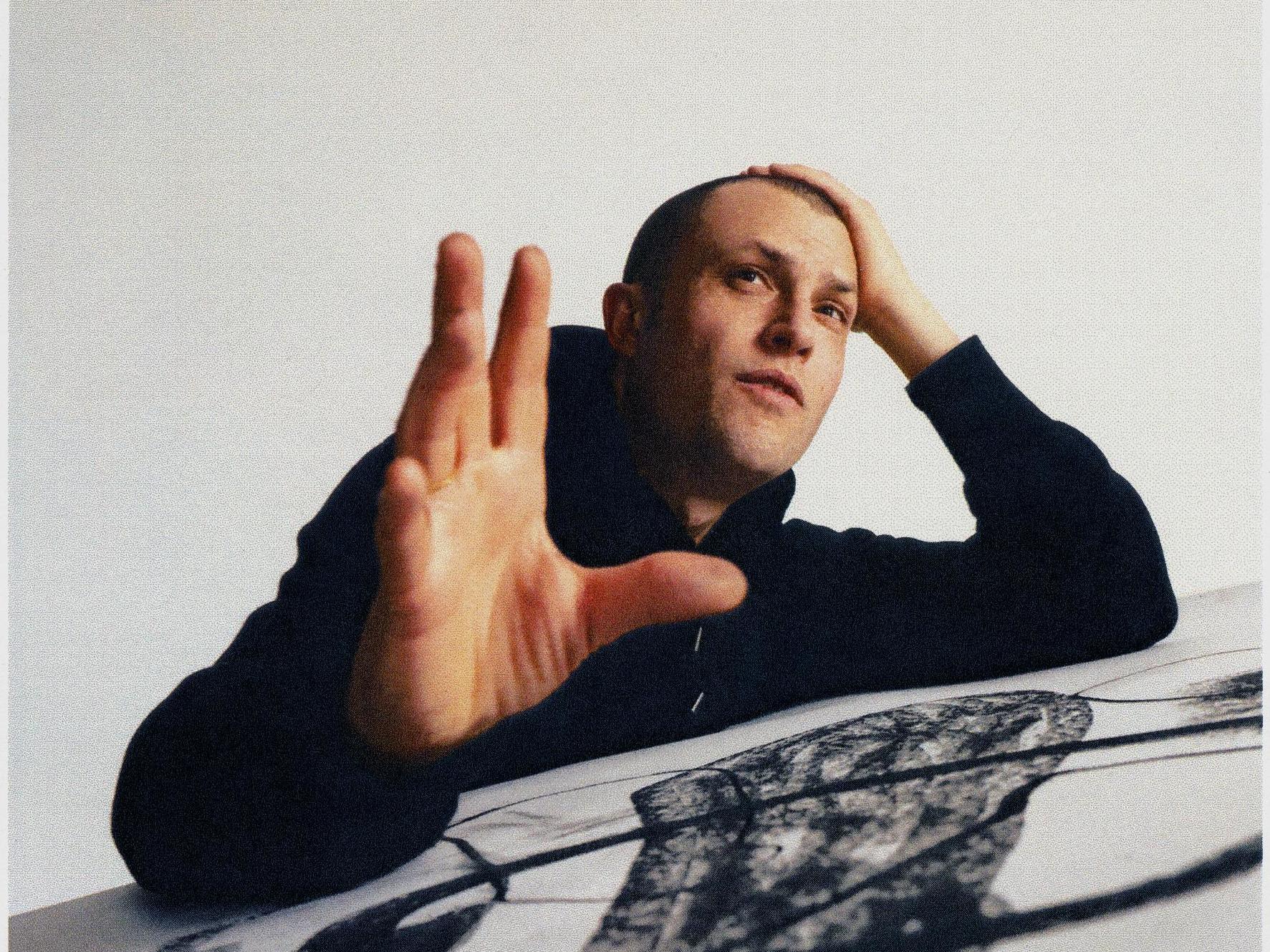

Orlando Weeks: ‘We had a difficult time making the last Maccabees album, but the reason for the split is our thing’

The former lead singer of the indie rockers is releasing his first solo album, all about fatherhood. He talks to Mark Beaumont about avoiding coronavirus doom-mongers, the potential for political change, and becoming the new Talk Talk

For a man who stood on the threshold of big-league glory, peeked inside and walked away, Orlando Weeks is remarkably zen. His old band The Maccabees split in 2017 at the height of their success, headlining Latitude Festival, selling out multiple nights at Alexandra Palace and hitting number one with their fourth album Marks to Prove It, but, Weeks says, there were no complaints of “but we’re next in line!” Having developed from frenetic outliers on the Noughties guitar scene into purveyors of expansive alt-rock elegance, The Maccabees were on the brink of stepping up to the major festival headline slots, taking their seat at rock’s top table. And then, like ghosts in smoke, they were gone.

“It felt like we’d made such good strides with [third album] Given to the Wild,” Weeks ponders via Skype, “and that maybe we had not moved on as far again with Marks to Prove It, and we’d been doing it for a very, very, very long time. Even if we had thought ‘we’re next in line’, I don’t think that would’ve been a reason to carry on.”

Was it his idea to split? “It was everyone knowing that that was what was going to happen. We’d had a difficult time making that final record and we’d reached the end of the line,” he says. “It just ran out of steam a bit.” What was difficult about it, I press. “Just all the things that are usually difficult about making work with four other people, and everyone minding.” Was there any animosity? “It was just a difficult thing to do. When you’ve been in each other’s company and worked on everything together for so long, it’s complicated. It was a difficult time, but it was what we needed to do.”

For the first time in our hour-long virtual chat, Weeks starts to sound a little unsettled. I get the impression he hasn’t processed the split completely. “Maybe not,” he admits. “I also think it’s kind of our thing. In some ways we were lucky it never ‘took off’. There was enough momentum for us to have enough freedom to be experimental and try and move ourselves along, and at the same time not being bound by one song or one record that defined us.”

Serenity descends once more. Locked down in Suffolk and just over the 18-month hump of first-time fatherhood, Weeks is a lesson in level-headed pandemic survival. He’s avoiding the “doom-monger” end of his friends list and “seeking out the more optimistic people on my phone. You have to celebrate the things that are joy, don’t spend too much time on anything that isn’t.” He’s staying creative, writing and drawing and planning alternative online ways to exhibit the artwork he’s put together around his first solo album, A Quickening. “I was hoping there’d be an opportunity to have an exhibition of all the work that’s gone into it and maybe do some shows in that space and have a residency, but that’s not gonna happen.”

Artistically minded – he studied illustration at Brighton University – and never one known for rampant hedonism or ego, Weeks has chosen a post-Maccabees path of picturesque placidity. He moved with his partner to Berlin for a year, not to rave for England for entire weekends like most who make the move, but to “play piano, do drawings, mooch along the canals, drink beer in the afternoon” and create The Gritterman, a wintry children’s book inspired by his grandad Bill, who repaired traction engines and heavy farming machinery in Devon and Cornwall. The book spawned an accompanying album, which Weeks recreated live with Paul Whitehouse playing the titular unsung hero in 2018. Then, via six months in Lisbon (“If you’re in a touring band you stay in a place for a day or two days and think ‘it’d be nice to be here a bit longer’, and there was no reason why not to,” he explains), he wound his way back to the UK, there to construct a debut solo album on the theme of impending fatherhood.

“Once we knew we were expecting I found it very difficult not to write about it,” he says. “Most conversation when you’re expecting your first child seemed to come back round to that. It’s what you think about a lot, it’s what you read about, what you’re trying to educate yourself on. Because of what you search for it’s algorithmically what you’re presented with [online] – it’s quite hard not to have it be front and centre in my mind. It was so present.”

More attuned to Foals’ duskier moments than The Maccabees’ more fervent tunes, it’s a gorgeous record of gentle yet profound moods, homely and reflective yet capturing the awe and anxiety of encroaching parenthood in its amorphous horn swells, organic textures and glutinous throbs and heartbeats that could’ve been sampled from within the womb. “I was writing at a piano at the other end of the flat trying not to wake up the baby,” Weeks says. “I hope it doesn’t sound as tired as I felt a lot of the time.” There are reflections on prenatal tests and ultrasounds, and shopping trips for clothes for someone as yet unborn, but, I wonder, are there any parts that he intended to reflect the first warm flush of nappy overflow down your forearm?

“I struggled to find the poetry in the nappy overflow,” Weeks grins. “Almost all of the record is pre-baby arriving. It’s the waiting game. ‘There is someone coming’ – having that as the final lyric on the record, and the first song on the record, ‘Milk Breath’, is the only song that’s about a world where he’s here with us, it feels like it’s the wrong way round.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Has fatherhood made him fear for the future? “Yeah, there is that. There’s a lot of doubt and with doubt comes a space that anxiety can creep into, and that anxiousness is not fun. I was worried that that might be my experience afterwards, that that would get worse. Actually, the combination of the amount of love that you feel helps get rid of some of that, and you suddenly become aware that there’s so much that can go wrong that if you start trying to think about it, you’re blinded by the numbers.”

A singer who walked away from popular chart success to make oblique, boundary-pushing freeform mood music on his own terms… hang on, is Orlando Weeks the new Talk Talk? “I definitely remember feeling, the more I spent time listening to later Talk Talk and the Mark Hollis record, there is a sort of naked effort in the way that he sings that makes me feel better about the way that I sing. It sounds like he finds it quite hard sometimes, and I feel like I sound like I find it quite hard. I also think there’s lots of ways of spinning off Talk Talk in the same way there’s a lot of ways of spinning off Robert Wyatt, and where you spin off to, I seem to have a nice time there too.”

The artful tones and nuances of A Quickening won’t appease those who marked Weeks down as a graduate of the school of modern rock privilege. The privately educated son of a public affairs lobbyist, Weeks admits to having felt insecure and out of place at school but began making music more because “I enjoyed the problem-solving of it” than to exorcise his demons. Will the new album play into the hands of those who argue that, according to the ancient punk tablets, great music comes from struggle, and that he hasn’t had to battle enough to really “mean it”?

“To each their own,” Weeks says. “If I got too bogged down in that I couldn’t do anything. I’m trying to make things that I think are sincere and heartfelt and doing something at the edge of my ability as much as I can. I completely respect someone’s opinion: if they discount anything that I make because of that, that’s OK.”

A fairer take might be that Weeks is emblematic of guitar music’s gradual, decade-long shift from energetic melody to evocative textures and atmospheres, although he’s excited by the new punk breed. “IDLES are great and I particularly loved Brutalism as a record, I think it’s a very beautiful piece of grown-up rage. And I remember thinking how incredible Fat White Family were live when I saw them at EartH (Evolutionary Arts Hackney), it felt like you were looking in on footage of something else, it was so good.”

In Weeks’s world, then, a tentative tranquillity reigns. Has it given him any insights into the post-pandemic world? “There’s two answers,” he decides. “There’s the optimist in you that says we needed a shake-up and we’re all going to have realised how much we miss each other and how we should all treat each other better. Then there’s the pessimist who thinks about the economic catastrophe across the world and as soon as you start going down that road you try to remember what the optimistic points were. It’s too big for my tiny mind.”

Politically, is coronavirus pushing us past post-truth and into the post-lie era, where the falsehoods and spin become impossible to swallow in the face of a catastrophic death toll and impending economic collapse?

“My worry is what seems to have happened is that if you pile lie upon lie upon lie upon lie upon lie,” Weeks says, “it makes it very difficult for people to call you out on any one thing. So what you have is this splurge gun effect that makes it impossible to pick the correct hole in that scattergun of lies… It seems to me that in America Trump completely understands his base and plays on that, making it very hard within their electoral system to imagine how someone can beat him. And here, who knows? It does make the potential for a Labour government far greater. It moves the goalposts enough to maybe see whether we should have a different government, it opens that as a possibility.”

That’s all to come, but right now, in celebrating new life rather than fretting over mankind’s many predicaments, A Quickening is the perfect record for soothing away these anxious hours. Finally, a delivery you can hold close.

‘A Quickening’ is released on 12 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks