Interpol explore the inner Marauder on their upcoming album – interview

American rock trio discuss their upcoming sixth record ‘Marauder’, the changing New York music scene, and why they chose a former US attorney general to star on their album cover

Just after the second chorus of Interpol’s new single “The Rover”, guitarist Daniel Kessler sounds as though he’s losing control of its central riff, before reining it back in again. It’s one of those moments in a song that sticks with you and fits the track’s character of this wayward, pirate-like figure that appears on several occasions in the American rock band’s upcoming sixth album, Marauder.

Kessler has to be one of the sharpest-dressed men in music. A few days after this interview he’ll appear onstage at BST Festival in Hyde Park as the band support headliners The Cure, looking as though he just stepped off the catwalk for Armani or auditioned for the next James Bond movie, and somehow not sweating despite the 30-plus-degree heat.

It’s a far cry from when they recorded Marauder – their first album since 2014’s El Pintor – set up in subterranean New York in the midst of winter. Classically sparse, rich guitar from Kessler’s Epiphone Casino; dark, cool vocals from frontman Paul Banks and intricate, snare-heavy drums by Sam Fogarino make it one of the band’s best, where they welcomed an outside producer for the first time since 2007’s Our Love to Admire, in the shape of Dave Fridmann (Mogwai, The Flaming Lips, Sleater-Kinney, Spoon).

“I think we had a good, fruitful writing period together,” Kessler says now, at the band’s hotel in London’s West End. “Right away I think we felt a lot of energy bouncing off the walls. When we’re working on something, the songs have to have a life already… we’re not one of those bands who waits to go into the studio to write the middle section.

“Maybe it puts a little pressure on us, but that’s the way we’ve always been. I think Dave got a good sense of what we were doing when we were making these rehearsal recordings… that was when he wanted to record everything onto tape. He sensed it was quite lively and quite raw, and he was happy with our direction, and I think we also were very mindful to think before we speak, to leave space… to not give a ‘but’ when he was offering something, and I think we benefited from that.”

Throughout Marauder there’s a kind of tension, as though the band are a coiled spring. Part of that seems to stem from Fridmann’s recording process where he committed music to tape, lending an analogue warmth to the band’s traditionally cool sound, but also forcing them to make snappy choices.

“It was like having my safety net taken away,” Kessler admits. “In the studio we adjusted to that style of recording and moved forward with each song. We had a kinship, Dave included, and it had a good energy. There could be flubs, but if we liked them then we’d keep them in. It’s human, there’s a personality to it, highlighting our imperfections… but in a good way.”

Unlike other bands who have migrated to LA or Nashville, Interpol have always seemed at home in New York, but aren’t really sure if there’s anything specific that still “binds” them to that city.

“It’s pretty ever-changing,” Fogarino says, joining Kessler at the table and pouring a glass of water. “It’s seemed to follow this cycle since the Sixties, since there were ‘scenes’ coming out of New York: pop music, rock music, the Andy Warhol times merging into early CBGBs, Max’s Kansas City… then coming around most recently to the early 2000s. And there are different opinions on what changed during those periods and how the city changed, the perception of what was gentrified and what was still standing in integrity.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

“I think New York is just where we work,” Kessler shrugs. “Paul and I live mostly there, but I think we could write anywhere. New York has become a lot more expensive, less of this artistic, fertile playground… you can’t really afford to live there unless you’re killing it. Also, a lot of people just move to LA, in the last 10 years.” He offers a self-knowing grin: “It’s having a moment.”

Fogarino, who joined Interpol a few years after the band’s formation in 1997, shines on this record, driving beats that appear simple at first but, when you pay closer attention, turn out to be more complex and multi-faceted; a style that sounds loose and frenetic but is tightly controlled in reality. He draws on old favourites for influences rather than anything new.

“It’s kind of hard to enjoy something while you’re recording, and I don’t battle for originality; I just try to serve the song as best as possible,” he says. “There are certain points to get rhythmical impetus and it’s usually something really old, or something that I love – that I’ve either never borrowed from or something that I always do.

“A lot of R&B, Stax or Motown, Bill Withers or older Otis Redding… it’s so beautifully simple, and so complex at the same time, because it’s not about the thing you’re playing but how you’re playing it,” he adds.

They both laugh at the mention of that off-kilter rhythm on “The Rover. “Very intentional,” Kessler says, eyes twinkling. “Yeah, it’s like Sam and I are staggering it out a bit.”

“Some things would be on a metronome, and some things would depend on the more natural – ‘speeding up and slowing down’ – the more emotional performance,” Fogarino says. “And other things were kept more logical.

“On ‘The Rover’ it’s this beautiful anticipation, that’s why Dave kept us off the click for a song like that, because it’s not a mistake… it’s an articulation of the moment.” He looks at his bandmate, jokingly assuring him: “I’m not trivialising it, Daniel, and I’m not trying to speak for you, but I’m empathising with that and the nature of the guitar being able to do that… the whole idea of being off the grid, and you being loose enough.”

Kessler nods. “We were very well rehearsed but there were tracks where we’d get rid of the click or make something faster. Usually you might overexaggerate it, but I think we weren’t over-thinking it too much, we were just playing together as well as we could, and it fed us into a really good rock’n’roll take. It wasn’t a very rigid recording process, but I think at the same time we were playing tightly together.”

In a way their approach is very similar to those old Motown or Led Zeppelin records Fogarino loves – where you hear moments that may not have been intentional but make the music all the more special for them.

“Totally, and how could that not be an inspiration?” Fogarino says. “There are no overdubs, it’s all one take with maybe a little separation, and that’s just beautiful. You’re being inspired by performances, and they’re all interconnected, like the drummer doing a little stutter which leads to the guitarist sliding into a note… the many things that just transpire as a live performance.

“There’s something on a personal level, there’s a beauty to how it’s aged. It creates its own filter. And once you get past that dreamy aspect you’re listening to the performance. It’s almost taking music out of the genre. Good chord progression, or something unique that happened in a Diana Ross song… it transcends genre at that point.”

Banks arrives soon after Kessler and Fogarino leave to do another interview. He comes across as a little wary at first, or just expectant that an interview is always conducted with the intention of getting “an angle”. But he warms up quickly: especially when he’s debating the merits of Drake’s back catalogue and whether his latest album Scorpion is any good. And when he talks about how good Beck is – “I’m happy that I’m remembering more to talk about how much I love Beck,” he says.

He contradicts himself a lot, beginning to state that while his lyrics may sound isolated in a reflection of their environment, he actually wrote them on a beach in Panama. “You know what though? Here’s the real way the process happens,” he says, changing his mind halfway through the sentence.

“The core seeds of all the songs were written in the basement, so that was the claustrophobic space, actually. Then I’d come up with the top line and a core concept, and now I’m good, and then I’d go to the beach and write that out… Those memories of cold were still in my mind but I was, y’know… warm,” he concludes with a laugh.

The “marauder” on the record is the part of Banks that could get up to “all kinds of shenanigans” – the 40-year-old admits he used to go pretty hard. “I think it’s part of a rich, full life to let that part of you be in the driver’s seat at times,” he reasons. “I look at my inner marauder as a source of fuel, and sometimes you can shoot it out in sort of useless or chaotic ways.”

“You have that cartoon in the UK, the Tasmanian devil, right?” he asks, twisting his hands to demonstrate the movement. “He was this flurry, a blur, and that’s how I picture my marauder these days. If you can harness him to… build bridges or plough the land, so to speak, rather than just knock everything down, then he can become a great asset. That’s kind of how I see it.”

The “rover” on the title track isn’t him, though. Rather, it’s one of those “more tangential offshoots” that doesn’t reflect any compulsion to begin a cult. Banks is fascinated by that character. Those flaws or quirks of human nature are present as deep as the recording process of the album itself, something he says is actually called “destructive recording”: “If you f**k up your guitar, and you want to jump back in where you f**ked up and you start recording the second time, you’re erasing what was there.”

With ProTools the band had the choice to layer each take and go through and take which part was best. But “destructive recording” forced them to be much more committal than some bands, forcing them to work “off the cuff”, and accept the blemishes, even embrace them.

“If you listen to Led Zeppelin now you realise there’s loads of imperfections there, and that makes it stand out,” Banks says. “There’s a human tendency when you have access to making something perfect, to make it perfect. Sam’s a fascinating drummer, because you watch him play, and it’s like you don’t really notice him doing a lot. But when you actually listen, it’s like… damn. There’s a whole counter-melody happening just with the opening on the hi-hat for ‘The Rover’.”

“You wanna hear the craziest thing that happened with Fridmann?” he asks, suddenly. “Do you have time? It was the first day we worked with him, and I felt like he was doing some Jedi s**t on me. We get in the live room and we have headphones on, and we’re tracking a song so I’m playing bass and probably singing scratch vocals to signal Daniel, and in my headphones, I start hearing the a capella vocals to someone else’s song, while I’m playing.

“And the craziest thing was that it was a really good take, but it was just some dude singing another song, in my headphones. And I played the whole thing, and I was looking around like ‘do you guys have any idea what’s happening to me right now?’ It was like my brain was being torn in two different directions. Anyway it turned out that they’d f**ked up with the tape and it was the band they’d done prior,“ he says, laughing. ”But I got through the f**king tape, pulled my headphones off and was like: ‘Yo Dave Fridmann’s f**king crazy man! This is heavy!’“

He loves that Interpol are a New York band, even though he wonders if it can still be considered the “city of music” anymore: “Because of the venues and the underground nightlife scene… I feel like you’re always going to attract talent, and they’ll find a way, but it could just as easily now appear anywhere else,” he says.

“In Mexico City where we did the press conference, there was this camera guy and he had this Menzingers T-shirt [a punk band from New Jersey]. It was a really cool logo and a cool shirt, and I was like, f**k, I live like 20 miles from there and you’re in Mexico City…! But Mexico City’s always been cool like that,” he adds.

On the lyrics sheet that was sent out with an album stream ahead of interviews, one song didn’t appear on the album itself – Kessler and Fogarino had confirmed earlier that they decided to remove it from the final version.

“The beauty of having confidence in your management and your label is that… no one was questioning if we liked that song or not,” Banks says now. “It’s just like, does this record need one more song?”

He smiles at the suggestion that Drake could have used a similar tactic on his latest album. “I’m enjoying it,” he states, then with a grin, “but see, I’m his biggest fan. If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late, that was when I started being like… this f**king dude is amaaazing. Then I circled back and found ‘Worst Behavior’ and a couple of great songs on the previous release. Same with ‘Crew Love’ on Take Care.”

He prefers Scorpion to Drake’s 2017 mixtape: “There was a bunch of s**t on that record where I don’t feel it was nearly as good as If You’re Reading This. More Life was the first project by Drake where I was like…” he puts on a deep voice: “Skip! Definitely more than I am on Scorpion. Can you give me five songs that are f**king amazing on More Life, please?” He nods, satisfied at the silence that follows.

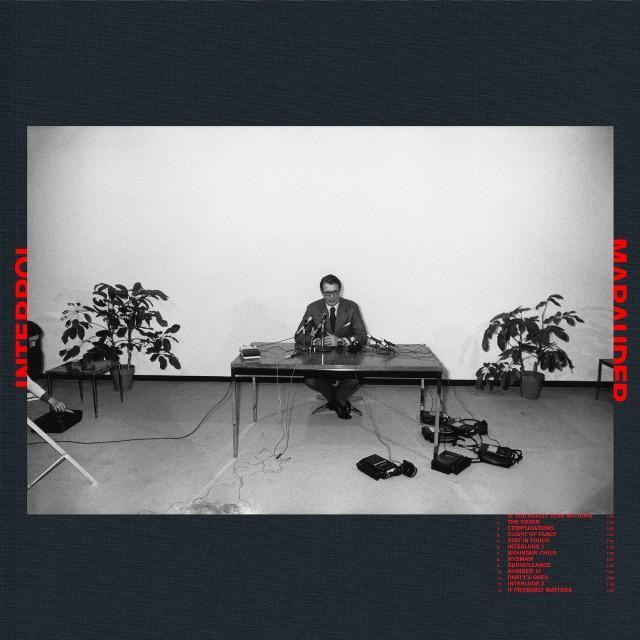

Marauder’s cover art is a photo taken by the storied American photographer Garry Winogrand: a shot portraying Elliot Richardson, the former attorney general famous for resigning after Nixon ordered him to fire Archibald Cox – the first special prosecutor named in the Watergate investigation.

“There aren’t many occasions where I’m stoked on something the other guys don’t like, so the album cover was a pretty unanimous decision as soon as we saw that picture with the layout our designers had put it on,” Banks says.

“Here’s the real dope,” he adds with a conspiratorial air, leaning forward. “I wanted to do this faux paparazzi photo from the Studio 54 era, and researching imagery from that time I found the nightclub El Morocco, which had Bogart and Sinatra sort of vibes with these zebra print banquettes…”

He was looking through photos of the club scene when Interpol’s designer found photos by Winogrand, which led to a deeper exploration of his work, and that’s when they stumbled on the Richardson picture.

“It was really an aesthetic choice, and I think the fact it has these beautiful, political overtones… there are lots of layers,” he says. “There’s the fact he’s sort of a hero because he refused to be bullied into going against his personal principles.

“Based on my writing, I like the isolation of the individual in that photo, that shot implies great strength but there’s a vulnerability too. I love that there’s a woman in the frame backing away...” he grins. “Like she just left meat out for a tiger.”

‘Marauder’, the new album by Interpol, is released on 24 August via Matador Records

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks