Silent at last: Pete Seeger, the voice of US protest

The death of Pete Seeger – folk singer, agitator and icon of the American left – marks the end of a cultural era. Bart Barnes looks back on the life of an ‘inconvenient artist’ who provided the soundtrack for the civil rights movement

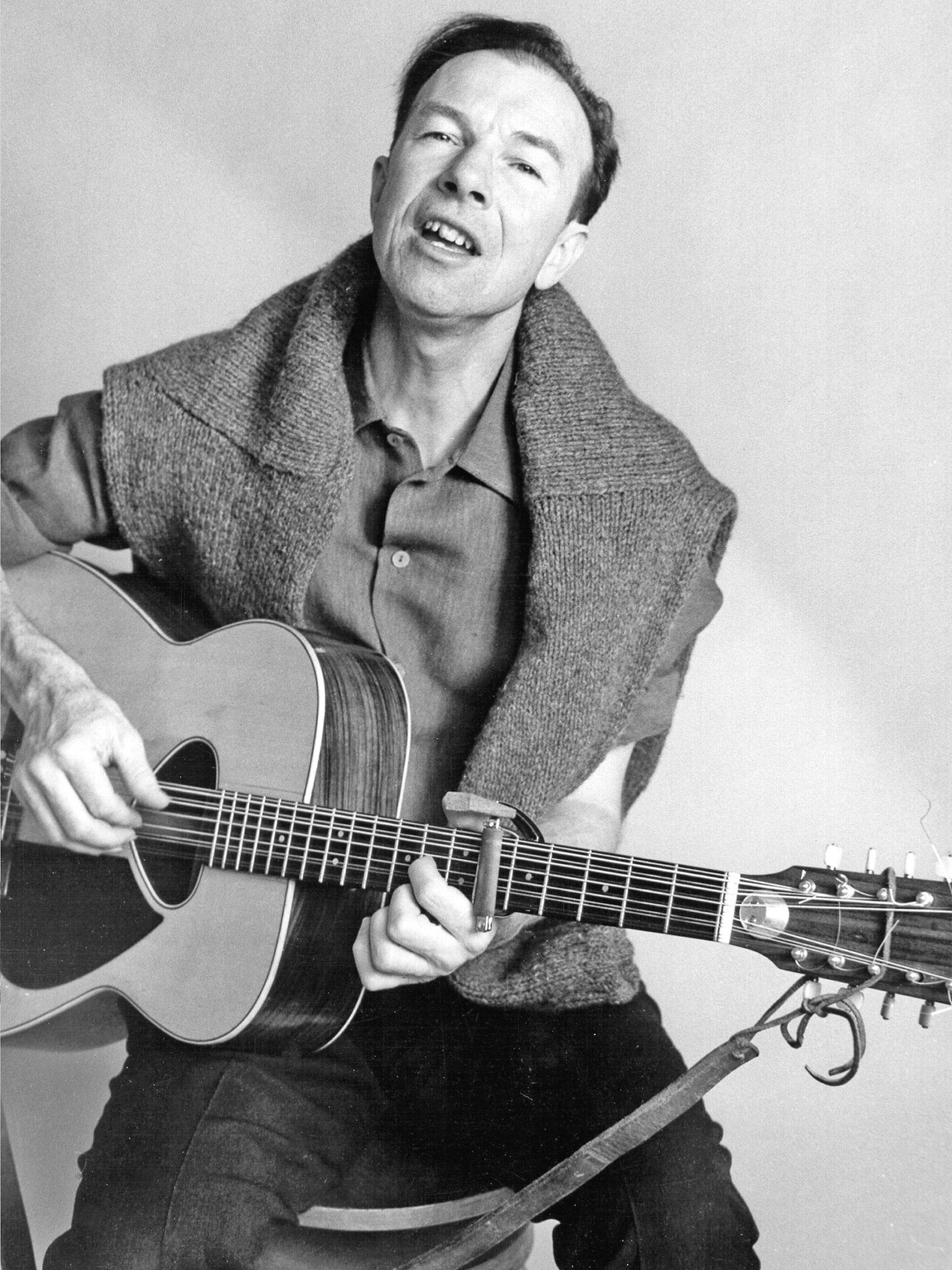

For more than 50 years, Pete Seeger roamed America, singing on street corners and in saloons, migrant labour camps, hobo jungles, union halls, schools, churches and concert auditoriums. It was that spirit – the effervescence of a musical and political missionary – which has resulted in the tributes to the 20th-century troubadour on news of his death at the age of 94.

The singer, who died on Monday night after being hospitalised in New York for six days, inspired and led a renaissance of folk music in the United States with his trademark five-string banjo and songs of love, peace, brotherhood, work and protest.

Tall and reed-thin, Seeger was a recognisable figure for generations of listeners. And with dozens of top-selling records and albums, he became one of the most enduring and best-loved folk singers of his generation. He helped write, arrange or revive such perennial favourites as “If I Had a Hammer,” “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” and “Kisses Sweeter Than Wine” – and popularised the anthem of the civil rights movement, “We Shall Overcome”.

Seeger was one of the few remaining links to two of the 20th century’s early giants of American folk music: Huddie Ledbetter, the ex-convict better known as Lead Belly, and Woody Guthrie, the songwriter from Oklahoma.

It was from Guthrie that Seeger learned to express political and social criticism through music and song – and it was that awareness, as much as its artistic representation, which led Barack Obama to laud his work yesterday.

“Once called ‘America’s tuning fork’, Pete Seeger believed deeply in the power of song,” said the US President. “But more importantly, he believed in the power of community. To stand up for what’s right, speak out against what’s wrong, and move this country closer to the America he knew we could be.”

Bruce Springsteen, who named an album after Seeger and considered him a major influence, said yesterday: “From the Civil Rights movement to the anti-war movements Pete and his songs have been there on the front lines. Like a ripple that keeps going out from a pond Pete’s music will keep going out all over the world spreading the message of non-violence and peace and justice and equality for all.”

Springsteen once described Seeger as “a walking, singing reminder of all of America’s history… a living archive of America’s music and conscience, a testament to the power of song and culture to nudge history along, to push American events towards more humane and justified ends.”

Political dissent had been a tradition in Seeger’s family for generations. A great-grandfather was a 19th-century abolitionist. The World War I poet Alan Seeger, who wrote “I Have a Rendezvous With Death”, was an uncle.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

His educational background was traditional, however, especially for the son of a First World War conscientious objector. He attended boarding schools in Connecticut before enrolling in 1936 at Harvard University, where one of his classmates would go on to become President: John F Kennedy.

Uninterested in his studies and disillusioned by the social havoc wrought by the Depression, however, Seeger dropped out midway through his second year. For a period at Harvard, he attended meetings of the Communist Party.

Dissent and left-wing expression became hallmarks of his artistic repertoire. During the anti-Communist “Red Scare” of the 1950s, he was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

“I have sung in hobo jungles, and I have sung for the Rockefellers, and I am proud that I have never refused to sing for anybody,” he told the committee. “I have never done anything of any conspiratorial nature... I love my country very deeply.”

President Bill Clinton described Seeger in 1994 as “an inconvenient artist who dared to sing things as he saw them.” The news media sometimes called him a “pied piper of musical dissent”. And by the dawn of the new millennium, he had become the widely acknowledged, if unofficial, grand old man of American folk music.

He regarded folk songs as music meant to be sung by crowds and bonded with audiences around the world by inviting them to sing with him. During a performance at Moscow’s Tchaikovsky Concert Hall, he led an audience of 10,000 Russians in a four-part harmony of “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore”.

“I just tap out a beat, pick a few chords and say, ‘Come on, you folks know this old tune.’ Pretty soon the audience’ll be singing the song to me,” Seeger once said.

“You can’t sit idle at a Pete Seeger concert,” folk-music collector and performer Ralph Rinzler wrote in The Washington Post in 1972.

“Audiences for 30 years have sung, clapped and risen to their feet with enthusiasm. Pete strides onstage, loosens his tie, picks the five-string, adding other instruments as he talks, spins yarns, preaches and sings songs of the nation’s and the world’s people — new ballads, old ones, lyrical laments and hard driving, keen-edged cutters.”

Whether leading a singalong of college students or at a formal concert, Seeger said, he tried to recreate the atmosphere in which his songs were first sung. He sang in a light, pleasing baritone. His goal, he said, was “to put a song on people’s lips, instead of just in their ears”.

Chance and happenstance historically have driven the evolution of folk music, and so they did for many of the most popular tunes associated with Seeger. “If I Had a Hammer”, for example, began as a tune Seeger made up at the piano one afternoon in 1949 with Weavers colleague Lee Hays.

It was known in its original form as “The Hammer Song” and did not achieve popularity when the Weavers – the band he formed in the 1940s with three other singers, Hays, Ronnie Gilbert and Fred Hellerman – recorded it. But the lyrics drew the attention of federal investigators who during the 1950s thought that, used in songs, words such as “peace” and “freedom” were codes for left-wing subversives and communists.

As the Weavers became more popular, a magazine known as Red Channels named the group – and Seeger in particular – as Communist Party sympathisers.

At a time when Senator Joseph McCarthy regularly made headlines with charges of Communist infiltration of government agencies, academia and the entertainment industry, there were swift calls for Seeger and his comrades to be blacklisted from professional engagements. In short order, almost all the Weavers’ nightclub, concert, radio, TV and recording engagements evaporated. Seeger’s public career was abruptly curtailed.

In 1955, the House Un-American Activities Committee began an investigation of Communist influence in professional entertainment and subpoenaed Seeger. He volunteered to discuss his music at length with the committee, and he offered to sing his songs. But he declined to answer questions about political associations or whether certain songs were sung at Communist gatherings, and he declined to invoke his constitutional right of protection from self-incrimination. “I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked, especially under such compulsion as this,” he said.

Convicted of contempt of Congress, he was sentenced to a year in jail. After a prolonged appeal process, the conviction was overturned in 1962 because of a technical flaw in the indictment. The government never retried him for the offence.

“I apologise for once believing Stalin was just a hard driver, not a supremely cruel dictator,” he told The Washington Post in 1994. “I ask people to broaden their definition of socialism. Our ancestors were all socialists: you killed a deer and maybe you got the best cut, but you wouldn’t let it rot, you shared it. Similarly, I tell socialists, every society has a post office and none of them is efficient. No post office anywhere invented Federal Express.”

With the resurgence of folk music later in the 1960s, Seeger’s music became popular again. His concert and recording opportunities swelled. Indeed, it was not until Peter, Paul and Mary recorded a revised version of “The Hammer Song” in 1962 that the song become a hit. It remained a centrepiece of Seeger’s concerts.

“Very few people sing it as I originally wrote it,” Seeger said later. “I call this the folk process, and I’m delighted to see it carrying on.”

Until the end of his life, he remained a beloved figure. The broad public affection for him was on full display in 2009 when, at 89, he joined Bruce Springsteen in a rendition of “This Land Is Your Land” at a concert on the Lincoln Memorial during President Obama’s inaugural festivities. As recently as this year he was nominated for a Grammy in the spoken word album category for “The Storm King”.

“I call them all love songs,” Seeger once said of his music. “They tell of love of man and woman, and parents and children, love of country, freedom, beauty, mankind, the world, love of searching for truth and other unknowns. But, of course, love alone is not enough.”

@The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks