Murderous lyrics, bare torsos, and disappointment: the story behind The Smiths brilliant debut

Forty years ago, The Smiths released their now-iconic self-titled debut album. Mark Beaumont speaks to drummer Mike Joyce about the trouble bubbling behind the scenes, the controversies it stirred, and how it came to inspire and define an indie rock explosion

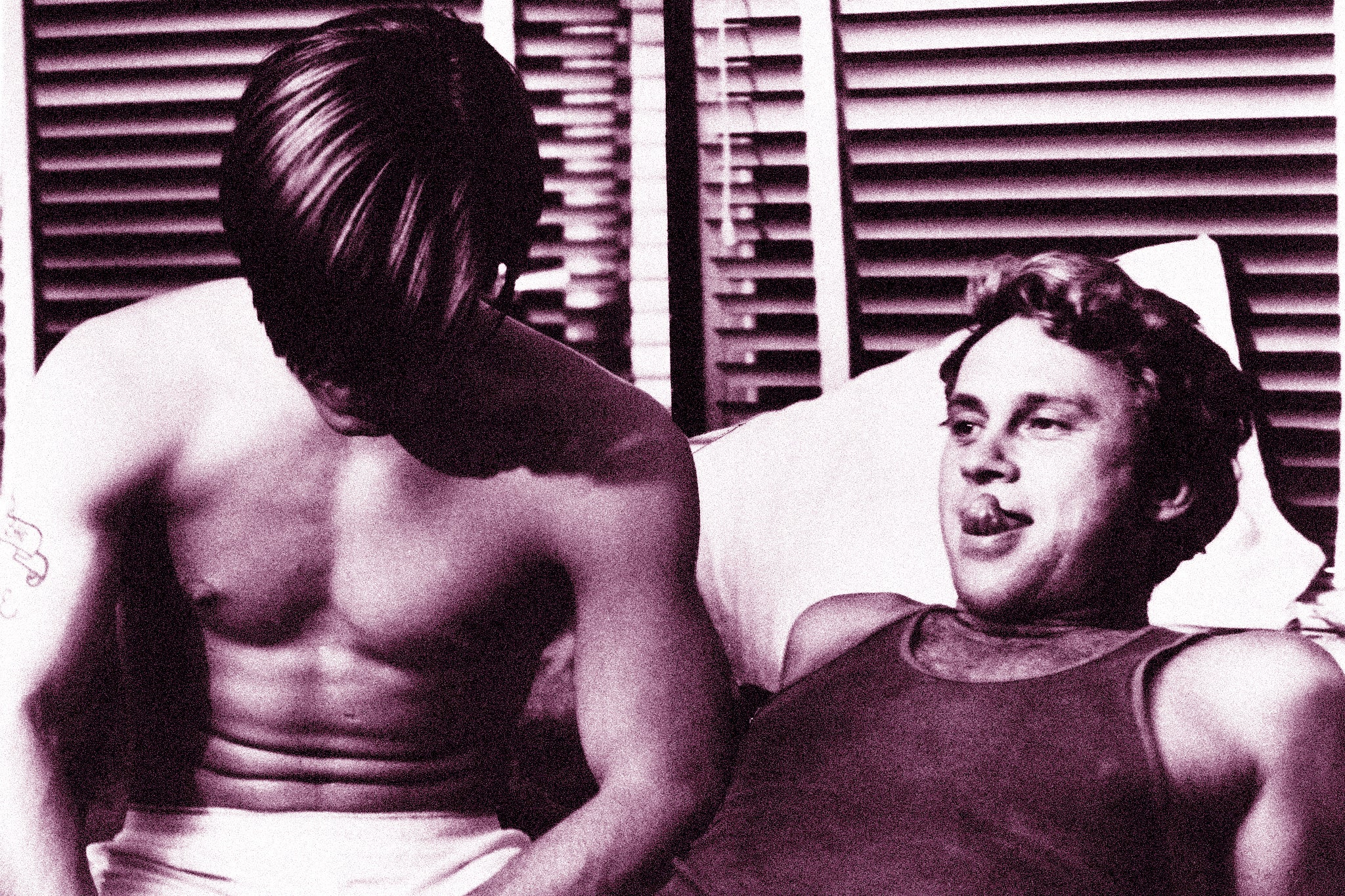

When Morrissey first showed his bandmate Mike Joyce the image he’d chosen to grace the front cover of their highly anticipated 1984 debut album, The Smiths drummer found it too close to the knuckle. It was a tender shot of actor and gay idol Joe Dallesandro alongside a lusty co-star, taken from Andy Warhol’s 1968 film Flesh.

“I think Dallesandro and the other guy are both New York hustlers and I think he might have been w***ing him off or something along those lines,” Joyce, now 60, recalls over Zoom. “I was pretty freaked out. I thought ‘I can’t wait for my mum and dad to see that – and the local priest.’”

Morrissey had been remiss in not informing Joyce that the image would be cropped for the album cover to include just Dallesandro’s now-iconic bare torso, cutting out the image’s less Woolworths-friendly elements. Regardless these were the sort of cultural shocks Joyce had signed up for when he joined Manchester’s most transgressive and artistically minded band of the age. “I didn’t say, ‘What? You can’t do that, oh my god!’” he laughs. “It was cool.”

Despite its instantly recognisable album art, The Smiths’ self-titled debut opened more ears than eyes when it was released 40 years ago next week. Fans of the keytar-and-flappy-trouser age were fascinated by its unusually whimsical and poetic opening with “Reel Around the Fountain”; its bursts of punk falsetto and ferocious ennui on “Miserable Lie”, “Hand in Glove” and “What Difference Does It Make?”; its intricate guitar tapestries and minutely crafted images of kitchen sink drama (that rented room in Whalley Range, that sore-lipped kiss beneath the iron bridge). And, between its maudlin musings on broken friendships, lost love and loneliness, lurked themes darker than Lou Reed’s Berlin dared plumb: prostitution, sexual disgust, the Moors murders.

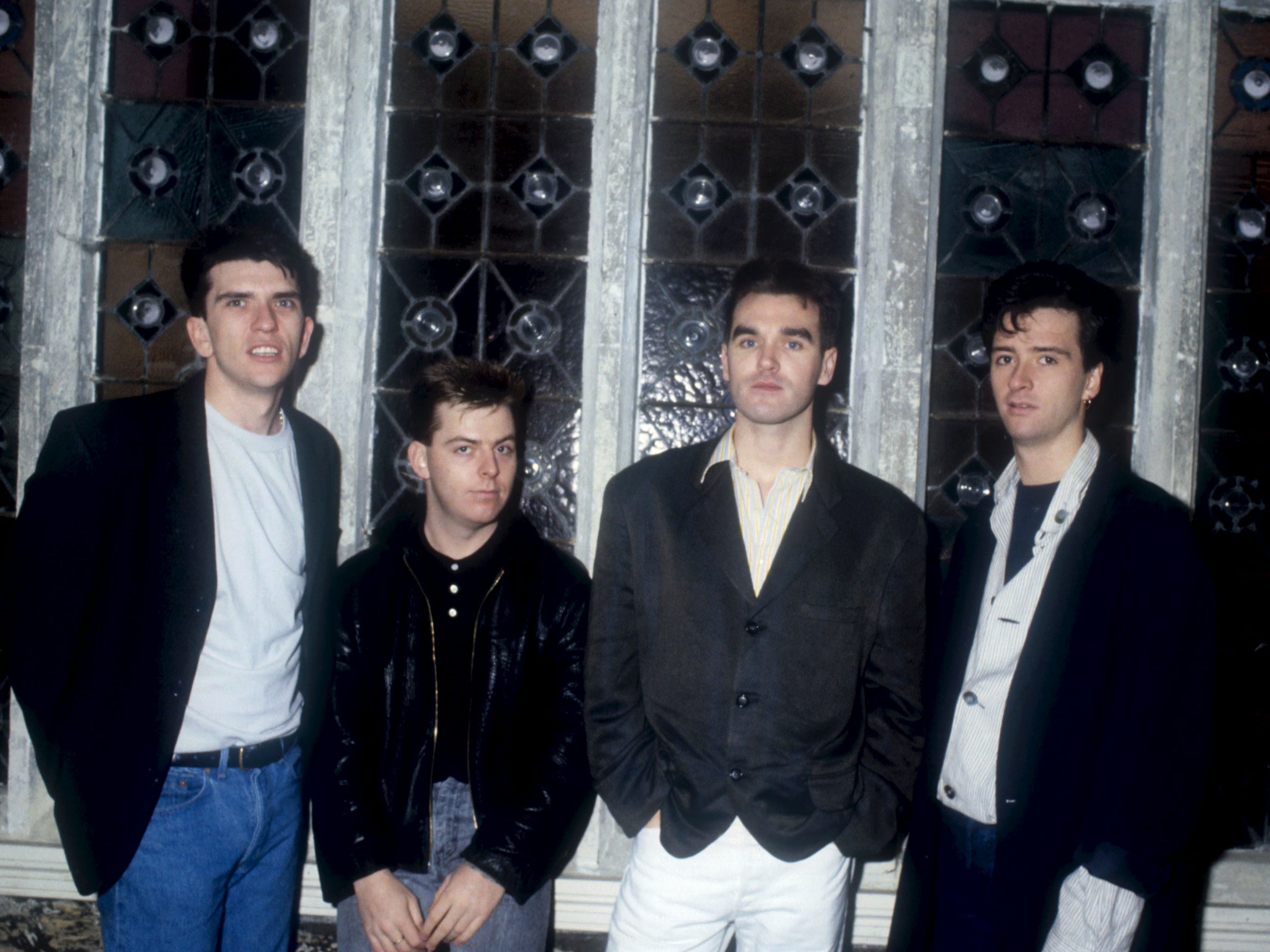

The Smiths emerged from a rich seam of early Eighties alternative acts finding melody in the murk, from the post-punk abrasions of Wire, Joy Division, Siouxsie and the Banshees and The Cure through to the austere alt-pop of Echo & the Bunnymen and REM broadcasting their hazy college rock from the ghost dimension. But something in the union of Johnny Marr’s weightless guitar lines, Andy Rourke’s elaborate bass, Joyce’s often breathless beats, and the relatability of Morrissey’s arch and literate lyricism fostered a sound and aesthetic that would inspire and define an indie rock explosion.

For the rest of the decade, and some way beyond, angst-wracked young men and women (although mostly men) draped their growing pains and romantic failings over jangling guitars in a nationwide confessional ardour. To declare oneself “indie” back then was to pronounce a well-read discernment, melancholy demeanour, and depth of emotion, which Level 42 and T’Pau fans could hardly comprehend – and, frankly, were probably happier without. It was a movement encapsulated by the NME’s legendary C86 cassette compilation, which in turn evolved into shoegaze, indie pop and the early howlings of Britpop. Not a bad legacy for a record that The Smiths themselves were disappointed with.

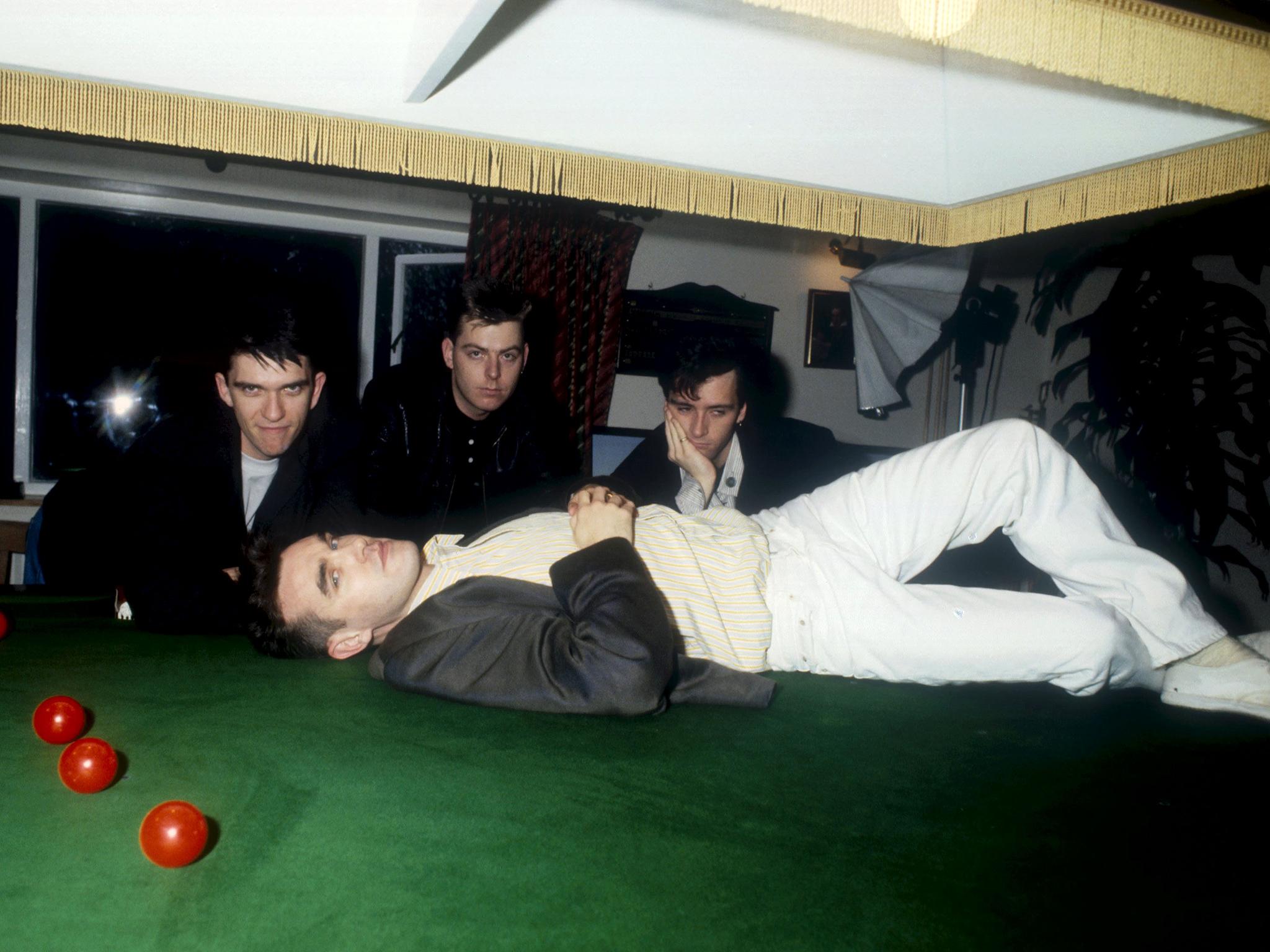

As with many debut rock albums, the songs for The Smiths had been honed to a laser-point live by the time they came to record them in the summer of 1983. “We wanted to try and capture the essence of that live set,” says Joyce. “Each track had been given its own life because we played them live. We were coming off the back of quite a lot of gigs and the tracks were gig hot.”

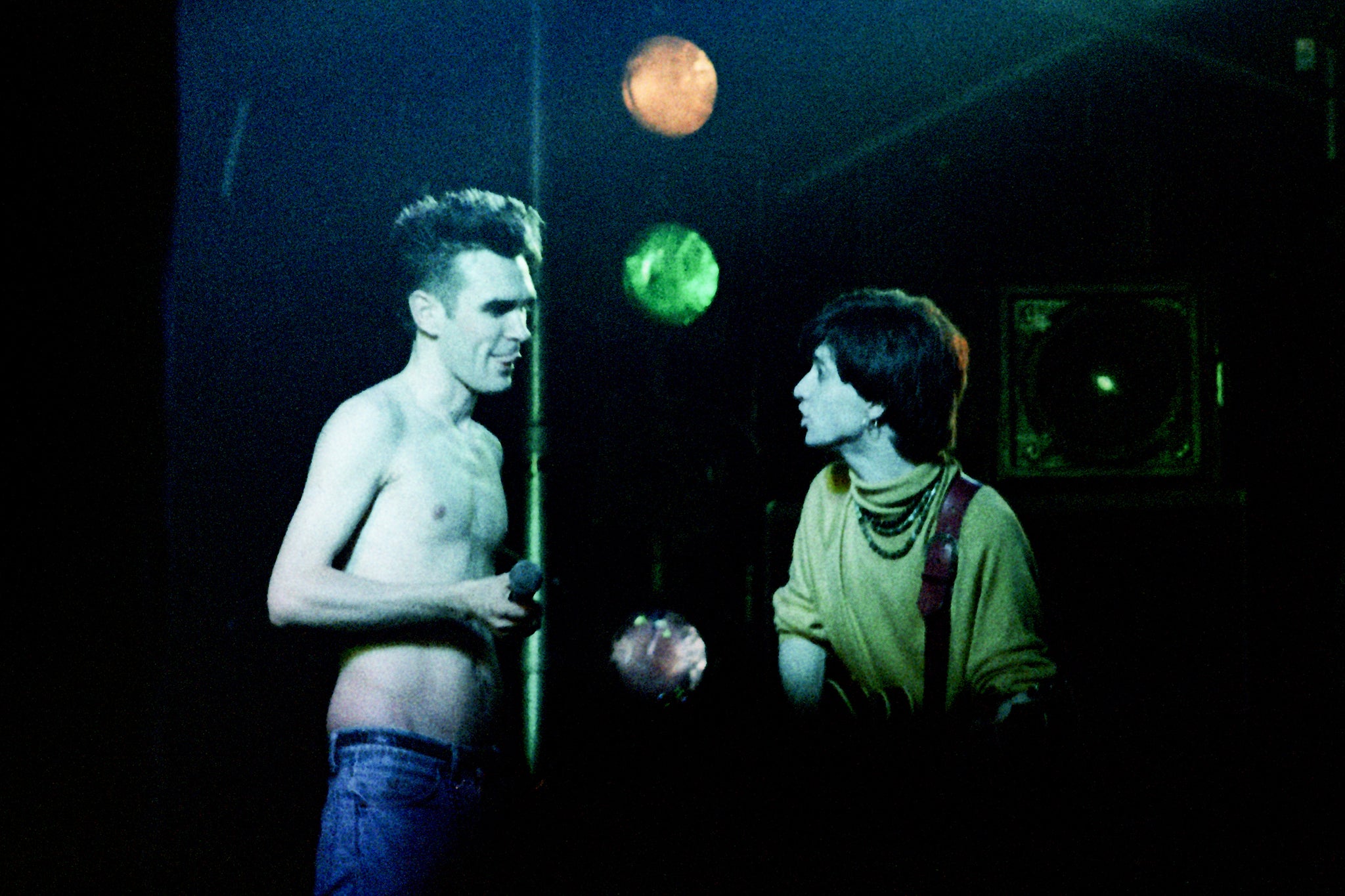

The band were understandably pumped with self-belief. It was just two years since Marr had turned up at Morrissey’s front door in Stretford – having met him at a Patti Smith gig four years earlier – to invite him to form a band. And just one year since Marr had pinned Rough Trade’s Geoff Travis against his office wall and insisted he listen to a demo of “Hand in Glove”, which Travis then released as the band’s debut single. In that time, they’d built a fervent fanbase thanks to sessions for the BBC, an enthusiastic music press, and the spectacle of their live shows – which exploded all traditional rock’n’roll machismo and bravado: Morrissey clad in thick-rimmed NHS specs, oversized shirts, and a hearing aid. He was a socially awkward misfit flaunting his outward flaws as symbols of his inner ones: an icon for the fragile and lost.

The buzz building around the band meant the pressure was on. “There was this sweet spot, back then when charts mattered, that the majors rested having had a good Christmas, and indies felt like they could get noticed early in the new year,” says Richard Cook, then production manager at Rough Trade. “There was an incredible momentum around the band at the time and increasing amounts of media attention. So, the aim from [them] properly signing with ‘This Charming Man’ was to hit the start of ’84.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

To this end, The Smiths were dispatched to Elephant Studios in Wapping with The Teardrop Explodes’ Troy Tate as producer in an almost Saharan late summer. “It was absolutely sweltering,” Joyce recalls of those basement sessions; it was hard to keep their instruments from melting out of tune. “We were in a Renault Master van with a sliding door at the side and each night when we finished recording and we were driving back, we had that open because it was sultry, it was oppressive.”

With Morrissey and Marr sharing the helm alongside Tate, the tracks went down easy. “In terms of arrangement, in terms of sound, [Tate] wasn’t really a hands-on producer,” Joyce explains. “The songs sounded great as they were… there were no obvious howlers in there where you thought, ‘That’s much too long’ or ‘This isn’t right.’ Also, when you’re faced with somebody that’s as good as Johnny, if you come in and start saying, ‘That sound just doesn’t work, maybe it would sound better with this kind of guitar sound’, you’ve got to be right.”

Listen back to bootlegs of those 14 tracks, a collection that has since become known as the Troy Tate sessions, and a sense of unfinished demo leaps out. Joyce’s drumming sometimes over-dominates, Morrissey’s vocals – possibly just incomplete guide tracks – are often buried. The whole thing has the thin feel of suburban garage. When Tate’s recordings were handed to Roxy Music producer John Porter to remix, Porter found them unsalvageable and offered to re-record the album himself. Morrissey agreed, and his Musketeer bandmates fell into line. “I could hear myself that the mixes sounded underproduced and were not the finished article that we needed as our introduction to the world,” Marr wrote in his autobiography. Joyce, though, has a soft spot for the album’s gestational version.

“I sway in and out with this because sometimes I’ve been not sure and sometimes, I think in hindsight it’s a better recording,” he says. “But everybody has to be happy… I just think there was a slight frustration from us all that it didn’t sound absolutely mind-blowing, because we thought it did live, in terms of what we were playing. So surely it should sound better when you go to the studio and record it.”

Johnny Marr was around, and I think the drummer might have been around, but it was mostly Johnny, who was a nice guy, and Morrissey kinda brewing away in the corner

The iron, however, was heating up by the minute. “This Charming Man” was scheduled for a single release in the autumn and time wasn’t The Smiths’ ally. Sessions were swiftly scheduled at West London’s Matrix studios in September – this time with Porter. “John Porter [was] a very different animal,” says Joyce. “More forthright in his views of what he wanted to hear and how he thought his expertise could be used in terms of changing elements of what we had. I felt that we were more, not bossy towards Troy, but that we were more in control of what we were trying to do. I felt with John that was relinquished to a certain extent.”

He cites Porter simplifying the drum part on “What Difference Does it Make?” as an example – so as not to overcomplicate an already busy arrangement. “John – very clever, very smart idea – said to me, ‘Look, if you put it down straight I guarantee it will be a hit. And how about when you play live, you can play it with that more skipping beat?’” he recalls. “I went with that because I felt like what’s the point of having a producer if they just come in and say it sounds fine? [The finished song] sounds great, it sounds okay, but I do prefer the [Tate] version of that track.”

An unexpected presence on the album is Paul Carrack (formerly of Squeeze and later Mike + The Mechanics) who played Hammond organ during overdub sessions at Eden Studios. Living locally to the studio, he’d often be called in to play “odds and sods” on tracks recorded there. “I think I ended up playing on three or four tracks,” he says. “Johnny Marr was around, and I think the drummer might have been around, but it was mostly Johnny, who was a nice guy, and Morrissey kinda brewing away in the corner.” Carrack isn’t sure Moz particularly approved of the Hammond part. “I think his comment was that it sounded a bit like [Wurlitzer legend] Reginald Dixon on acid. I tried to take the comment as a compliment [although] I’m not sure if it was meant as one.”

Porter was proven right about “What Difference Does it Make?”. In October, “This Charming Man” was released to gasping critical acclaim for its Manc-meets-Motown dynamic and Wilde-worthy lyrics, in which Morrissey is rescued from a remote bicycle accident by a flirty charmer in a leather-clad motor. It would come to represent the quintessential early Smiths song and become a formative, inspirational indie pop classic. “The second I heard ‘This Charming Man’, everything made sense,” Noel Gallagher said in 2007. Yet that single only reached No 25 on the charts. It was the following January when The Smiths scored their first Top 20 hit with Porter’s version of “What Difference…”

Nonetheless, The Smiths still weren’t completely satisfied with the finished record. “It was great just to have an album of those songs that we loved,” says Joyce, “[but] I’m just not a big fan of some of those sounds that are on there. It sounds like The Smiths tamed rather than a kind of aggressive, direct power. It was as though that had been taken away and it was more of a studio album.”

The band’s dissatisfaction with The Smiths was a key driver in the 1984 release of a compilation of early BBC sessions titled Hatful of Hollow, now regarded as one of the greatest albums of its era. Here, the swift recording process had better captured the punkish urgency of their music, and deserved prominence was afforded to B-sides that would come to rank amongst their finest achievements: the yearning “Please, Please, Please, Let Me Get What I Want” and the wonderfully crepuscular “How Soon is Now?”. “It’s very old-school,” Joyce says of the radio session recording. “Get in there, record them, overdub, mix, see ya, next! And I think that had more of a live feel, whereas the sounds that were used on the first album, it just sounds a bit more sanitised.”

The Smiths weren’t the only ones to find issues with their debut. Tabloids ran spurious stories about “Reel Around the Fountain” and “The Hand That Rocks the Cradle” having supposedly paedophilic undertones, an allegation that the band firmly denied. And the subject matter of “Suffer Little Children” – an unflinching, mournful lament for the victims of Moors murderers Ian Brady and Myra Hindley in the early Sixties – saw the album withdrawn by Boots and Woolworths after the grandfather of one of the children named in the song heard it on a pub jukebox and complained that The Smith were commercialising atrocities. Morrissey met with him and other victims’ family members; he went on to establish a friendship with Lesley Ann Downey’s mother, Anne West, once his honourable intentions were made clear.

It’s a pretty damn dark recording of an incredibly harrowing incident

“When it was written, it was to make people aware that the shocking nature of what happened wouldn’t be forgotten,” Joyce says. “It’s a pretty damn dark recording of an incredibly harrowing incident. Is popular music a vehicle to do that? Some people thought maybe not, but as far as I was concerned if it’s not in there, then where should it be? Should it always be, ‘She met me, she left me, she don’t love me and I’m sad’?”

That The Smiths dared to broach such devastating themes, and with sympathy rather than fascination, was part of what made the album so affecting. It teased at the corners of taboos and glanced wistfully into the depths of despair. Thus, a multitude of sensitive, shunned and misunderstood outsiders – rarely so proudly represented in music before – flocked to it for catharsis, emancipation, empathy and belonging. The record shot to No 2, and a new era of indie guitar music was born.

“It made guitars prominent again, certainly in the core labels of the independent scene,” says Cook. “Mute, Factory and 4AD, they didn’t really have guitar bands. And it stimulated outsiders to think, ‘Let’s give it a go’, and I think that was refreshing.”

That being said, Joyce prefers The Smiths’ 1987 swansong Strangeways, Here We Come to their debut. “And I think I’m right in saying that it’s Johnny, Morrissey and Andy’s [favourite] too,” he says. “But people say the first album’s majestic, one of the best albums they’ve ever heard. It’s like talking about days of the week. ‘Thursday’s brilliant’ or ‘Friday’s miles better’ – ‘What about Monday though?’”

For Joyce, the true impact and legacy of The Smiths lies in the fact that it’s the band’s initial emergence as a complete package. Morrissey’s enthralling lyrical content and stage persona, swinging gladioli around to “This Charming Man” on Top of the Pops is the indie generation’s very own “Starman” moment. The cool yet studious image. And the “frighteningly good” musicianship of Marr and Rourke. “We were kids,” Joyce says, still amazed at the band’s immaculate aesthetic 40 years on. “With The Smiths everything was covered. There wasn’t anything else that you’d want for in a band.” What difference did it make? A world.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks