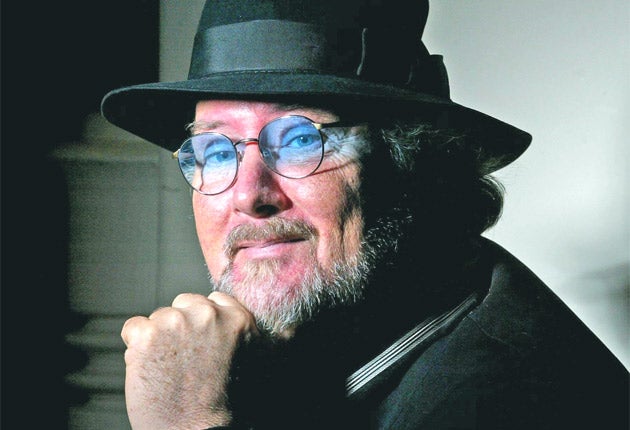

Gerry Rafferty: Bipolar alcoholic, industry misfit – and one of Britain’s most treasured musicians

Ten years after his death, a new record adds to the treasured artist’s legacy. Paul Sexton speaks to Rafferty’s daughter Martha about putting together one final round of superior song craft

The scorecard of one of British music’s most treasured artists and saddest losses has just undergone a recount. The 10 solo albums made by Gerry Rafferty during his lifetime form a distinguished legacy, from 1971’s cult favourite Can I Have My Money Back, through the platinum-selling years of City to City and Night Owl, to later, less-celebrated gems such as North and South and On A Wing And A Prayer. Ten years after his death, eerily but joyously, there’s now an eleventh.

Rest In Blue is a record as poignant as its title, a quintessential labour of love brought to fruition by the Scottish musician’s daughter Martha Rafferty. This far after his passing at a painfully early 63, the immediate temptation is to imagine the sound of barrels being scraped and material being furiously cobbled. But this is, broadly, the record he was making until a few months before his death from liver failure, and the feeling that emanates from it is the love for him from those who completed it, and the happy surprise of one final round of Rafferty’s superior song craft.

That talent was repeatedly endorsed over the years by the likes of John Peel, Paul McCartney and Paul Simon, who expressed the wish that he’d written Gerry’s first hit in his days with the excellent Scottish band Stealers Wheel, “Stuck In The Middle With You”. More recently, no less a modern figurehead than Harry Styles said on Later... With Jools Holland that he felt the same way about “Right Down The Line”.

Now there are some hugely welcome additions to that songbook. “This was the majority of the songs he’d been working on as his next album,” says Martha, a plain-speaking Scot who understands there may be a certain scepticism about a “new” record by her dad. When he died, the world lost a superb singer-songwriter, but she lost a father, a self-confessed bipolar alcoholic and industry misfit, who despised the machinations of the business so much that he walked out on a US tour at the height of his success.

“I knew that at some point I would want to return to what he’d started and see if there was a way to bring it to fruition,” she says. “I actually put a home studio together in 2012, and I got Andy Patterson, the engineer, up to Scotland, but I couldn’t do it. I just wasn’t ready emotionally. It was too difficult. I even along the way suggested it to a few other people, but for some reason there just wasn’t the right time or place or person to say, ‘Yes, let’s go for it.’

“Somehow lockdown was the key to everything,” Martha goes on. “Emotionally, I was ready. It was the 10-year anniversary of his death. Bereaving is a weird, non-linear process, but somehow 10 years just felt like the right amount of time to be able to turn back and pick it up.”

Martha went into the studio with vocal recordings by her father in various stages of completion. Stripping many of them back to basics and unafraid to paste together the best parts, often years apart in origin, she then called in guitarist Hugh Burns, Gerry’s wingman of many years, as well as seasoned vocalist Katie Kissoon, former Dire Straits keyboard player Alan Clark, and rising London-based producer Tambala. A 1990s painting that Rafferty bought and had earmarked for the sleeve by John Byrne, whose work (signed as Patrick) illustrated Gerry’s music from Stealers Wheel onwards, is indeed the cover art.

“For everybody who’s worked on it, it’s been a really emotional process,” says Martha. “Andy Patterson had been working with him on the record since 2006-2007, so he’d been there from the beginning. A lot of the musicians he’d worked with over the years remembered recording various parts of the tracks. [Gerry] always had a home studio, and Andy was coming to work with him daily until about eight months before he died.”

The result, somewhat supernaturally, is not only cohesive, but brings out sides of Rafferty’s musical personality that reach beyond the formidable charms of “Baker Street”, “Night Owl” and “Get It Right Next Time”. Rest In Blue offers the top-notch pop-rock of “Sign Of The Times”, “Slow Down” and others, but also shines new light on his skills as a folk traditionalist.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

There are elegant versions of the time-honoured “Wild Mountain Thyme” and “Dirty Old Town”, as well as Richard and Linda Thompson’s “It’s Just The Motion”. The album concludes with a rootsy remake of “Stuck In The Middle With You”. “It’s really nice to hear him singing that song with a mature voice,” says Martha.

Billy Connolly, his pre-fame pal from their days together in the Humblebums, is quoted as saying, “I’ve never heard Gerry sing so well. He never fails to amaze me.” His thumbs up meant a lot to her. “I sent it to Billy in the beginning, because I really wanted him to hear it,” she confides. “He really enjoyed it, particularly ‘Wild Mountain Thyme’. It brought a tear to his eye, he said. I think that’s the one song that [for] people who know him well, really touches the heartstrings, because they’ll have heard him singing those traditional songs at parties and gatherings. So it’s probably the most personal, in a way.”

Rafferty took great pride in being able to sing well, Martha continues. “People don’t know that one of the influences in the pot, along with the folk music, the hymns from his Catholic upbringing and rock ‘n’ roll, was Frank Sinatra, and that era of performance and production. He really aimed for that kind of polished, professional sound – that really spoke to him.

“When you grow up on the west coast of Scotland, performing well vocally in front of your peers and your family is really important. We all had to do that growing up. We all had to sing and take our turn round the table at Christmas. You had to be able to sing in harmony and understand the structure of it and be able to sing together. He took all that very seriously. Some of the happiest memories of my life have been us all singing together, for sure. Beatles tracks, Everly Brothers, a lot of traditional stuff, the Bothy Band, the McGarrigles.”

Martha witnessed all too closely how her father’s success was a sword with sharp edges. She was born in Tunbridge Wells, where Rafferty was living when Stealers Wheel were a touring band. “I was eight years old when City To City went as big as it did, and it was just weird,” she says. “We lived in a street, we had neighbours, and the more famous you got, the more you’d retreat from other people.

“So the houses and the gardens got bigger, the distance to other people got further, and people’s attitude changes. You start to become aware that people who didn’t care suddenly care a lot. I was very wary of all of that as a child, and I probably still am. If you’ve got money, the natural thing to do is to buy a bigger house, isn’t it? So you do become more isolated. Money isolates and separates people, and I don’t think it’s a particularly healthy thing.”

Rafferty craved anonymity. “He often said he really valued being the observer. Once you become too famous, you become the observed, which for him was a definition of hell, really, not to be able to walk around freely.”

That dissatisfaction would manifest itself when Rafferty “made it” as a solo artist in America. “He was due to tour the US, and he’d gone out there to do a lot of press,” says Martha. “He was met with the full showbiz trappings, a big limo from the airport, a suite on Central Park, invited to all the parties. And he had a panic attack in the streets of New York, and thought he’d had a heart attack.”

Such was his discomfort with being the centre of attention on that trip, he took the sort of decision that gives music executives palpitations. “It was so far removed from who he was that he decided at that point that that just wasn’t the right path for him,” Martha goes on. “So he took a big step back and pulled out of his tour, much to the frustration of his management and his record company, I’m sure.”

It was, she believes, an act of self-preservation. “That just wasn’t his world. He needed a certain degree of peace and stability and quiet around him to work. He saw the casualties as well, particularly the children of a lot of these famous people, and he didn’t want that for our family. I’m grateful in a way that that wasn’t the atmosphere I grew up around.”

The album begins with not one but two unflinching descriptions of Gerry’s alcoholism and depression, in the upbeat “Still In Denial” and the haunting “Full Moon”. “He wasn’t under any illusions about the fact that he was an alcoholic,” says his daughter. “He sought treatment and went into detox many times, at these horrendous clinics that exist. So he was in and out of that for many years. He felt in some ways that’s what he had inherited, because his father was an alcoholic, and so on, probably through the generations.”

The impact of his drinking was insidious, but undeniable. “It wasn’t really a problem in the beginning,” Martha reflects. “Everybody drank. But I think he drank for specific reasons, which was in connection with his mental health. He was bipolar, and he’d struggled with episodes of depression. Drinking helped him find an even keel through all his responsibilities as a performer, and it helped until it didn’t help anymore. His peers, like Rab Noakes and Billy Connolly, all drank as well, but they were able to stop, because I don’t think they had the same underlying issues.”

As she says, men of Rafferty’s generation simply didn’t discuss mental health. “There’s so much judgement around addiction, and a lot of blame that it’s down to willpower, and people’s demons getting the better of them, all this nonsense,” Martha says with quiet forcefulness. “All this ridiculous rhetoric that’s bandied about. ‘People’s demons’ – what does that even mean? And ‘what a tragedy,’ but no one chooses the way they die. Addiction is a disease like any disease, and that’s what he died from. It’s not a pleasant thing for anyone to go through or to witness, but he still achieved a great deal in the time he had, and I think that’s enough.”

Thus, a decade after his passing, we have fresh memories of a marvellous singer-songwriter, and further evidence, as he once wrote, that whatever’s written in your heart, that’s all that matters. “I really wanted this album to reflect what I’d grown up hearing, which was him with the guitar or the piano, singing, without any other accompaniment,” concludes Martha. “That’s the real test of a person’s talent, and it was just so beautiful. Everyone who’s heard him like that realises how great he was, and I really wanted to try and capture that.”

Gerry Rafferty’s Rest In Blue is released by Parlophone on 3 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks