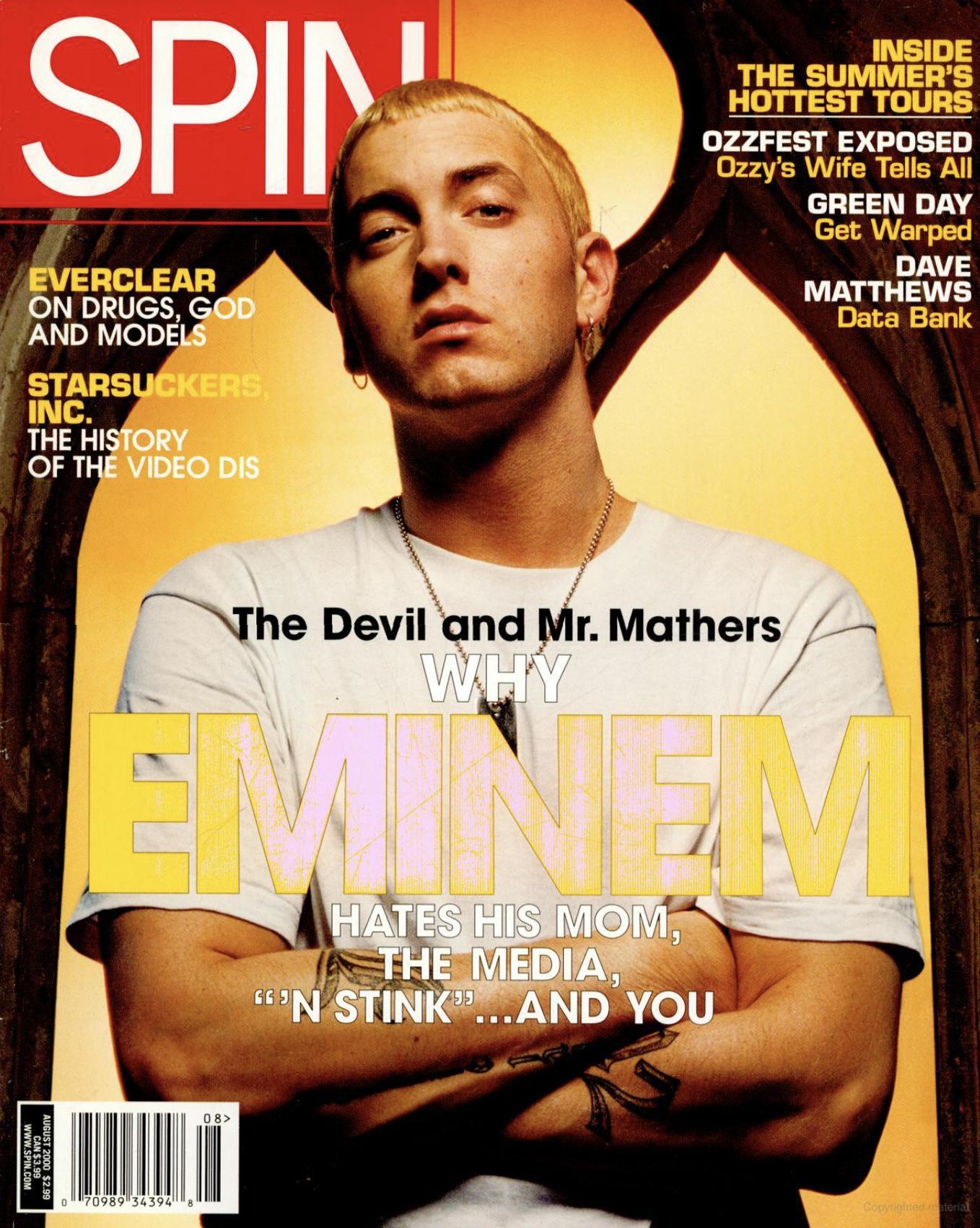

When Eminem’s 1999 major label debut album The Slim Shady LP hit No 2 in the Billboard chart and sold 4 million copies, it sent shockwaves not only through the hip-hop community – here, after all, was a mouthy, blue-eyed white kid capitalising on black culture with a cartoonish horror-movie exaggeration of gangsta rap – but across America. Pinning his profile onto the evidence board, it looked pretty damning. Under the alias of his split-personality alter ego Slim Shady, he’d made on-record confessions of murder, rape, DUI and at least one deeply libellous statement about Christina Aguilera. But the part that wasn’t Slim Shady had his own problems. Background: broken-home Michigan malcontent; absent dad, argumentative mom; history of drug, alcohol and solvent abuse; troubled marriage; and lawsuits against him from members of his own family. Self-proclaimed character traits: homophobia; misogyny; violent anger issues; psychopathic and sociopathic tendencies; revenge fantasies; and chronic victim mentality. This sneering little punk was undoubtedly a menace to society.

From Billboard magazine editorials to tabloid exposés on his troubled relationships with long-term girlfriend Kim Scott and mother Debbie Mathers, Marshall Mathers III was demonised, but not demoralised. This denizen of Detroit’s 8 Mile trailer parks-turned overnight hip-hop supervillain vowed that the first album he would make with the world’s eyes on him would double down on the controversy, confrontation, violence and shock tactics. It would state his case as modern America’s haunted mirror, reflecting the immorality of the Bill Clinton/Monica Lewinsky affair and the brutality of the Columbine High School Massacre, but as free of responsibility as any extreme fiction or sadistic satire. It would purposefully rile the musical mainstream and its most high-profile pop puppets, as well as anyone taking Slim Shady and his murderous outbursts seriously. By letting his sharp, serrated rhymes fly with unflinching honesty, he would prove himself a worthy pretender to the hip-hop throne by making The Marshall Mathers LP – a 20 million-selling phenomenon released 20 years ago today – a malevolent masterpiece, defiantly designed to trigger his critics.

“If you think I’m an asshole, then I’m gonna show you an asshole,” he told Spin of a record that would see him criticised in the US Senate and almost banned from Canada for hate crimes, but also become one of the fastest-selling acts in the world. “If you call me a misogynist, I’m a misogynist. If you say I hate gay people, then I hate gay people ... People started calling me shit, so I just became whatever they said I was.”

“I felt like Marshall was part of this wave with Quentin Tarantino, Pulp Fiction and Reservoir Dogs,” says Mike Elizondo, who played keyboards and guitars on the album. “This next level of art with incredible graphic imagery that Marshall had the ability to paint. Love it or hate it he was obviously very skilled at the stories he was telling.”

Even before Slim Shady began terrorising America in earnest on The Slim Shady LP, Eminem was already making its follow-up more extreme. With Slim Shady, Mathers had channelled the pent-up anger and frustrations of the years spent raising his daughter Hailie in his mother’s trailer on a minimum-wage dishwasher’s salary into an amalgam of radio-friendly bubblegum rap hooks and lyrics about self-mutilation, drugs, suicide, date rape and murder on tracks such as “My Name Is” and “Guilty Conscience”. On “’97 Bonnie & Clyde”, he’d also dramatised a car journey with Hailie to dispose of Kim’s body in a lake; perhaps unsurprisingly, the couple split before the album was even released. So, between recording The Slim Shady LP and unleashing it on the world, a trip to the cinema late in 1998 inspired the freshly single Mathers to write Kim a love song.

“I didn’t want to make a corny love song,” he explained in his 2000 book Angry Blonde. “It had to be some bugged-out shit… I don’t remember what movie it was, but I do remember feeling the frustration of us breaking up and having a daughter all in the mix. I really wanted to pour my heart out, but yet I wanted to scream.”

Returning to the studio, he set about writing a prequel to “’97 Bonnie & Clyde” called simply “Kim”. Recorded in one take with Eminem playing both himself and his victim, this “love song” rewound the story to detail her murder in graphic and chilling verses delivered almost entirely in deranged screams and sobs, ending in a psychopathic cry of “Bleed, bitch, bleed!” that seemed to emanate straight from the jaws of hell.

“The mood I wanted to capture was that of an argument that me and her would have,” he wrote. “You never would’ve thought but I played it for her once we started talking. I asked her to tell me what she thought of it. I remember my dumb-ass saying, ‘I know this is a f***ed-up song, but it shows how much I care about you. To even think about you this much. To even put you in a song like this.’”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

“Kim” would be deemed too extreme to make it onto the “clean” edition of The Marshall Mathers LP, but it certainly set the tone. And over the coming year his success, notoriety and wild-child attitude would provide Eminem with plenty more frustrations to air. As his fame exploded he tried to keep himself grounded and avoid paparazzi attention by staying in Detroit, but soon found himself fielding visits from strangers and money-moths at his sprawling new home on Hayes Street – “everybody wants to come around like I owe ’em something”, he’d rap.

When not in residence, he partied heavily, drinking and fighting to the degree that he’d need a bodyguard to protect him from himself. “I was always f***ed up. Life was like a big party for me. It was the first year that I blew up and I did a lot of celebrating,” he wrote, and later elaborated in his 2008 autobiography, The Way I Am. “When I was drinking, I could be in a good mood – just loving everybody and feeling like everything was great – then somebody would say the wrong shit to me, and before you knew it, there was nothing my bodyguards could do to stop me from ... punching, spitting or kicking a few times before they could get to me.”

Such hedonism would fuel “Drug Ballad”, an open love letter to alcohol, ecstasy, solvents and prescription meds; his addictions would culminate around 2004 in a habit of 60 Valium and 30 Vicodin painkillers a day. But it was “Marshall Mathers”, probably the most personally revealing of the tracks on its parent album, that would lay bare many of the issues hounding Eminem in the year following Slim Shady’s first chart killing spree.

Here, he devoted half a verse to an eye-wateringly homophobic attack on clown-faced horrorcore duo Insane Clown Posse (ICP) in reference to his first major beef. A disagreement over Mathers printing flyers suggesting ICP might make a guest appearance at the launch party for his early Slim Shady EP had escalated until ICP fled a Detroit club with Eminem and his crew paintballing their car. He also targeted Britney Spears, Backstreet Boys, NSYNC and New Kids on the Block (“suck a lot of dick/ Boy/girl groups make me sick”), exposing his discomfort with the mainstream company he found himself keeping.

“Ultimately he wanted to be taken seriously as a rapper,” says Elizondo, “and with that popularity, he wanted to make sure he differentiated himself from the mainstream. Some of those lyrics where he’s poking fun at other celebrities and artists of that era were a strategic way to make sure he didn’t see himself in that same crew.”

Of all of the revelations in “Marshall Mathers”, though, the family stuff clearly cut deepest. As a teenager, Mathers had written several letters to his absent father all of which had been returned unopened. So when his half-siblings from his father’s family in LA reached out to him in the wake of his success, he was particularly scathing about it in rhyme. “All of a sudden I got 90-some cousins,” he spat, “a half-brother and sister who never seen me/ Or even bothered to call me until they saw me on TV”. And some of the song’s most vicious lines were reserved for his mother, who was in the process of suing him for $10m in the wake of The Slim Shady LP, claiming lines like “my mom smokes more dope than I do” as defamation.

Mathers claimed to be unsurprised at being sued by the “lawsuit queen”. “That’s how she makes money,” he said, although after two years of litigation she’d only make around $1,600 after lawyers’ fees decimated her $25,000 settlement. But with his detractors painting him as the misogynistic, violent and homophobic poster boy for the Columbine generation; his fans becoming intrusive; and mainstream stalwarts like Will Smith criticising him for his lyrical content at MTV Awards shows, to face legal action from his own family would have made him feel universally besieged.

Yet, despite playing her his musical murder fantasy, he also reunited with Kim and the couple married. So the Eminem that Mike Elizondo worked with during intense, month-long stints at a variety of LA studios, often during 20-hour sessions over two recording rooms (“it was a mini-factory,” Elizondo says) was as playful as he was haunted. “Some days he’d come in and he’s a big prankster,” he recalls, “very light-hearted, poking fun, little roasting sessions with the musicians and engineers. And then there were times when maybe something went on at home and it was a tougher day and he’d just channel it. You’d get some of the humorous side of Marshall and the more intense and serious sides. He channelled all sides of where he was at in his life.”

His determination not to back down in the face of criticism was evident from the very first track that emerged from these sessions. Eminem used “Kill You” to set Shady loose on his most obscene rampage yet. As Shady drugged, kidnapped and murdered women, ran amok with a machete and even raped his own mother, the track seemed designed to emphasise the ludicrous extremes of the character’s vile crimes and rebuff accusations that Shady was anything more than a slasher-flick fiction.

“The whole idea of this song was to say some of the most f***ed-up shit,” Eminem wrote in Angry Blonde. “Just to let people know that I’m back. That I didn’t lose it. That I wasn’t compromising nothing and I didn’t change. If anything ... I got worse.”

Did he assume the Slim Shady character while recording? “Not really,” Elizondo says. “There are so many artists – Bowie creating Ziggy Stardust, or even Prince – who create these alter egos to give them the licence to go crazy and do something they maybe wouldn’t do normally. There was never any discussion of ‘I’m doing this song as this character, that song as Eminem’. Any time he was saying something insane you realised he was tapping into the Slim Shady character.”

How much of Shady was in him? Was he a provocative joke on the listener or was there real anger and brutality there? “I think Em’s all of those things,” Elizondo says. “There’s a side to him that’s very light-hearted and hilarious, but there’s part of him that’s got the temper. He had too much riding on what he had hoped to achieve that he wasn’t going to allow anybody to say anything negative about him without coming back and coming back viciously, not to just hurt them but literally end careers. So there was a temper but he channelled it in an artistic way rather than going out doing anything to cause anyone harm physically. He did it on record.”

Elizondo remembers the mentality of the sessions as being “let’s aim for making a masterpiece” and “to establish it wasn’t a fluke ... There was a lot of expectation to try to surpass what he did on that first record.” Key to that ambition was the arrival of a particularly ardent fictional fan. “I vividly remember him coming in and playing this song off of the Gwyneth Paltrow movie Sliding Doors,” says Elizondo, “and Marshall’s going, ‘I’ve got this idea to reuse this hook,’ and that went on to be ‘Stan’.”

The “Stan” beat, which defiled a verse from Dido’s saccharine soul tune “Thank You”, had been sent to Eminem by producer The 45 King. “When I heard ‘your picture on my wall’, I was like, ‘Yo, this could be about somebody who takes me too seriously,’” Eminem wrote on RapGenius.com. He immediately envisioned a series of letters from an increasingly deranged admirer, culminating in Stan murdering his wife and killing himself in a copycat tribute to “’97 Bonnie & Clyde”. “Stan” wouldn’t just form the atmospheric core of The Marshall Mathers LP, with its ominous thunderstorms and skilfully plotted dramas and twists, its legendary protagonist would become the modern-day byword for obsessive fandom.

Not bad, considering Eminem was furious that a stoned engineer accidentally wiped his “way better” original take of the car crash scene. Although the track was improved by missing out the proposed Halloween-style final verse. “There was a verse where [Stan] got out of the water,” Eminem told SiriusXM radio. “He escaped and came to my house to kill me. Then I had to kill him first, [but] I missed him, and he was in the hospital for three weeks. Then he was pissed off that I didn’t write him get-well cards, so he came to kill me again, and in the last verse, finally, I just blew his head off.”

Though “Stan” would eventually give Eminem a UK No 1, when he delivered the album to Interscope the label didn’t feel he had a strong enough first single. They wanted another catchy shock-fest a la “My Name Is”, but Eminem instead turned in “The Way I Am”, a glowering, defiant diatribe about fan, media and label intrusion, and murder rap as catharsis for all that stress. It included some lines pointedly aimed at Interscope: “I’m not Mr NSYNC ... I wish that I would just die or get fired/ And dropped from my label ... I’m not gonna be able to top a ‘My Name Is’”. “[It] was the complete opposite of what they requested,” Eminem wrote in Angry Blonde. “I was kinda rebelling against the label by letting them know they couldn’t force me to do something that I didn’t want to do.”

Ironically, he was able to top “My Name Is”. “I remember Em was getting to this point where he didn’t know that he had any more songs in him,” Elizondo says. “Everyone’s searching for that first single, at this point that’s the game. The album’s done, you think you’ve got the first single but let’s see if we can beat it, get something even catchier or hookier. Jimmy [Iovine, CEO of Interscope], was pushing, saying, ‘We’ve got two more weeks, let’s see what comes out of it.’”

With just hours to go before the final deadline, they produced “The Real Slim Shady”, a throwback to the effervescent, celeb-baiting savagery of the previous album. Amid lines dissing Will Smith, Tommy Lee and Christina Aguilera (Eminem suggested improprieties between Aguilera, TV host Carson Daly and Limp Bizkit’s Fred Durst, in retaliation for Aguilera having made public the news that Mathers had married Kim), the track acted as a call-to-arms for the Shady nation. “Every single person is a Slim Shady lurking,” Eminem rapped, painting his evil alter ego as a universal free spirit, “be proud to be outta your mind and outta control”.

The world stood up. “A powerful, thought-provoking portrait of the psychopathology of antipathy,” wrote The Independent. “The Marshall Mathers LP is a car-crash record: loud, wild, dangerous, out of control, grotesque, unsettling,” wrote Rolling Stone. “It’s also impossible to pull your ears away from.” “The Real Slim Shady” shot to No 1 in the UK and became his first US top five hit in April 2000. In its wake, The Marshall Mathers LP was a phenomenon, topping charts across the world. It was the first rap album to sell a million copies in the US in its first week and the second fastest-selling American album ever – although it must have stung a little that it was beaten, just months earlier, by NSYNC’s No Strings Attached.

“It was a perfect storm of controversy, humour and outlandishness,” Elizondo argues, but it buffered Eminem too. Jazz musician Jacques Loussier would sue for $10m, claiming that the beat to “Kill You” was lifted from his track “Pulsion”. The same track’s relentless imagery of violence against women was cited by Lynne Cheney at a US Senate hearing as contributing to America’s culture of violence, and by Ontario attorney general Jim Flaherty as a hate crime when he tried to stop Eminem entering Canada to play the Toronto SkyDome. Accusations of homophobia from LGBT+ groups led to Eminem displaying his gay-friendly credentials with a duet of “Stan” with Elton John at the 2001 Grammy awards.

And, inevitably, such a dark supernova had nefarious fallout. Mathers would admit in his autobiography that he “went through a phase back then when I was f***ing shooting pistols in the air behind the studio and ... pulling guns on motherf***ers, pointing a pistol in somebody’s face, not even realising that I could’ve gone to jail for that shit”. One of the people at the other end of his barrel was Insane Clown Posse associate Douglas Dail, whom Mathers threatened with a gun in a parking lot in Royal Oak, Michigan, on 3 June, 2000; the next day he was arrested for allegedly pistol-whipping a man, John Guerra, whom he believed he saw kissing Kim outside a bar in Warren. Both incidents resulted in lengthy probation orders, and the personal impact was even greater. Kim attempted suicide by slashing her wrists on 7 July and the pair legally separated in August, divorcing the following year. Kim would also sue Mathers for defamation over “Kim”, settling out of court, although that wouldn’t mark the end of their on-off soap opera.

In terms of proving himself, however, The Marshall Mathers LP was a resonant triumph. Uncompromising and groundbreaking, its cinematic atmospheres and fervent ambition made it a horrorcore benchmark, regularly ranked amongst the best rap albums ever made. “There’s a lot of substance and a lot of things that were straight out of his life,” says Elizondo. “From beginning to end, we weren’t just trying to have a big song on the radio, everybody who was involved wanted to make sure that this record was a masterpiece and take every opportunity to perfect it. I still think it holds up sonically and artistically. It was a snapshot of that period of music as well as that period of the world.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks