Festival Nacional del Malambo: The Argentinian competition where winners are treated like demigods

It’s a spectacle Leila Guerriero felt she had to see for herself

On Monday 5 January 2009, the Argentinian daily La Nación ran an article in its arts supplement, written by the journalist Gabriel Plaza, with the headline: “The folk athletes line up”. Comprising two small columns on the front page and two medium-sized columns a couple of pages in, it included the following lines: “Considered an elite corps within the world of traditional folk dance, past champions, on the streets of Laborde at least, are treated with all the respect of ancient Greek sporting legends.” I hung on to the article, and then found that years had elapsed and still I was thinking about it. I’d never heard of Laborde before, but once I’d read this piece of red-hot information, the joining together of elite corps and sporting legends with traditional dance and a town in the middle of nowhere… I couldn’t stop thinking about going and seeing for myself.

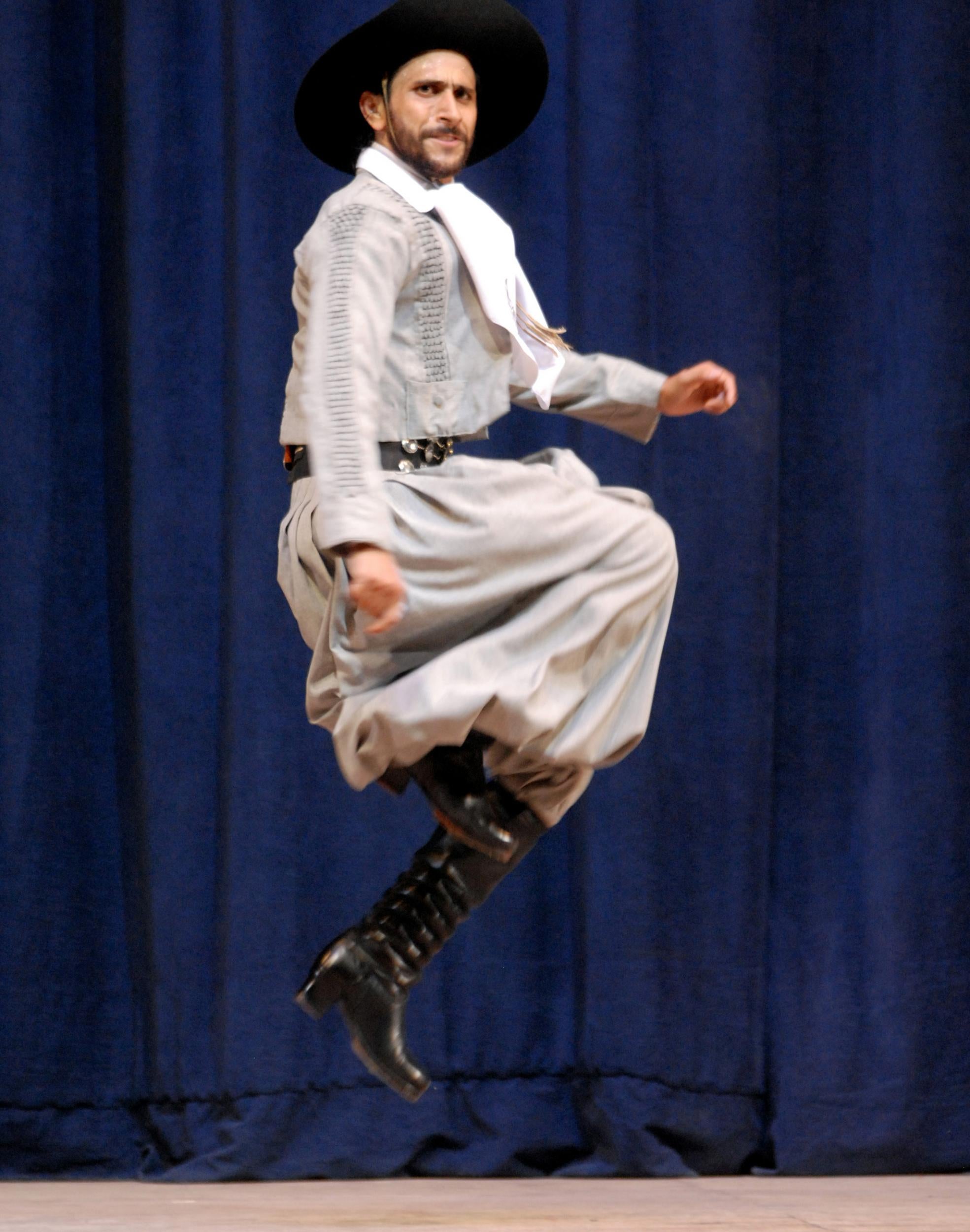

Malambo consists of “a joust between men who take turns to dance to music”. A dance the gauchos would challenge one another with, trying to best their opponents in feats of stamina and skill. Its origins are unclear, though people agree it probably arrived in Argentina from Peru. Sets of tap dance-like movements, each associated with a certain musical metre, combine to form the “figures”. Composed of taps of the toes, soles and heels, pauses on the balls of the feet, and lifts and twists of the ankles, a malambo performance at the highest level will include more than 20 such figures, divided up by repiqueteos – toe taps at a pace of no fewer than eight per second – requiring enormous responsiveness in the muscles. Each side has to be mirrored, a right-foot figure immediately repeated, identically, with the left foot, so that a dancer of malambo needs equal precision, strength, speed and elegance on both sides.

This strictly masculine dance, which began life as a crude kind of gauntlet-throwing, had by the 20th century been strictly choreographed into performances lasting between two and five minutes. Though best known for the versions seen in “for export” spectacles – including hopscotch between candles and the juggling of knives – some traditional festivals in the country still stick to malambo’s essence. But it is in Laborde, this town in the middle of pampas flatlands, where malambo in its purest form is preserved: since 1966 a prestigious and formidable six-day competition has been held here, one that places fierce physical demands on the participants and concludes with a winner who is given the title of “champion”.

Unlike the festivals in Cosquín and La Sierra, malambo is the only featured dance in Laborde; and, also unlike other venues, where two or three minutes is the allotted time, here the dance lasts for five minutes. Now, five minutes is hardly an eternity. A negligible amount of time when compared with a 12-hour flight, a mere breath in a three-day marathon. But not so if the right comparisons are applied. The fastest 100-metre runners in the world aim for sub-10 second times. A malambo dancer in full flow moves his feet just as quickly as a 100m runner, only he has to keep it up for five minutes. A malambo dancer’s preparation therefore involves not only the sort of artistic instruction a ballet dancer would undergo, but also the physical and psychological preparations of an athlete. They don’t smoke or drink, and they never go out late. Long-distance running and time in the gym are standard, and the aspiring malambista also has to work to perfect his concentration levels and develop the correct attitude: a keen sense of conviction and self-confidence is vital. Though some train alone, most employ a coach, usually a past champion, at considerable expense.

Add to this the gym membership fees, the consultations with nutritionists and sports scientists, healthy food, and of course the attire – which can cost up to $800 (£530) for each outfit. A pair of the norteño boots alone costs $140 – and, given the punishment they receive, needs replacing every four or six months. There is also the annual trip to Laborde itself, which often means a stay of two weeks. Most of the contestants are from working-class families. The more fortunate give dance classes, but there are plenty of part-time electricians, bricklayers and mechanics among them. A few will win the first time they enter, but for almost all it is a question of coming back, year after year.

As for prizes, winners can expect neither cash nor a holiday, neither a house nor a car, but simply a rather plain trophy crafted by a local artisan. Laborde’s true prize cannot be seen with the eyes: uppermost in everybody’s thoughts are the prestige and recognition, the endorsement and respect, and the huge honour that comes with being one of the best among the select few even able to perform this murderous dance. In the small, courtier-like circle of traditional dance devotees, a Laborde champion becomes a demigod.

And yet… in order to preserve Laborde’s prestige and affirm its elite nature, a tacit pact has been in place between Laborde champions since the festival’s inception: though they may go and compete elsewhere, they may never enter the Laborde festival again, or dance the solo malambo at other festivals. Should anyone break this pact – there have been two or three exceptions – they’ll suffer the contempt and scorn of their peers. So the malambo a man dances to win will also be one of his last: the summit scaled by a Laborde champion is also the end.

In January 2011, I went to Laborde with the simple plan of telling the story of this festival, and of trying to understand why people take part in such a thing: fighting your way to the top, only to come straight back down again.

Backstage, in a space with an untiled floor and hollow brick walls, stand the changing rooms. Four of these are monastic cells with sheet metal doors and a single cement table inside, nothing more. The fifth is off in one corner, with a gap between the top of its walls and the ceiling, and in this case with no table and no light of its own. There are two toilets whose doors don’t shut properly, and a long mirror lining one of the walls. The eye-watering aroma of muscle balm fills the space, a hive of comings and goings, people in various states of undress, putting make-up on, stretching muscles, applying sprays, braiding hair, trimming beards – all of them on edge, waiting. There are numerous clothes racks bearing dresses and gaucho costumes, there are men in underclothes, and women demurely manoeuvring bras off or on. In advance of their stage-calls, dozens of people do their warm-ups as the adrenaline pounds, blasting electricity into their inflamed hearts.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

“No, I can’t get it off, idiot. This ring! I’m gonna kill myself.”

A girl with impeccable braids, wearing a charming flower print dress with voluminous shoulder ruffles, is wrestling with an enormous, fuchsia pink ring. One swollen finger, and five minutes before she’s due to dance. The ring would mean automatic disqualification.

“You’ve used soap?”

“Yes!”

“And your spit, and washing-up liquid?”

“Yes, yes, it’s not coming off!”

“Ninny.”

On a bench to one side, a young guy is using a plastic bag to help slide his foot into his pointed-heel boots. “It’s to make them slip in,” he says. You can’t do it otherwise. We always use boots two sizes too small – it gives us better control to have them so tight.”

On the floor in front of the wall-mirror is a long wooden plank. Four dancers, the members of a norteño quartet, are standing side by side on the plank, jutting out their chins and rehearsing haughty, defiant glares. Four chests rise up like the breasts of four cockerels preparing to fight. What follows resembles nothing so much as a section of the North Korean army on parade: astonishingly synchronised strides, and eight heels catching, stamping and scraping the floor – as though they were one single heel. An interested circle forms around them, other dancers quietly contemplating the moves. When the quartet comes to a stop, there’s a sudden, frozen moment of rapture, before the circle disbands – as though it had never been there, as though what just happened was a sacred, or secret, ceremony, or both.

An hour later, at midnight, the doors to the five changing rooms are all shut and, on the other side of these battered metal sheets, noises can be heard, now drums, now guitars, now the most unalloyed of silences. There, standing to attention, are the men that all of Laborde is waiting for. Five of the dancers in the Senior Soloist category. “So much goes through your head.” “You feel so many different things.” “You never forget it.” “You have to go up there thinking of yourself as champion.” “To represent my province is already success for me.” “People say the most amazing things to you.”

The way the malambistas talk is somewhat similar to professional footballers when they speak to journalists: “We’ve got a great group.” “Team spirit is amazing.” “They were the better team.” When it comes to specific questions – what do they think about while they dance, what memories do they have of the night they won? – they all come out with the same set phrases: they make reference to the huge amount that goes through their heads, or to how wonderful it all was, but rarely will they go into specifics. If someone pushes them to describe at least one of the wonderful things that happened to them, they’ll tell the story of how, for example, the champion from 1996 came and gave them a hug and said, “Now you have to show you’re worthy of that trophy”; or about the little child, in a school in Patagonia, who trembled with emotion on being given an autograph. Maybe these things seem insignificant. For them – children from large families, raised in remote villages, living in the most strained economic circumstances, and with no famous forebears – such things mean everything.

If the daytime temperature can rise above 40˚C, it also drops at night without fail. Today, a Friday, at half-past midnight, it must be around 13˚C, but backstage it’s carnival time. There are half-dressed bodies, sweat, music and the sound of corridas being sung, the ubiquitous ballad songs. The La Rioja representative, Darío Flores, descends the stage in the usual manner: his vision blurry, his body crucified, he stares around, keeping his arms outstretched to encourage air back into his starved lungs. Someone hugs him, and he, seemingly coming out of a trance, simply says: “Thank you, thank you.” Then I hear a guitar being strummed out on the stage. The notes contain something – something akin to an animal inching along low to the ground, about to pounce – that grabs my attention. So I hurry back out, crouching as I go, and take a seat behind the jury.

It’s my first sighting of Rodolfo González Alcántara. And what I see strikes me dumb.

Why, if he was like many of the others? Beige jacket, grey waistcoat, one of the wide-brimmed hats – the chiripá – in red, and a piece of black cord for a tie. And why, if I didn’t yet know the difference between a very good dancer and a mediocre one? But there he was: Rodolfo González Alcántara, 28 years old, representing La Pampa, towering over everyone – and there I was, sitting on the grass, speechless. When he finished his dance, the announcer declared in her deadpan voice: “Time: four minutes and 52 seconds.” And that was the precise moment when this story became something else. A not-at-all simple story. The story of a common man.

When Rodolfo González Alcántara came on that Friday evening, he moved to centre stage like a strong wind or a puma, like a stag or a thief of souls, standing still for two or three beats, frowning as he fixed his gaze on something behind us, something no person could see. The first movement he made with his legs ruffled his cribo trousers like some delicate underwater creature. Then, for the ensuing four minutes and 52 seconds, the night became a thing that he pounded with his fist: he became the countryside, the dry earth, the taut pampas horizon, he was the smell of horses, the sound of the sky in summer, and the hum of solitude. Fury, illness, and war, he became the opposite of peace. He was the slashing knife, the cannibal and a decree. At the end he stamped his foot with terrific force and stood, covered in stars, resplendent, staring through the peeling layers of night air. And, with a sidelong smile – like that of a prince, a vagabond, or a demon – he touched the brim of his hat. And was gone.

And that was it.

This is an edited extract from ‘A Simple Story: Dancing For His Life’ by Leila Guerriero (£9.99, Pushkin Press), out now. Translated by Tom Bunstead.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks