Why Morrissey’s downfall echoes the messy demise of The Smiths

As pariah status beckons for Morrissey, Ed Power looks back on the downfall of one of the most important bands of the Eighties

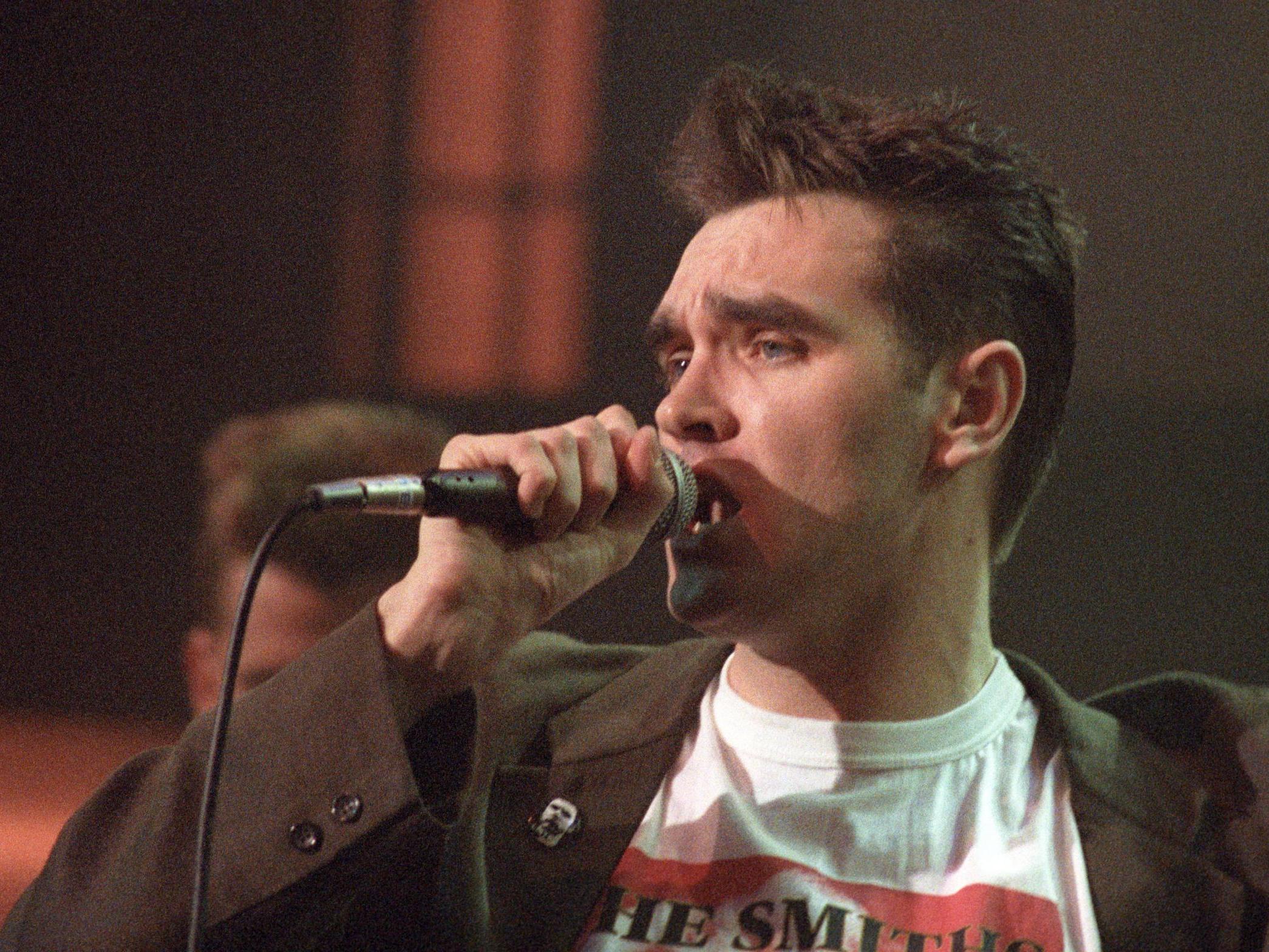

The Smiths were supposed to be the band who saved all the drama for their music. Yet their great, 12-month unravelling was a true Grand Guignol epic, sloshing with vitriol, tears, tragic misunderstandings and Moz throwing a hissy fit on a revolving stage in Italy.

All of that and a great record, too. As Morrissey prepares to release his 13th solo album, I Am Not A Dog On A Chain, it feels instructive to reflect on the demise of The Smiths. The group has, after all, cast a shadow over everything he has done in the past 33 years.

The obvious reason for looking back is that for the Morrissey of today, there is a sense of looming finality. Pariah status beckons for the former generational icon. His 2019 endorsement of the far right New Britain party, and his claim – the latest in a series of outrageous outbursts – that “everyone ultimately prefers their own race”, have pushed him past respectability for many former fans. The campaign to “cancel” Morrissey gathers pace. Might I Am Not A Dog On A Chain ring a closing bell on his life as mass-market entertainer?

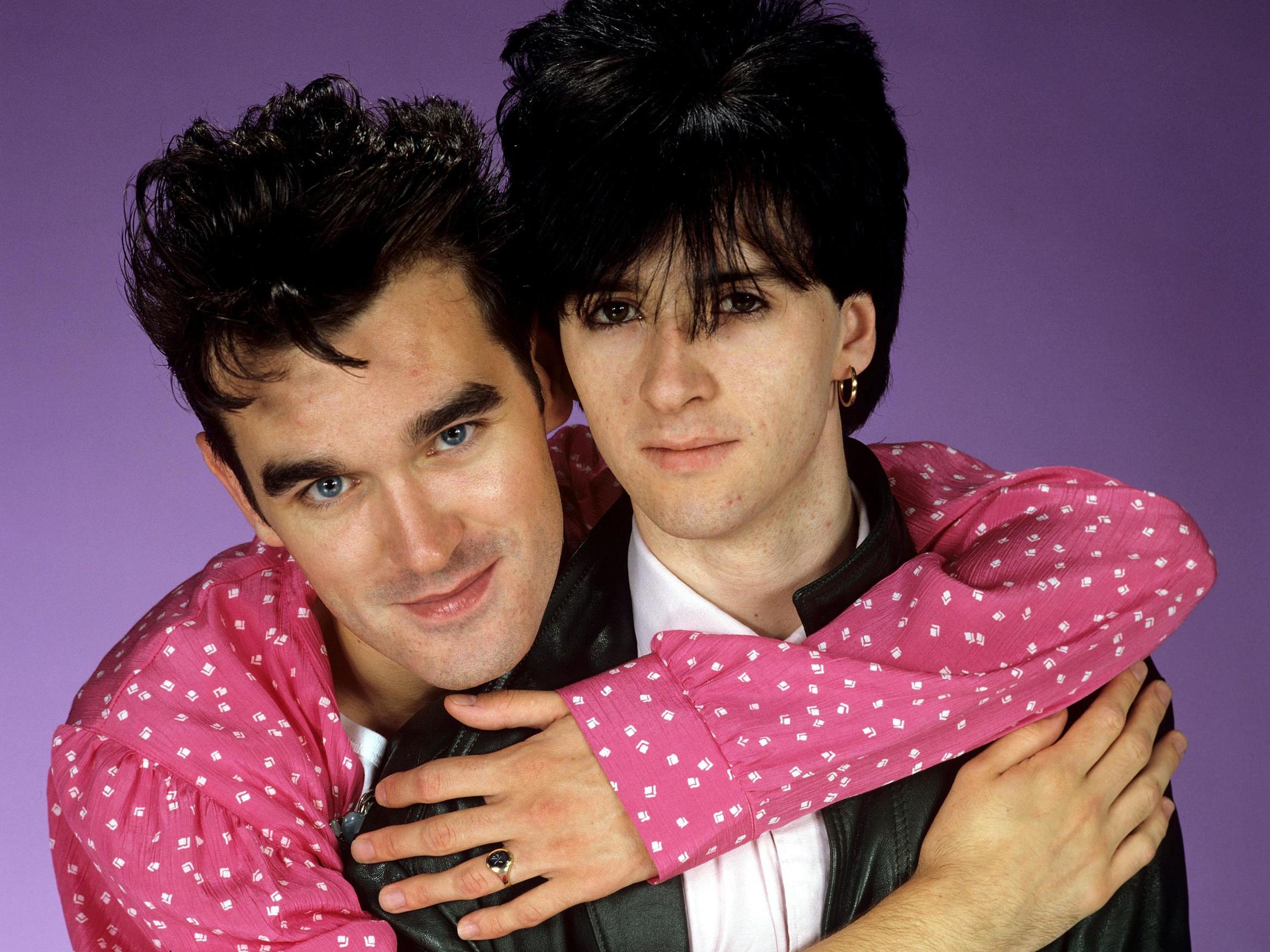

It is hard to say. The Smiths had no idea the end was nigh when they assembled at Wool Hall studios near Bath in March 1987. As had been the case since Morrissey and Johnny Marr first played together five years previously, in an attic rehearsal space in the Manchester suburb of Bowdon, it was a tightly knit group that had gathered at the facility. There was singer Morrissey, guitarist Marr, bassist Andy Rourke, drummer Mike Joyce, Marr’s wife Angie, producer Stephen Street, and the group’s manager Ken Friedman.

Friedman, who also worked with UB40, was new in the job and quickly becoming a cause of unhappiness. Morrissey liked to boast that The Smiths were unmanageable. They had recently parted from Matthew Sztumpf, who had helped negotiate a lucrative major label deal with EMI after the quartet concluded they were better off leaving their indie powerhouse Rough Trade.

Their desire to quit Rough Trade had been a source of tension with its founder Geoff Travis. He had gone so far as to take out an injunction, essentially preventing them from bringing their 1986 album The Queen is Dead to another record company.

Morrissey’s brag about The Smiths and unmanageability was an extension of his belief that the band could take care of business themselves. He was the guiding light in the group’s artwork and, via his gladioli and James Dean fandom, largely shaped their public persona.

The less glamorous heavy lifting, meanwhile, fell to Marr. In addition to playing guitar and writing all the music, he negotiated contracts, organised tours and even got on the phone to sort out buses and hotels. Marr had pushed for Friedman because he was fed up with being the one literally keeping the show on the road.

Still, that March, the outlook was rosy. Positively ebullient in fact. The evening they pitched up at Wool Hall, the band – minus the puritanical Morrissey – had partied until daylight. Marr, whose cocaine and crisps diet had seen his weight at one point shrink to dangerous levels, had moved on to a fresh obsession: brandy.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Everyone else was more than willing to join him in this new love affair. Parties at Wool House became a nightly event. With Morrissey tucked up in bed with his favourite Sylvia Plath anthology, the musicians would cover their favourite Spinal Tap songs into the wee hours. How bracing to picture the great sensitive tunesmiths of their generation howling “the bigger the cushion, the sweeter the pushin’” at 3am in a converted barn in Somerset.

It was a happy time. And despite their very different lifestyles, Morrissey and Marr were at that point working well together – like hand in glove, as it were. Outsiders generally assumed that Morrissey wore the figurative corduroys in the songwriting partnership. And it is true that Marr deferred to him, though the situation would grow more complex as the band fell apart.

Yet in many ways, Morrissey was the more stable component of the relationship. He struck many beyond the group’s immediate circle as immensely odd – a sense that would accentuate as The Smiths hurtled towards their break-up. Still, he was happy in his bubble and could actually be more approachable than the mercurial Marr. Geoff Travis, for instance, got on far better with Morrissey than with Marr, whom he is said to have found distant.

Marr, in his way, was just as needy as Morrissey. And he was sensitive about being exploited, feeling he had for years carried The Smiths in an organisational capacity. What he needed, more than anything, was to feel supported and appreciated. In his 2016 biography, Set the Boy Free, he described the early weeks in Wool Hall as among the happiest of his time in The Smiths.

“I was in my element,” he wrote. “I didn’t need to know what was going on in the outside world or see anyone other than the band and Angie … I loved the new songs.”

They didn’t know it yet, but The Smiths had already played their final concert. It was in February 1987, at northwest Italy’s San Remo Festival, on a revolving stage. Spandau Ballet and Paul Young were on the bill, too, and happy to sing in the round.

However, when the stage malfunctioned, Morrissey declined to continue with what he felt was a charade. It had been Friedman who convinced him to go on and belt out a selection of the band’s hits as they slowly pivoted through 360 degrees.

At Wool Hall, though, Morrissey’s relationship with the manager started to fray. The closer the newcomer grew to Marr, the more Morrissey seemed to take a dislike to him. Smith and Joyce were quick to side with the frontman – as Marr immediately noticed.

“New allegiances were formed between band members and I was having to defend the merits of our new manager,” he wrote in his book. “I didn’t understand why there was a problem. The band’s business was finally being looked after … But the rest of the band made a sudden U-turn and it was three against one. I could feel the positivity I had for the future slip away.”

In the end, he was pressured into firing Friedman. He didn’t want to, and resented being pushed into a corner. The tension also seemed to get to producer Street. He felt stung after an incident in which he had helped Marr write a string section. Street suggested, as matter-of-factly as he could, that he was open to receiving a songwriting credit for his contribution. Marr gawped at the producer as if he’d asked the guitarist to pledge him his first-born child.

Then there were the fraught interactions with Rough Trade. After the disagreements over The Queen Is Dead – the label had genuinely feared The Smiths would cut and run to a major with the master tapes – the relationship was shaky. Morrissey had taken a snarky shot at Travis on The Queen is Dead’s “Frankly, Mr Shankly”, singing “I want to leave, you will not miss me/ I want to go down in musical history.”

“I saw the lyric as part of Morrissey’s desire to be somewhere else, so it’s not completely silly,” Travis would say. “It was The Smiths’ prerogative to leave Rough Trade and Morrissey can only write about his own experiences.”

The Smiths had signed a five-album deal with Travis. As a goodwill gesture, though, Rough Trade would allow them to leave after Strangeways, Here We Come, their fourth official LP (there had been compilations and B-side collections). A more cynical band would have tossed out 50 minutes of filler and gone on their way.

Marr, however, wanted to use the opportunity to expand The Smiths’ sound. In particular, he was eager to escape the jangly, student-disco pigeonhole into which they had been wedged.

Morrissey, too, was yearning to move in a different direction – just not the one favoured by Marr. This would come to a head that summer, when the singer pushed Marr to cover Cilla Black on a B-side.

“Towards the end of The Smiths, I realised that the records I was listening to with my friends were more exciting than the records I was listening to with the group,” Marr said in Johnny Rogan’s seminal Smiths history Morrissey and Marr: The Severed Alliance. “Sometimes it came down to Sly Stone versus Herman’s Hermits. And I knew which side I was on.”

Tensions were starting to bubble up. In April, with their profile rising in the US, where they were signed to Warner Music’s Sire Records, it became necessary to film a video for the (non-album) single “Sheila Take A Bow”.

Twenty-three year old hotshot American video director Tamra Davis was flown in to oversee the shoot (Davis would go on to marry Beastie Boy Mike D). As arranged, the band turned up at Brixton Academy. But Morrissey had chosen to absent himself.

Frustrated, Marr went with Davis and Friedman (who wouldn’t be sacked until the second week in May) to the singer’s Knightsbridge flat. He refused to come out.

“I remember very distinctly that I had no idea if Morrissey was standing behind that door laughing at the three of us pleading with him, or crying,” Davis told Tony Fletcher in A Light That Never Goes Out: The Enduring Saga of The Smiths. “Johnny was like, ‘That’s it. The band is over’... And he walks away.”

Davis had already made an effort to win over Morrissey. She had visited and they chatted at length in his bedroom. He declined to get out of bed and struck her as the oddest person in the world. The young director couldn’t work out whether he was genuinely eccentric or simply putting it on to unnerve her.

Dragged into a confrontation between Morrissey and Sire, and having fired Friedman, Marr was close to packing it in. The mood within the group had turned even darker during their final recording sessions in May, where they were to work on B-sides for the “Girlfriend In A Coma” single. Morrissey wanted to cover Cilla Black’s “Work Is A Four Letter Word”. Marr recoiled. “I hate ‘Work is a Four Letter Word’,” he said. “I didn’t form a group to perform Cilla Black songs.”

And then there were Morrissey’s pointed lyrics in the other B-side, “I Keep Mine Hidden”. “The lies are easy for you,” he crooned. “Because you let yours flail into public view.” Marr felt he know at whom the words were directed.

He visited Morrissey’s flat and they had a heart-to-heart. A few days later, the band convened at Geales, an upmarket fish and chip restaurant in Notting Hill. There, according to Fletcher’s biography, Marr revealed that he’d received offers to play on a new record by Talking Heads and to collaborate with Bryan Ferry, and would be saying yes. With that, he was off. Morrissey, Rourke and Joyce concluded that he had just quit.

“I don’t remember if I said I was going to leave the band or not … But I said that we needed a break and that we needed to rethink what we were doing,” Marr recalled. “They could have sat there and listened to me being re-enthusiastic about a reinvention of my life and their lives. Or they could have heard me say those words as, ‘This is the end, I want out, I’m not coming back.’ Which is what they did.”

The death knell was sounded by an NME cover on 1 August declaring that The Smiths were about to split. The story was largely cobbled together. But Morrissey was sure Marr had leaked it. Marr, in Los Angeles for a holiday and to explore future musical opportunities, likewise thought Moz was whispering in the ears of journalists.

For the guitarist, it was one slight too far. A week later, convinced Morrissey would be the first to bail, Marr called NME to tell them the story was correct: he was out. The band briefly tried to soldier on. They even considered hiring Ivor Perry as a replacement. But on 28 September, Rough Trade confirmed it was all over.

Strangeways, Here We Come was released the same day, to a predictably bittersweet reception. It is, in many ways, The Smiths’ most diverse work. Morrissey acknowledges his Irish family heritage on opening track “A Rush and a Push and the Land Is Ours”, which takes its title from a quote by Oscar Wilde’s mother, Lady Jane Francesca Wilde, published in 19th century Irish nationalist journal The Nation.

The singer even plays piano – well, it’s more a crazed banging, really – on the loose-limbed and playful “Death of a Disco Dancer”, the only time he’s played an instrument on a Smiths record. And the record contains one of The Smiths’ catchiest hits, the aforementioned “Girlfriend In A Coma”.

Strangeways, Here We Come was clasped tightly by fans as a farewell memento from a band that had remade pop and changed lives. How different a reception Morrissey is likely to receive with his new album. It’s a perfectly respectable affair that, alas, cannot escape the fatal gravity of his divisive persona.

As for any hopes of a Smiths reunion… even in the unlikely event of Morrissey’s former bandmates getting his politics, it’s clear the singer has little interest in returning to old glories. “Yes, time can heal,” he wrote in his rambling 2013 autobiography. “But it can also disfigure.”

I Am Not A Dog On A Chain is released on Friday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks