Finally, a Jeff Buckley film that handles his legacy with grace

This week, a docudrama about the late singer Jeff Buckley premiered at the Sundance Film Festival to a rapturous response. Hallelujah, says Laura Barton, who argues that more filmmakers should be brave enough to opt for music documentaries over starry dramatised films about celebrity musicians

These are surely the gilded days of the music biopic. In recent months, we have watched Timothée Chalamet turn into a puckish Bob Dylan in A Complete Unknown, Kingsley Ben-Adir’s interpretation of Bob Marley in One Love, and Marisa Abela’s take on the role of Amy Winehouse for Back to Black.

It is also not long since we saw fictionalised versions of the lives of Whitney Houston, Elvis Presley, Elton John, and Freddie Mercury. We have even witnessed Robbie Williams bafflingly play himself as a chimpanzee in Better Man. Still to come on the horizon: dramatised takes on the lives of Boy George, Billy Joel, Janis Joplin, Kiss, Linda Ronstadt, Nat King Cole, Frank Sinatra, Michael Jackson, the Grateful Dead, the Bee Gees and The Beatles.

I am, I confess, not a huge fan of musical biopics. It has always seemed to me that something is lost in the enactment: the individual becomes untethered from the music itself; the essence of an artist and their music evaporates. Instead we are left with something proficient, impressive, but somehow largely unmoving.

In Amy Berg’s forthcoming documentary about Jeff Buckley, we find something moving happily against the biopic trend. Buckley was a fairly minor musical figure in his lifetime. It was only after his death, at the age of just 30, that his album Grace, and in particular his version of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah”, came to be celebrated.

It’s Never Over, Jeff Buckley was an emotionally intense project for Berg, taking 15 years to make. The director veers from the trend for fictionalised narrative, drawing instead on archival recordings, the singer’s notebooks and childhood photographs, and a series of expansive and sensitive interviews she conducted with his previous girlfriends – the artist Rebecca Mason, Elizabeth Fraser of the Scottish band Cocteau Twins, and Joan Wasser, who records under the name Joan As Police Woman. When it premiered at Sundance last weekend, it was met with a standing ovation.

One can see quite readily why, in the hands of another director, Buckley’s life might be considered richly suited to the standard Hollywood biopic treatment. The son of singer-songwriter Tim Buckley, Jeff met his father only once before Buckley Sr died of a heroin overdose in 1975. Instead he was raised by his mother, a classically trained pianist and cellist, and his stepfather – the family living somewhat itinerantly (and without much financial security) around California.

For several years, Buckley worked as a session musician and focused on expanding his repertoire, discovering Sufi devotional music in addition to artists such as Van Morrison, Bill Evans and Nina Simone. In 1991, he performed at a tribute to his late father at a church in Brooklyn, including in his set the song “I Never Asked to Be Your Mountain”. Tim Buckley wrote it for his former wife and young son, having left them when Jeff was just six months old.

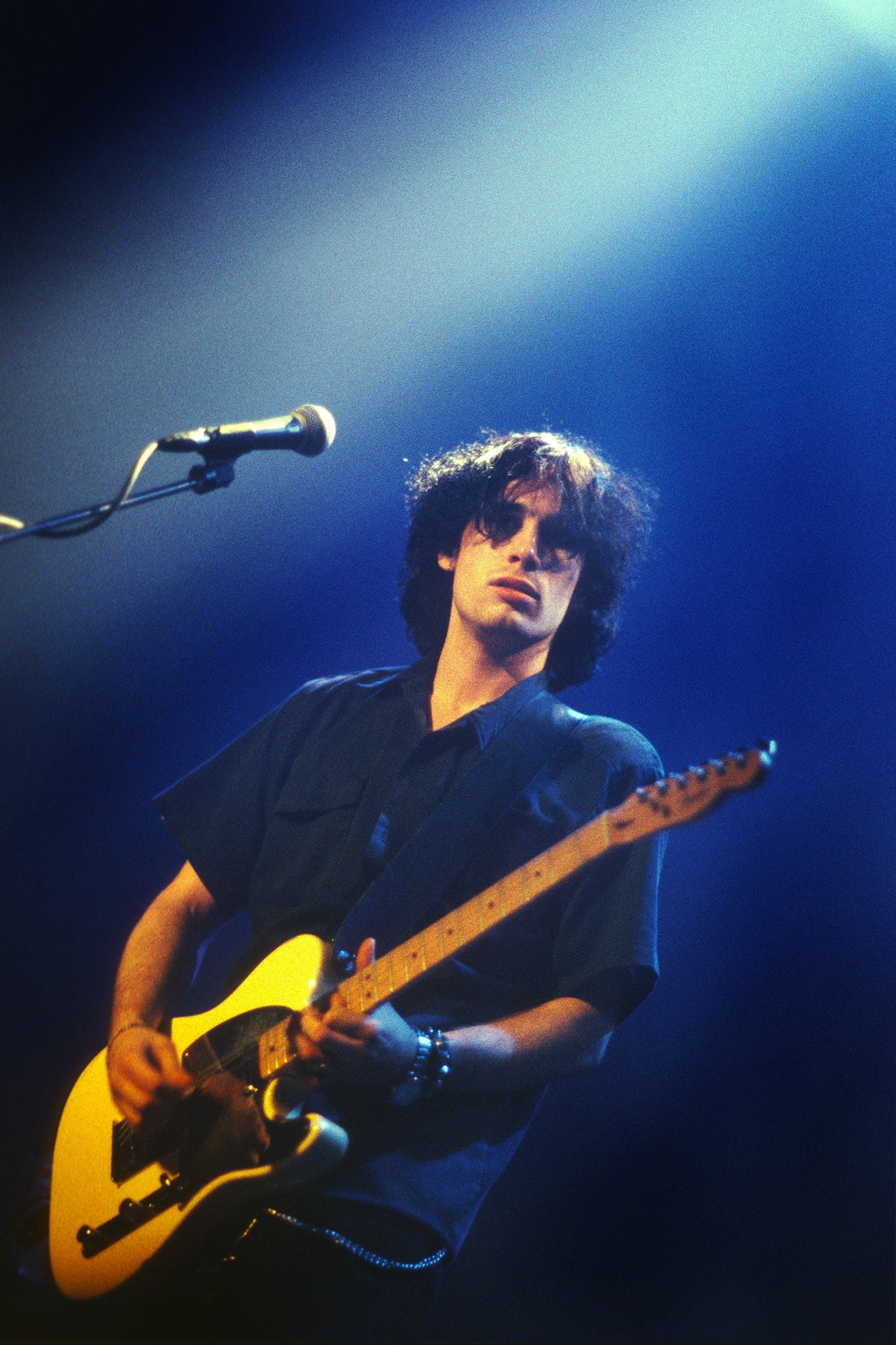

By the early Nineties, Jeff was a regular name on the bills of the bars and clubs of Lower Manhattan, steadily growing a reputation that in 1992 would earn him a $1m deal with Columbia Records. It should be noted that he was also an exceedingly handsome young man – dark-eyed, high-cheekboned and pale-skinned; he had a look that was both classically attractive and particularly in vogue in those Grunge-framed years. The cover of his debut album Grace positioned him as some brooding troubadour in a white T-shirt, eyes downcast, hand gripping a vintage microphone. He was that rare thing: hipster heartthrob and musical virtuoso.

The great promise of Jeff Buckley was always part of his tragedy. In 1997, while swimming in a tributary of the Mississippi, he was swept under the water by the wake of a passing tugboat and drowned. Grace had been released three years earlier, and at the time of his death he was in Memphis at work on its successor. While his debut did not see great success in his lifetime, receiving little radio play and reaching only 149 in the US Billboard Top 200, the thought of what he might have made next has always been utterly compelling.

Buckley’s music was dramatic and romantic and soulful and furious; it moved from sparse arrangement to heavily orchestrated, jazz to frenetic blues rock, and, alongside his cover of Cohen, took in interpretations of Nina Simone’s “Lilac Wine” and Benjamin Britten’s “Corpus Christi Carol”. Bob Dylan named Buckley one of the Nineties’ finest songwriters, and artists from David Bowie to Jimmy Page have spoken of their love for Grace.

After Buckley’s death, sales of his debut climbed, and today the album holds platinum certification in many markets. A high-profile placing of his version of “Hallelujah” on The West Wing, and performances of the song on television talent shows – heavily influenced by his version – have propelled the singer to mainstream attention.

While Buckley singer has long been coveted, romanticised and undoubtedly a little fetishised, it has always felt fitting that the executors of his estate have taken a somewhat dignified approach to his legacy. There have been only a few posthumous releases. The box sets and best-ofs have been far from abundant, the film and television syncs carefully selected.

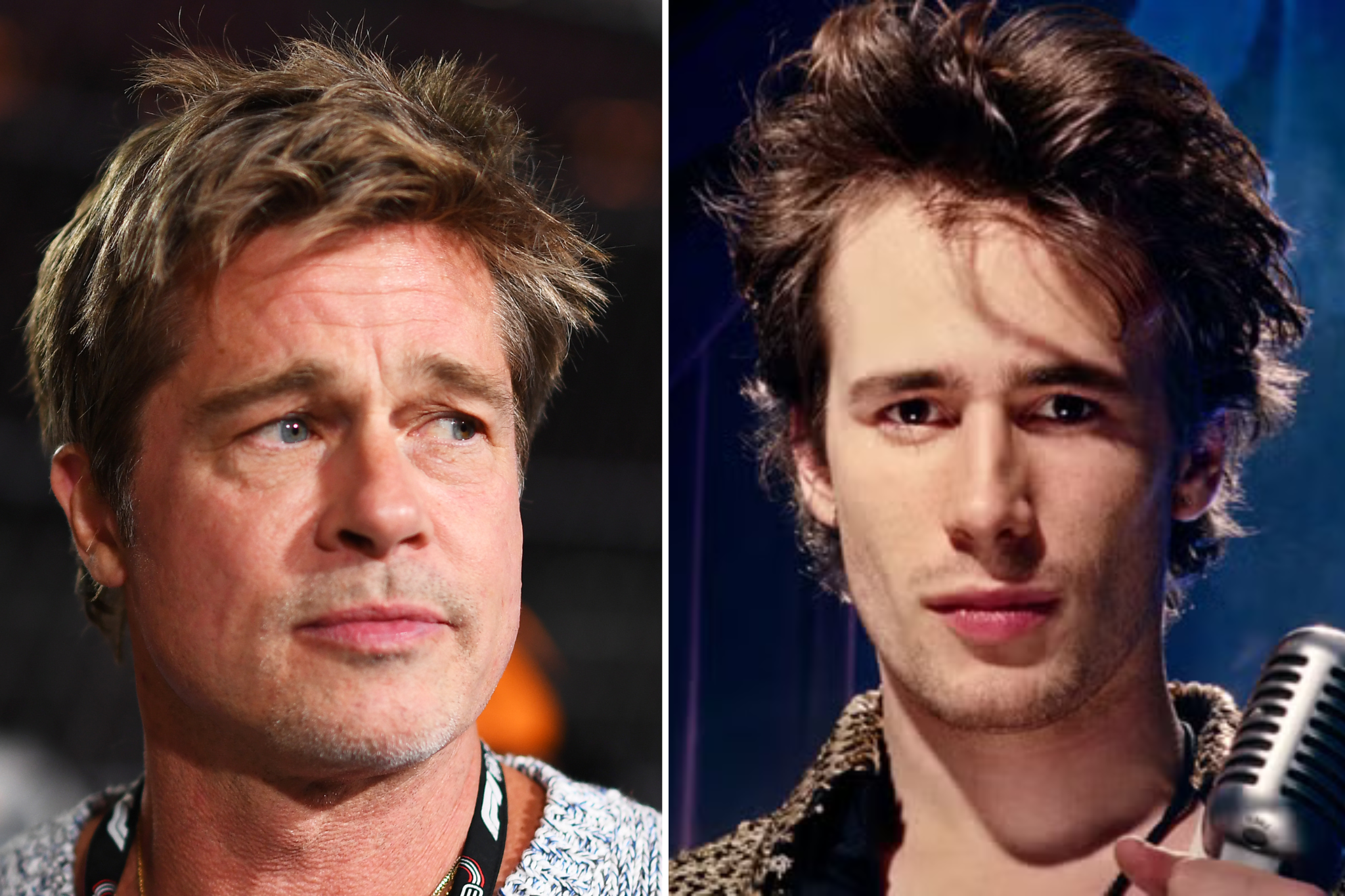

Moreover, the singer’s family have always resisted the call of Hollywood. In 2000, Brad Pitt attempted to persuade Buckley’s mother, Mary Guibert, that he should play her son in a biopic, by inviting her to his wedding to Jennifer Aniston. Although Guibert initially agreed, she was never fully convinced.

One day, she turned to Pitt and set out her reservations: “We’re going to dye your hair, put brown contact lenses on those baby blues, and you’re going to open your mouth and Jeff’s voice is going to come out?” There is something pleasing about this: it suggests that there might be a limit to such cinematic burrowing; that there are some musical heroes whose gifts might remain unblurred by impersonation.

There was certainly an argument for Berg to narrativise Buckley’s life for her film. The recent rise of the biopic is in part due to the reputation of these films for being cheap to make, easy to market, and often high-grossing. They provide a narrative pleasure similar to that of the faltering superhero franchises – a hero rising against the odds, only (in some cases) to fall back down. Their success also arrives at a point when rock’n’roll, now 75 years old, has come to be regarded as a serious art form. But Berg stood firm: “Once I started listening to his voicemail messages and his DAP player and demos and reading his journals, I just couldn’t imagine it being anything but a documentary.”

In 2008, Buckley’s version of “Hallelujah” became his first US No 1. Its revival was thanks to the song’s appearance on American Idol, where it was performed by a contestant on the show’s seventh season. That year in the UK, it was kept from the top spot by The X Factor winner Alexandra Burke’s cover of the same song. Listen to the two versions again now, and you will hear how preposterous that was – Buckley inhabiting Cohen’s lyrics and breaking them open anew; Burke processing through the song in a series of impressive but passionless melismatic turns.

It is much like the sensation I have when I think about musical biopics – struck by how remarkable the transformation is, how deadening the result, and how strangely rare it is to discover a film in this genre that inhabits the music.

Buckley’s version of “Hallelujah” opens with the singer drawing breath: a kind of audible shorthand for intimacy and proximity, for a mortal being celebrating something divine. Berg’s film performs a similar trick, reminding us that her subject was not a movie role or a superhero, but a person who, through music, touched something greater than himself.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks