Doc and roll: Why we’re living in the golden age of music documentaries

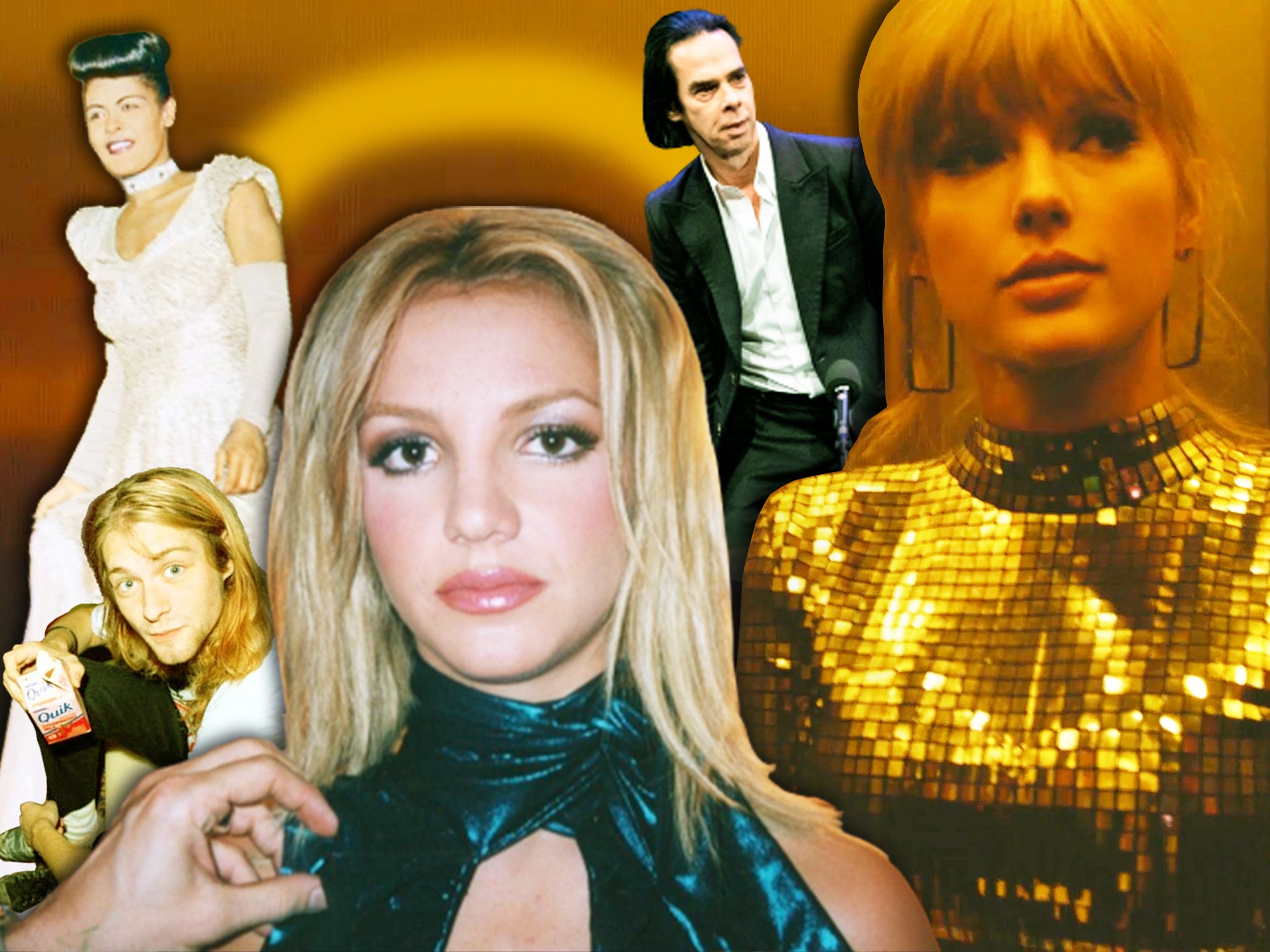

No longer empty hagiographies, docs like ‘Framing Britney’ and ‘Reclaiming Amy’ can change the way we think about pop culture. Elizabeth Aubrey charts the medium’s evolution and talks to the directors behind films following Taylor Swift, Bros and Nirvana

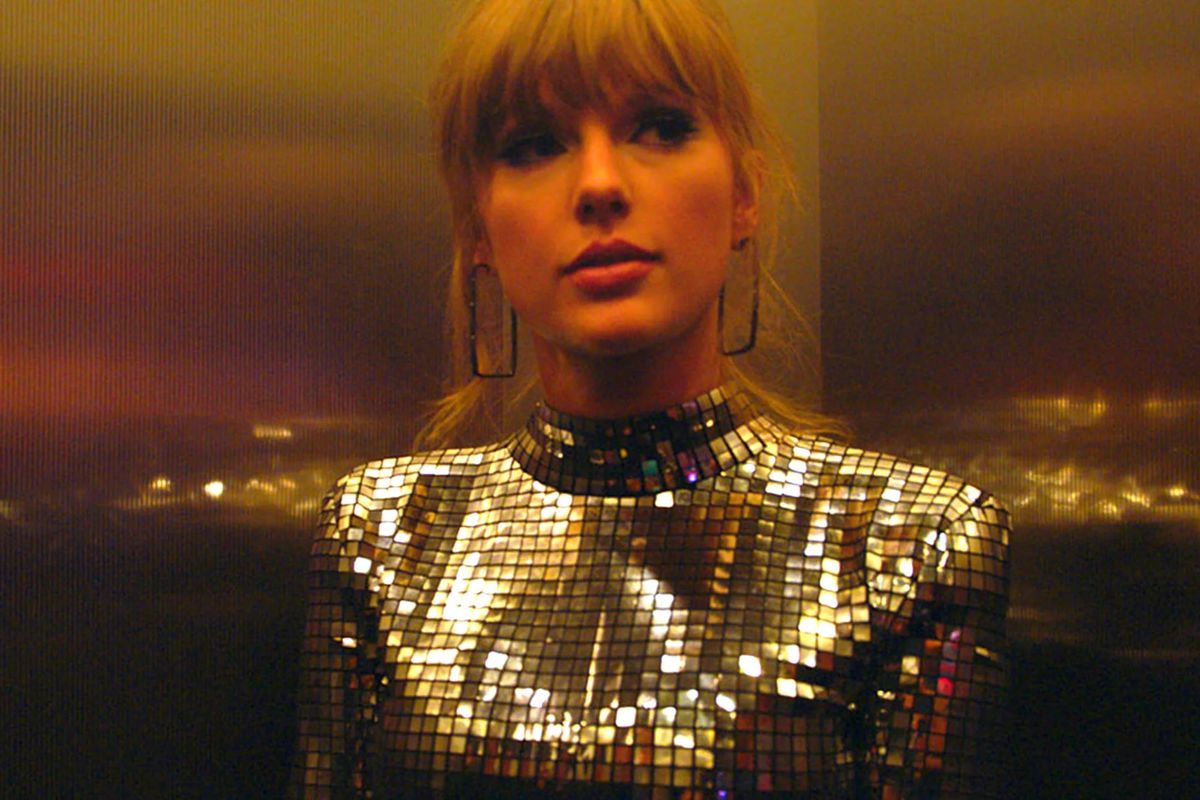

It has to be about much more than music,” Lana Wilson, director of Taylor Swift’s Miss Americana, says on what makes a successful documentary about a musician. “As I filmed and events unfolded, I realised people watching this film are not just seeing their favourite pop star; they’re not just seeing one of the best songwriters of all time in action. They’re seeing a model of how you can be a woman in this world and not be silenced.”

Wilson’s film was a revealing portrait of one of the biggest A-listers in the world in a climate where access to pop stars is often limited or increasingly guarded. It sees Swift painfully exploring her battle with media scrutiny, something that led to an eating disorder; the turmoil that followed a sexual assault; and how she dealt with news of her mother’s cancer diagnosis. It seemed to go beyond a mere hagiography – awkward topics were not glossed over but tackled candidly; narratives appeared free from the restriction of record labels who often see the form as a mere promotional tool.

“I didn’t have any contact with record labels while making Miss Americana,” Wilson says, saying she was determined to tell Swift’s “true story”. She continues: “Access is always a challenge, for any documentary. Here, it was about building trust with Taylor. That took time, patience, and more time. Taylor made it really clear to me that she wanted an outsider to make a film looking at her, that had a real perspective that came from the director. She wanted this to be the story that I saw in her life and wanted to tell.”

Miss Americana arrived last winter, alongside several other music documentaries that proved hugely popular and a lot more genuine than what had come previously, like Frank Marshall’s new take on the Bee Gees in How Can You Mend A Broken Heart and James Erskine’s revelatory documentary Billie, which used a journalists’ old interview tapes to tell Billie Holiday’s story in a new and surprising light.

The rise of the music documentary continued this summer, too, with the release of The Sparks Brothers, Edgar Wright’s critically acclaimed love letter to Sparks, Questlove’s far-reaching Summer of Soul, about an influential Harlem music festival erased from history and BBC Two’s Reclaiming Amy, Marina Parker’s re-exploration of the death of Amy Winehouse, which recently became the most requested music documentary on BBC iPlayer ever. With 1.57 million streams, it overtook previous record-holder, BBC Four’s Bros: After the Screaming Stops, which was a cult phenomenon and a meme-tastic viral hit.

Lorna Clarke, controller at BBC Pop, who commissioned both documentaries, says the most successful films tend to tell a bigger story. “Often a story can be much more impactful by being about much more than music,” she explains, like the Bros documentary, whose themes of sibling rivalry, fame and family reconciliation – as well as their can’t-look-away personalities – gripped the nation. “It made the industry think again about how we make music documentaries,” Clarke says of the film. “It also proved that music stories don’t have to be about the biggest stars. It may just be the strongest story featuring music and human interest – in this case, the story of two brothers.”

After the Screaming Stops’ director, Joe Pearlman, says he wasn’t aware of Bros’s music before the film: initially, he was just asked to make a film about a comeback gig with the brothers. “I went to meet the boys in LA and immediately knew there was a lot more to this story than what was being presented,” he explains. “I knew the relationship was so complicated, so much pain and hurt was [evident] between them – but also a genuine desire to be closer.” Pearlman spent months living with the pair to get to the truth about their relationship. “Their life became my life – we spent literally months living in their pockets,” he says. “I have to give everything of myself over to their story to deliver anything that feels genuine. It’s got to affect me, otherwise it’s not going to affect the viewer.”

Pearlman said he had no interest in making a hagiography either. “I think films like this and [other documentaries] of late have been able to peel back the skin on the onion and give us something a little bit less record label-controlled and present it in a more genuine and honest way. The result is something much more fulfilling.” He also says he doesn’t think he could have made this film had he been a fan of Bros. “It meant I had the ability to see past fandom and past the music and see who the real people were. If you’re a fan, you could get clouded, or end up making a film for the fans. If I was making a film about Bob Dylan, then I might struggle.”

As a filmmaker, Wilson isn’t in the business of making a film for fans either. “The thing I always asked myself was, ‘Is this something that anyone can connect to, even if they don’t like Taylor Swift’s music?’” she says. “I think one challenge with the music documentary as a form is that it can proceed a bit like an illustrated Wikipedia entry. When I watch a film like that, I’m often resentful – like the film is assuming I know and love the main character from the beginning, just because they’re famous. It’s taking my interest for granted.” She wanted Swift’s story to resonate widely: “I hope the film is both a coming-of-age story that millions of young people can relate to and an examination of how we treat powerful women in our culture, media and world.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Wilson says social media has also significantly changed the landscape of film documentaries. “We all have public and private personas now,” she says. “We’re all struggling with the difference between what people think your life is and what it actually is. There’s the public version of the story and then there’s the real internal truth that no one knows and no one sees. One thing I talked about with [Taylor] early on, maybe even at our first meeting, was that I saw not simply a rarefied celebrity existence, I saw a young woman who had grown up in the public eye and who faced an extreme version of the challenges many women and girls face.”

Clarke, too, is looking for stories that go well beyond a glossy, controlled social media portrait of a musician that may be being driven by the artist’s themselves or the label – but it’s not always easy. “We’re in constant dialogue with artists’ management about how we can tell their talent’s stories,” she explains. “A big change we’ve seen in recent years is that the artist is more in control as they’re becoming executive producers of their own content. It’s become usual for an artist to arrive at one of our pop radio stations with a film crew in town, creating footage for their social media feed or forthcoming documentary. The challenge is how I can help them shape some of that content. The challenge is trying to be as close to artists’ stories while remaining an independent editorial story.”

Award-winning filmmaker Jeanie Finlay, who worked on music films like Orion: The Man Who Would Be King and The Great Hip Hop Hoax, says she turned down many offers from record labels to make films about artists where there’s often no story or it’s a clear “puff piece” – where there’s little independence when it comes to telling the artist’s true tale. “The fact that they can breathe is not enough,” Finlay laughs, recalling conversations with labels asking her to make sanitised films about artists. “I had a meeting with a record label once and I pitched three films about really iconic female bands and artists that they held the [music] rights to. I wanted to tell the stories of women and feature more women on screen. They were all influential; one was cult. They listened to me for ages about the need to tell the stories of women and at the end they just said: ‘How about...’ and named a male, middle-aged man who is very nice, but there was no story. They just wanted to shift units.”

Filmmakers like Finlay, who are brave with the stories they’re telling, is one reason why the format is resulting in a critical boom, says Neil Fox, whose upcoming book for the BFI Music Films: Documentaries, Concert Films and Other Cinematic Representations of Popular Music explores the history of the music doc and its growing popularity. “It’s a great time for the music documentary right now,” says Fox, the best of which he says “engage with issues of class, gender, privilege, labour, race and art in ways that are not didactic but inquisitive, funny, moving and enlightening.”

The best music documentaries find a story and are independent in the way they tell that story, free from label or artistic control

He says they also “seek to represent their subject in a cinematic way where the style and tone of the film is spiritually akin to the music and the musicians at the centre of their story. They are fun, make beautiful use of archive [material] and contain great interviews. They find a story and are independent in the way they tell that story, free from label or artistic control.”

Fox adds, though, that the format is undergoing a commercial golden era, driven “by that icky word ‘content’”. The lines between an independently told story and a hagiography are blurring more than ever before. “The need for content for streamers has driven the boom in part, in particular Netflix, who are buying up and are producing a ton of music documentaries,” he says. “This has been met on the other side with the music documentary being seen by star performers as a key part of the content they offer. It’s seen lucrative pairings for performers. Beyoncé’s Homecoming, for example, is both a brilliant concert film but also a very carefully managed showcasing of her vision, her determination, her talent and her labour.”

This idea of what stars want and don’t want you to see was underlined this week when Alanis Morissette slammed Jagged, a new HBO documentary made about her life. Morissette had agreed to be interviewed for the film but later released a statement to express her upset at how the film had turned out, saying, “this is not the story I agreed to tell”. Likewise, Amy Winehouse’s father Mitch recently reacted angrily to news that another documentary was being made about his late daughter, saying it was “100 per cent not allowed”, his upset from Asif Kapadia’s Oscar-winning Amy still evident. The family were heavily criticised after the film’s release, and they recently directly condemned Kapadia’s film in Reclaiming Amy, saying the story presented was not one they recognised about their daughter.

Wilson says no matter who she makes a documentary about, she shows the subject the final cut to avoid situations like this. “We did show Taylor a cut before it was finished,” she explains. “I do this with all of my subjects – whether they’re an abortion provider, a Zen priest, a Dutch neuroscientist, or Taylor Swift! It gives us a chance to have a conversation, and for the subject to tell me if anything feels inaccurate to them. It’s important to me that the subject feel respected and valued in this process, because I know how much trust they are putting in me, to tell a story about their life, and who they are as a human being.”

Fox says films authored or heavily influenced by artists or their families – or where the lines blur between independent documentary and hagiography – need treating like a whole new “sub-genre” in the field. “For many artists and labels, the music doc is something they can control more than previously. Music documentaries have always been promotional to a degree by design, but now they’re seen as a key to a performer’s persona. It’s no longer obscure punk bands or legacy white rockers who are the focus. Everyone is getting in on it.”

When commissioning documentaries for the BBC, Clarke says she is looking for “a strong journalistic angle with a valid voice, telling what might be a familiar story in an unfamiliar way”. Though Clarke didn’t commission it, perhaps the best recent example of a fresh format like that is James Erskine’s Billie, which told Billie Holiday’s story in a compellingly original way and with zero filter. Erskine spent years hunting down 50-year-old tapes of interviews with the stars of jazz and blues about the singer, carried out by writer Linda Lipnack Kuehl in the Seventies, which had never been played in public before. Their only existence was only known via transcripts that a handful of journalists had read decades earlier. The result was a doc that told Holiday’s story, but Kuehl’s alongside it.

“We managed to track down the mythical tapes with a private collector. They were in a couple of musty old shoe boxes. They hadn’t been played since they’d been recorded,” Erskine laughs. “We did a deal, flew to New York and took them to this special preservation studio in Chelsea. It was the first time they’d been played in like 50 years and immediately we were transported to the world of Charles Mingus backstage somewhere decades ago. We had the whispers of the past and a gateway into Billie’s world.”

Erskine had to carefully piece together an untold story about Holiday from over 200 hours’ worth of tapes. The process took years. “We just had to go through it and piece the material together slowly,” Erskine says. “I sat with a whiteboard and a marker and worked out almost like a musical how we’d put in Billie’s music alongside the content of the tapes so that we always keep her story front and centre. The tapes showed us how people who were with Billie viewed her and how Billie presented herself.” Erskine and his team had the tapes colourised too, giving viewers the first ever look of Holiday in technicolour. “Billie was incredibly vibrant. It brought her to life in a new way.”

Erskine says he was supported by Holiday’s family and estate in his quest to tell the truth of her difficult life, something he says made for a better documentary. “I would call out for record companies or the estates to be brave with this, because the better films are the ones that tell the good and the bad and then actually, the art becomes bolder against that complexity,” he says. That complexity included the race and gender issues that Holiday came up against time and time again in her career. “It was important to represent Billie as somebody that was trying to possess her own voice in a society that stopped her,” Erskine continues. “I wanted to show a story of someone who was strong and who won so many battles.”

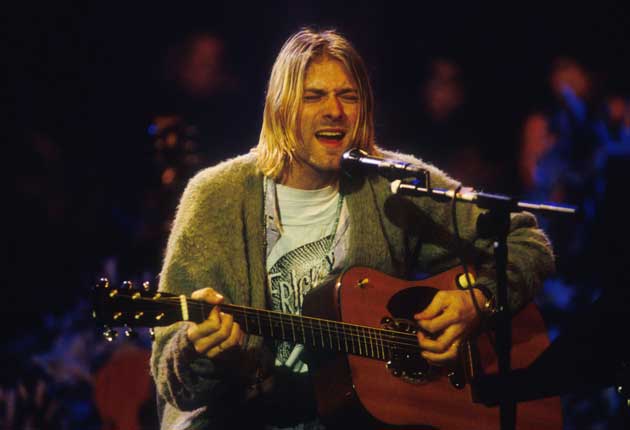

Another documentary that tells a familiar story in an unfamiliar way – and goes to extraordinary lengths to do so – is a new work celebrating 30 years of Nirvana’s game-changing 1991 album Nevermind: When Nirvana Came to Britain. Producer Stuart Ramsay says he and his team scoured the UK searching for never-before-heard eyewitness stories about Nirvana’s time in the UK during the early Nineties. What he found paints a new picture of Kurt Cobain, Dave Grohl and Kris Novoselic told by everyone from fans to venue owners, hotel workers to van drivers, pub landlords to dancers.

“Nirvana were massive at this point and Kurt and Dave just turned up at this tiny pub in Edinburgh to perform,” Ramsay recalls of one of the eyewitness accounts he gathered. “Their tour manager’s brother was in a local band, and they somehow persuaded Kurt and Dave to do an acoustic set for charity. When word got around, thousands turned up, but the pair were late. Most people left, apart from a handful of people. They eventually arrived and those who stayed got to see Kurt and Dave perform one of the most intimate sets of their careers.”

Ramsay says he hopes viewers will be surprised by what they uncovered. “I think there’s a lot of myth-making, a lot of misconceptions about what Nirvana were like because of ultimately what happened to Kurt,” Ramsay explains. “But if you look at some of the fan footage as well as footage the band themselves found for us, you see them messing about, you see how innocent they are and how much they just love being in a band. This was a time when they didn’t have the pressure of being seen as spokespeople for a generation – they were just loving being in a band and making music.”

Kurt wasn’t this doom-laden figure – he had a sense of humour, was funny, making jokes

He continues: “Kurt wasn’t this doom-laden figure – he had a sense of humour, was funny, making jokes. We also saw just how ahead of his time he was too. He was writing songs and talking in interviews about feminism, speaking out against toxic masculinity and showing support for gay rights. Rock stars weren’t doing that in the Nineties. He was years ahead of the game.”

Ramsay says because the bar has been raised so high now in music documentaries, filmmakers are starting to experiment with form and structure more than ever before – something he thinks will lead to even more ambitious filmmaking in the genre in years to come. “I think a more cinematic approach is being sought after, like with [my doc] we didn’t have a voiceover that was really the done thing a few years ago.” Instead, Nirvana’s story is largely told through eyewitness accounts, emboldened by rare footage and visceral archive photography. “There are more non-linear structures too, plus in the UK with the demise of things like Top of the Pops and reality TV shows like The X Factor, there is space for these types of music films to make it onto top programming slots now, which is exciting.”

The social power of music documentaries has been in the spotlight too this year, like the explosive New York Times documentary Framing Britney Spears, which told the story of Spears’s alleged controlling conservatorship against a backdrop of her treatment as a woman in a patriarchal industry in the early Noughties.

The film spurred the #FreeBritneymovement further – the results of which are now being seen as the current trial unfolds. One fan on social media said the film was “the moment the world took this seriously”. Another said: “The pressure the film brought changed everything.” Likewise, Channel 4’s new documentary series, Spice Girls: How Girl Power Changed Britain, raises historical questions about the misogynistic treatment of women in the Nineties music industry. In turn, this is now promoting debate about young women artists now who are still being subjected to similar objectifications.

Fox says the power of the documentary in raising awareness of such issues and initiating change shouldn’t be underestimated. “Music documentaries can use celebrities and artists to bring to wider public knowledge and consideration a variety of cultural and societal issues,” he says. “Recent examples include the treatment of women in the music industry (and wider society in general) in films like Kate Nash: Underestimate The Girl, conservatorships in Framing Britney Spears, trans identity in Keyboard Fantasies: The Beverly Glenn-Copeland Story and grief and trauma in One More Time With Feeling [Nick Cave]. These films and others like them are accessible ways to engage audiences on timely and long-standing issues and experiences and help move us towards changing and better understanding them.”

But even so, music documentaries could still be under threat. Despite their popularity and influence, Finlay says that budgets on smaller, independent music films are suffering extensive cuts across the arts, meaning many are still struggling to get made. That will result, she continues, in an erasing of the films that have made the genre so exciting and critically acclaimed in recent years – meaning they’re in danger of being replaced with bigger films where directors have less editorial independence.

The places to make small, intimate films are more depleted than ever

“Documentary in the UK has always relied on broadcast money and with the depletion of BBC Four and Channel 4’s loss of their feature documentary slot, the places to make small, intimate films are more depleted than ever,” she explains. “It looks like there is more opportunity, but actually, it’s more challenging because you’re having to make stuff that proves a market demand. It’s as tough as it ever was to get these films made. Many want the commercially viable doc-busters but with these... there’s [often] much less creative freedom.”

And with the documentary-as-star-vehicle showing no signs of slowing, the next time you see a big pop name pop up on Netflix promising a tell-all insight into their lives, perhaps we should be wary. The popularity of the format shouldn’t overshadow the importance of a strong narrative, says Erskine. “I think there are endless legs for the format yet, but it has to drive itself through the story. There’s a danger of the attitude of ‘documentaries are cheaper to make than films’, but the starting point always needs to be the story rather than: ‘This is a really great artist with an audience and therefore money.’ That is what will diminish the format and will be its greatest challenge in the future.”

‘When Nirvana Came to Britain’ is on BBC Two on Saturday 18 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks