‘Utterly radical, subversive and alien’: the untold story of Irish post-punk

Bands like Fontaines DC are putting Ireland on the global guitar map but the island’s post-punk history is lesser known. Dean Van Nguyen speaks to the scene’s founding fathers, like SM Corporation and Stano, to find out why – and what U2 have to do with it all

Ireland has been enjoying a stirring surge of inventiveness among its guitar bands and a surge in post-punk urgency of late, forged in the tightly packed boulevards of its most sinful cities. There’s Fontaines DC, whose status as genuine worldbeaters has been solidified by a Grammy nomination to be settled next month. Critical darlings Girl Band and Murder Capital have also helped to put Irish post-punk on the map internationally, and there’s a clutch of young groups who are looking to follow the same path: Slow Riot, Robocobra Quartet, Silverbacks, the list is as long as the digits of pi.

Lesser known in this emerging story is the first wave of Irish post-punkers who emerged from the punk scene in the early 1980s. They, in many ways, have prefaced and predicted their modern successors. The Irish punk tradition is written into the nation’s musical legend, but the legacy of Irish post-punk hasn’t always been as respected. Thankfully, the global impact of its stylistic offspring breeds fresh curiosity.

Cult Irish musician Stano is revered throughout the Dublin underground as a one-time punk. He has spent four decades funnelling what he believes are the core tenets of the culture into making experimental, sometimes testing, post-punk music. His recent focus has been a reissue of his debut album Content To Write in I Dine Weathercraft, and last September, Anthology, an 18-track collection spanning 1982 to 1994.

While checking out the press coverage of his reissues, Stano has been fascinated to see his name connected to young Irish stars. “I was trying to think why is that being referenced,” Stano says of reading the names of new artists in reviews of his own work, “and I think it’s that they have the punk spirit. I spoke in my own Dublin accent and I was writing poems,” he says, echoing Fontaines DC’s approach. “I didn’t really know what I was doing in the music. For me it was just a big adventure.”

“My aesthetic is still going on,” says veteran performer Steve Averill of the punk band The Radiators From Space and post-punkers SM Corporation. “The spirit of [that] music is still very much alive in Ireland and a lot of the current bands like Fontaines DC are expressing different aspects of Irish culture in a way that is seeming to get across to a large audience.”

Before post-punk, though, there was punk. Back in the 1970s, it was inevitable that Ireland would be drawn to the genre’s willingness to challenge the status quo. Grey, repressed Ireland, where even divorce was still outlawed and a generation, restless and alienated, was coming of age in an economic void that made youth rebellion not just attractive, but required. In Northern Ireland, the Troubles had made touring bands stay away from the cities. In their place, homemade punk thrived and has become part of local identity.

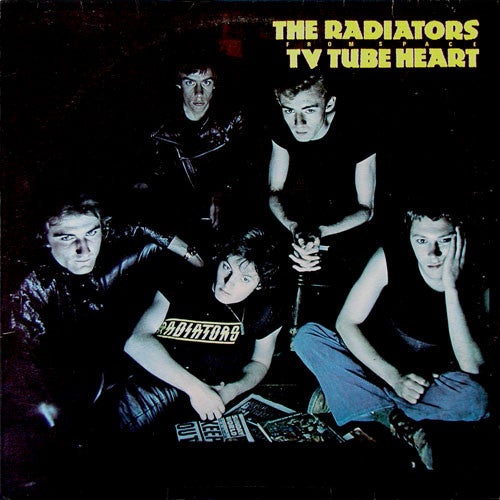

Irish punk doesn’t have an official starting point. In Derry, The Undertones began performing under the name in 1975 and are one of the most enduring artists of 20th century Irish music. Yet one band is regularly described as Ireland’s first punk outfit: The Radiators From Space. The Dublin group formed in 1976 from the shards of fractured bands when guitarist and singer Philip Chevron (who later joined The Pogues) met guitarist Pete Holidai. Chevron, Holidai and Trashcan vocalist Steve Rapid (birth name: Steve Averill) began rehearsing together. After the addition of bassist Mark Megaray and drummer Jimmy Crash, the collective was formed.

The Radiators started out playing covers of songs by MC5, the New York Dolls, The Velvet Underground and the Flamin’ Groovies, and the reaction was one of bemusement. At their first gigs, they were told to go away and learn how to play so they could come back one day and perform the blues.

“It was very hard for us to get gigs because nobody understood punk,” says Averill. “[Punk] wasn’t a big media thing at that point, it was just bubbling under. In a lot of cases it wasn’t even called punk, it was just called this high-energy rock music. We played this gig and the whole audience walked out on us. We felt that we were going the right direction – that if we can force an audience to walk out then we had something that was worth pursuing.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Assisted by the British tabloids’ growing fascination with punk culture, The Radiators slowly found an audience. Their gigs began to sell out, the crowds populated with punks in leather jackets, Dr Martens boots and vertiginous mohawks. This first stage of inventiveness culminated in the release of their first album TV Tube Heart in 1977. A ball of raw energy, only two of the 13 songs reach the three-minute mark. Its opening track “Television Screen” is probably the band’s most famous song and sums up the sentiment powering the genre in Ireland as they rail against an older generation that “could never understand what’s going on in my head” and demand they’re not dismissed as a blank generation. “It don’t really matter if the future looks bleak/ Cos I never see more than a tenner a week,” Averill raged.

Much of the momentum was about to come to a halt. In the summer of 1977, the grounds of University College Dublin’s Belfield campus hosted what is said to be Ireland’s first ever punk festival. The bill included The Radiators from Space, The Undertones and The Vipers (a favourite of John Peel). Tragically, 18-year-old Patrick Coultry, from Cabra in north Dublin, died after being stabbed twice during a melee in the crowd. The boy on the other end of the blade was just 17 years old. Punk music in Ireland was blacklisted.

Rowdiness – violence even – wasn’t rare at punk shows. Brian McMahon, once of Dundalk punk band The Scheme, remembers guys coming up from Dublin to a gig in his hometown and causing trouble. “I think there was pent-up energy and frustration with the youth because there wasn’t an awful lot to do,” he tells me. Stano recalls a cruel, sectarian ripple to the violence when he witnessed Belfast band The Outcasts, in Dublin for a show, taunted over their Protestant background. According to Stano, the group’s van was also the target of an arson attack.

So gigs became extremely difficult to book. “The majority of the bands who were worth listening to either split up, changed their musical style, or emigrated,” says Peter Jones (aka PA System) of punk band Paranoid Visions, who even used his 21st birthday party as an excuse to perform.

By 1983 things had started to ease up. Paranoid Visions were able to find solutions such as paying security deposits up front and keeping a better eye on the crowd. “Gradually, people started emerging from the cloak of the stabbings in 1977 to accepting the fact that the punk pound was worth having,” says Jones. “All the punk audiences were always big drinkers and always having a good time. By and large, there was nearly always some sort of a scrap, but things didn’t usually get smashed up.”

Throughout punk’s tribulations, new forms of music were bubbling in the underground. Battle-hardened veterans of the punk scene that had been drawn to its anti-establishment ethos and lack of formality felt they had outgrown the form and were eager to break new ground. Irish post-punk had no unifying sound and veered from the Pixies-esque belligerency of Cork band Nun Attax (which later filtered into Five Go Down to the Sea?), to Barry Warner’s widescreen synth-pop, to Operating Theatre’s exploratory electronica. Key to this sonic experimentation was newly affordable technologies. Suddenly, synthesizers and drum machines were attainable.

“We certainly wanted to move away from guitar and rock and hence we got the synthesizer and drum machine,” says McMahon, who after his stint with The Scheme co-founded Choice in 1980. The band initially featured McMahon on bass, Jaki McCarrick on vocals, Ciaran Vernon on synths/guitars and Noel McCabe on drums, but later became a trio when McCabe departed and was essentially replaced by a drum machine. Though the band’s recording output was small, tracks such as “Always In Danger”, with its warbling synths, icy yet serene vocals, and pop song outline, encapsulated their own strand of Irish post-punk.

When punk rock emerged in the 1970s, it was a rejection of AM radio rock, of acid-laced psychedelica, of The Mamas and The Papas’ serenity. It wanted to get rid of the hippies, the beats, the squares and the skeezers. Post-punk loved punk rock’s independent-as-f*** spirit but hated its cliché – what was supposed to be about nonconformity suddenly required an appropriate haircut. Post-punk was less anarchist and more nihilist. Never mind the Sex Pistols, here was something to groove to while you stared at your own shoelaces. Synths ate guitars. With punk, whether or not you could play an instrument felt purely incidental. In contrast, the programmed drum machines of post-punk brought a cold sense of efficiency. It subverted the subversion, but in a strange new direction.

“We tired of the drony Sex Pistols guitar, even The Ramones, quite quickly and wanted to do something different,” says McMahon, who remembers a studio engineer more used to cutting country demos being freaked out by Choice’s drum machine. “For me it was groups like Siouxsie and The Banshees and Joy Division, which had their roots in punk but were doing things with sounds. There was much more space in the songs, it wasn’t all rhythm guitar.”

In the group of new age artists seeking to test the boundaries of everything they once knew was the musician mononymously known as Stano. Once of punk band The Threat, for him, punk culture had been about being yourself and being original, and so post-punk was a natural extension of that, even if not everybody bought into it.

“When I did my first album a lot of the old punks around were asking. ‘What the f*** are you doing, Stano? Jaysus, that’s not punk.’ Well, what the hell is punk? You can’t be using a grand piano? You can’t be using a drum machine? One guy came up to me and said to me drums and piano don’t work, you have to have a bass in it. I said, ‘No I like the way it sounds, that's the way it's going to be’.”

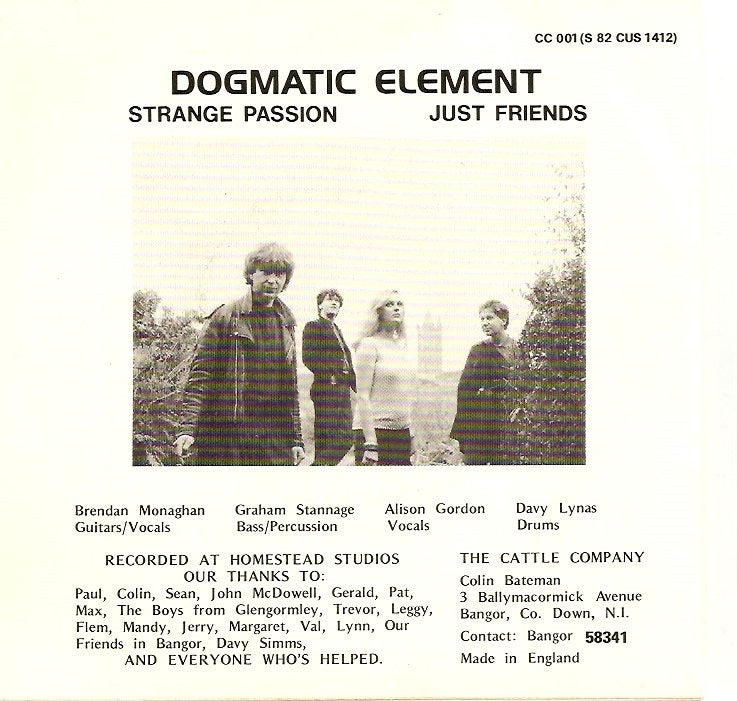

If the imagery of punk had been visceral, the post-punk style was cold and minimalist. Take Dogmatic Element, a Bangor group fronted by singer Alison Gordon. The back cover for their single “Just Friends”, a tight guitar tune, features a grayscale photo on the band taken at the entrance of Scrabo Tower, all dirty jackets, unironed trousers and unkempt hair caught in the wind. Call it their Salford Lads’ Club moment.

Averill, meanwhile, had had an affinity for electronic music that predated his time with The Radiators From Space, and left the band as a permanent member before the recording of their second album Ghost Town. His new group The SM Corporation were a gothic, haunting darkwave outfit that played with the backing of reel-to-reel tapes, over which they’d lay riffs and vocals. Averill remembers audiences being pretty baffled by the whole presentation, remembering a show when the band decided to perform their own score to the silent film Nosferatu.

“We hung a screen sheet halfway down the hall and we projected the movie onto that and played a live soundtrack watching the movie. You had all these punks with their backs turned to you watching it. At the end of the day we thought they might kill us but in fact they cheered [laughs].”

While Irish post-punk only flirted with the mainstream and struggled to cross over internationally, Dublin band Virgin Prunes found themselves performing their song “Theme for a Thought” on state broadcaster RTÉ’s The Late Late Show in 1979. It’s something to look at when you consider the show’s Catholic middle Ireland audience and reputation for generally hosting light entertainment and topical discourse. Yet here were the Virgin Prunes with their androgynous frontmen Guggi and Gavin Friday, performing an experimental art rock number. Not all the audience applauded.

For Darren McCreesh, DJ and curator of the 2012 compilation Strange Passion: Explorations in Irish Post Punk 1980-83 (Finders Keepers), the Virgin Prunes, above all other Irish bands, encapsulated the spirit of post-punk. “The performance didn’t disappoint, being utterly radical, subversive, raw and alien yet somewhat familiar, tapping into Irish Folk idioms and keening while also finding room to quote that other great Irish misfit, Oscar Wilde. It is one of the great Irish TV moments, and a moment when the disenfranchised said enough, this is our island too,” he writes in an email.

While ingenuity was happening in Ireland’s small venues, a looming presence flew over the skies of the island like a four-headed dragon. Its name was U2. The seismic effect of the band’s mammoth success on Ireland’s music scene was inevitable and it manifested in two ways: the bands that tried to cash in on the same formula, and those that rejected the formula completely.

McMahon remembers winning a battle of the bands in Trinity College with Choice in 1981. Their competition? About seven U2 clones. “Everyone had the drum and bass, guitar, male singer. And there was us with synthesisers, bass, drum machine and female singer with short pop songs. We were just so different – and better – than the rest.”

Particularly irked by U2 were Paranoid Visions. Though Jones acknowledges he thought they were a “fantastic band” when they first emerged in the late Seventies, he noticed that their success inspired a lot of groups to buy echo pedals, grow mullets and wave flags on stage. “It’s an atrocious reflection on the artists that they believe that’s the way to success – to compromise their art by copying someone else,” he says. “But it’s also a bad bad reflection on the music industry as a whole, which swooped into Ireland looking for the next U2 and everybody pandered to it. And we really got pissed off with that.”

By 1987, Paranoid Visions had started the FOAD2U2 (F*** Off and Die to U2) campaign, released a half-parody, half-diss track called “I Will Wallow”, and Jones himself even appeared on the TV show Borderline to give his thoughts on their album The Joshua Tree, which he says sparked a complaint to RTÉ from U2’s label Island Records.

While Ireland offered an ideal backdrop for punk and post-punk bands to emerge, it also threw up major barriers. Choice went the way of so many bands at the time, pulled apart by the immigrant ship as McCarrick and Vernon headed for London. Similarly, Alison Gordon of Dogmatic Element was offered a place at Canterbury University and left the band after just two singles.

The cost of studio time was an issue and there was a lack of knowledge within the industry to make post-punk thrive. McMahon believes if Choice had been helped by a svengali-like producer in the vein of Martin Hannett, who helmed Joy Division’s albums, they may have returned a better studio output. As it is, McMahon has worked to preserve Choice’s recordings, including mining songs from a copy of a copy of a dodgy cassette and posting them to Soundcloud. He mourns the missing footage of a TV performance.

Ireland hasn’t been a bastion of preserving underground music. Thankfully, compilations such as Strange Passion and Allchival’s Quare Groove Vol 1 – on which Stano’s tremendous “White Fields (In Isis)” appears – as well as Stano’s own reissues, have ensured some of the era will be remembered. Music website The Quietus, meanwhile, has Eoin Murray’s occasional column, “Anois, Os Ard”, dedicated to covering the Irish underground. These bring into focus that connection between Irish music past and present. Considered together, it asserts one thing: though the stars of punk and post-punk rejected all previous norms, their work formed what they considered to be a new strand of Irish identity.

“If you look at the likes of the Horslips and groups like that – who were so good and so radical from all the showbands – and even [Thin] Lizzy, they still had the Celtic connection. We were as Irish as anybody but we didn’t have that traditional influence in what we were doing,” says McMahon. “We weren’t consciously copying other groups that were obviously an influence, but you just felt you could see why they did things and how they were doing things. You could see where music was going, that’s what I felt. You certainly felt part of that movement or that change.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks