The Beatles' 'Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band' at 50: still full of joy

Fifty years on from the Summer of Love, Jon Pareles considers how one of the most era-defining albums has aged – and how it still astounds today with its whimsical nature

Half a century after its release, the Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is a relic of a vanished era. Like a Fabergé egg or a Persian miniature, it speaks of an irretrievable past, when time moved differently, craftsmanship involved bygone tools and art was experienced more infrequently and with fewer distractions.

It’s an analogue heirloom that’s still resisting oblivion — perhaps because, even in its moment, it was already contemplating a broader sweep of time. The music on Sgt Pepper reached back far before rock as well as out into an unmapped cosmos, while its words — seesawing between Paul McCartney’s affability and John Lennon’s tartness — offered compassion for multiple generations.

We simply can’t hear Sgt Pepper now the way it affected listeners on arrival in 1967. Its innovations and quirks have been too widely emulated: its oddities long since absorbed. Sounds that were initially startling — the Indian instruments and phrasing of George Harrison’s “Within You Without You”, the tape-spliced steam-organ collage of “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite” and the orchestral vastness of “A Day in the Life’”— have acquired a patina of nostalgia.

Sgt Pepper and its many musical progeny have blurred into a broader memory of ‘psychedelia,’ a sonic vocabulary (available to current music-makers via sampling) that provides instant, predigested allusions to the 1960s. Meanwhile, the grand lesson of Sgt Pepper — that anything goes in the studio — has long since been taken for granted.

Sgt Pepper has been analysed, researched, oral-historied and dissected down to the minute differences between pressings, and because the Beatles industry never misses an anniversary, it has been repeatedly reissued. The 50th-anniversary deluxe version is exhaustive. It has been remastered once again to give the album a broader sound stage and crisper detail, giving more separation to individual voices and instruments. For the older blend, it also includes the mono-mix from 1967.

The new box rightfully incorporates “Strawberry Fields” and “Penny Lane”, the masterpieces recorded alongside Sgt Pepper but released before the album. It also has outtakes, comprehensive reading material, video clips from 1967 and a documentary about making the album. (The anecdotes are now familiar because the film was done for the album’s 25th anniversary.)

Sgt Pepper was not universally adored when it appeared. The New York Times panned it, not entirely incorrectly, as “busy, hip and cluttered”. As pop tastes have swung between elaborate musical edifices and back-to-basics reactions, Sgt Pepper has been by turns embraced, reviled and simply ignored.

But now that rock itself is being shunted toward the fringes of pop, it’s a good time to free Sgt Pepper from the burden of either forecasting rock’s eclectic future or pointing toward a fussy dead end. It doesn’t have to be “the most important rock & roll album ever made,” as Rolling Stone declared in 2012, or some wrongheaded counter-revolutionary coup against ‘real’ rock‘n’roll. It’s somewhere in between, juxtaposing the profound and the merely clever.

Although the album as a whole is synergistic, song by song it’s a mix of milestones, like “A Day in the Life” and “Within You Without You”, with meticulously wrought baubles like “Lovely Rita” and “Good Morning Good Morning”. Two of its most remarkable songs, “Strawberry Fields” and “Penny Lane”, aren’t even on the album. But with 50 years of hindsight, Sgt Pepper remains a joyful, whimsical and revelatory experiment. Even the album’s slightest songs are full of musical and verbal twists.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

For people who, like me, heard the album brand new in 1967, Sgt Pepper remains inseparable from its era. It was released on 2 June 1967, the beginning of the Summer of Love. It was a time of prosperity, naive optimism and giddy discovery, when the first baby boomers were just reaching their 20s and mind-expanding drugs had their most benign reputation.

In 1967, candy-coloured psychedelic pop and rock provided a short-lived but euphoric diversion from conflicts that would almost immediately resurface: the Vietnam War and America’s racial tension. Sgt Pepper remains tied to that brief moment of what many boomers remember as innocence and possibility — the feeling captured perfectly in “Getting Better”, even as Lennon taunts that “it can’t get no worse”.

Yet for the Beatles, that instant of cultural innocence was a strategic artistic opening. By 1967, the Beatles were by no means ingenuous. They had already been through exponentially expanding pop stardom, endless screaming crowds and the fierce American backlash against Lennon’s flippant 1966 remark that the Beatles were “more popular than Jesus now”.

After three years of hectic touring and recording, and of jaw-droppingly rapid development as songwriters amid the tempest, the Beatles decided to get off the road, where they couldn’t hear themselves play, and to focus on making studio albums. They took five months — an eternity at the time, now barely a pause for a new wardrobe and sponsorship deal — to record the Sgt Pepper album, “Strawberry Fields” and “Penny Lane”.

With “Revolver”, they had embraced studio surrealism and partly jettisoned love songs, and for its successor they would have more time to think and tinker. Yet they still worked amazingly fast, harnessing the era’s primitive technology to pack wild ideas onto a four-track tape. Each Sgt Pepper song creates its own sonic realm, far removed from the live Beatles’ two guitars, bass and drums.

They gave themselves a usefully loose concept. They would become ‘Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’, setting aside all outside expectations of the Beatles and treating the album as a performance complete with canned audience reaction: a theatrical distancing device.

While the Beatles had travelled the world, only “Within You Without You” flaunted the exotic. Mostly, Sgt Pepper’s band was almost provincially British: wandering London in “A Day in the Life”, telescoping an entire middle-class English life (complete with prospective grandchildren) above a music-hall bounce in “When I’m 64”. Stalwart British brass answered the rowdy distorted guitar in Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band; “She’s Leaving Home” is a stately waltz set to a harp and parlour orchestra that might have accompanied high tea. One of the Beatles’ paths forward led through an expanded embrace of the past.

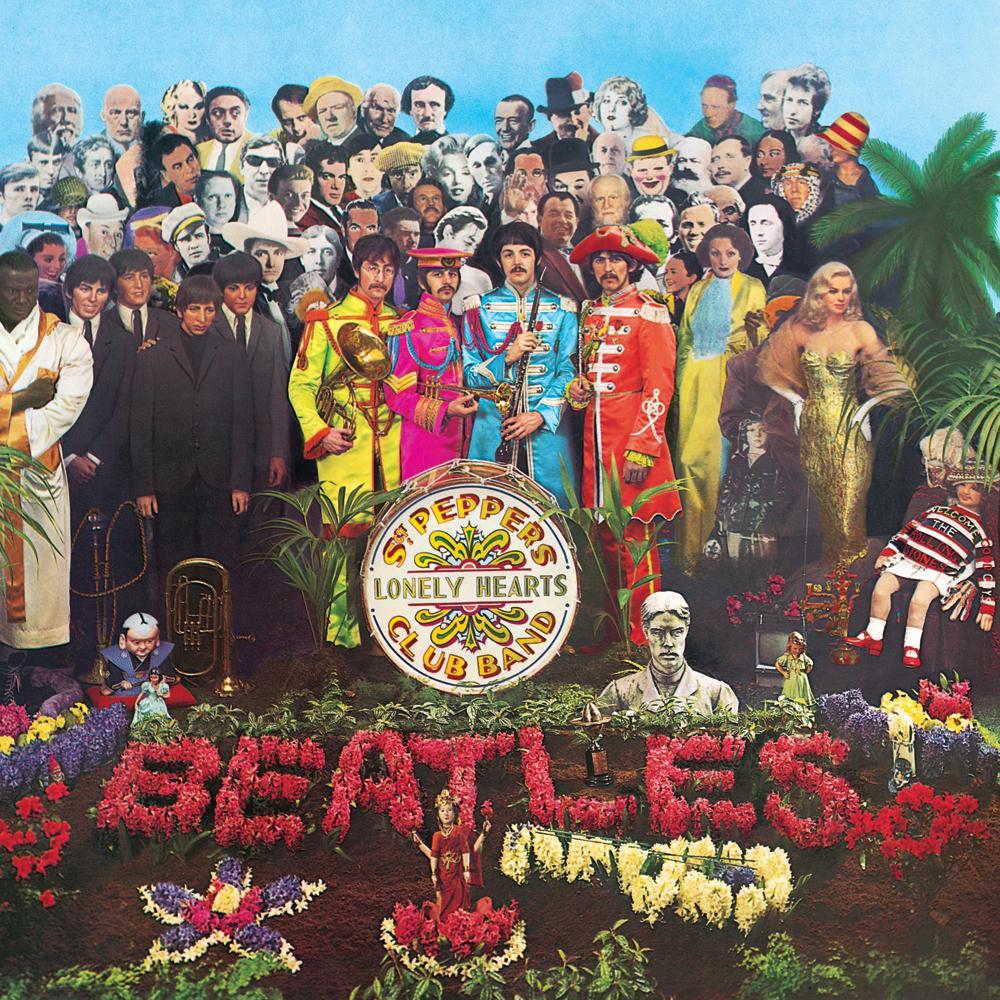

They rejected any generation gap. The album cover set the 1967 Beatles, with their moustaches and shiny mock band uniforms, alongside their suited, mop-topped pop-star wax statues — so recent, yet so distant — and cultural figures like Karlheinz Stockhausen, Sonny Liston and WC Fields, a rightful claim to adult significance. But the LP was also packaged with cardboard cutouts — a moustache, military stripes — like something for children. While the Summer of Love nurtured hippie dreams of creating a new world, the Beatles reminded listeners of how entrenched the old one was, and how comforting.

But at the same time, Sgt Pepper gazed forward in sound and sense. The Beatles, and their producer George Martin, concocted eerie, unforgettable sounds from hand-played instruments and analogue tape tricks; “Strawberry Fields”, which miraculously interweaves two arrangements of the song in two keys, remains a marvel of internal disorientation. And despite all the vintage references, Sgt Pepper situated its songs in the present: sometimes a rushed, workaday world and sometimes a mind-altered escape.

The album’s magnificent, sobering finale, “A Day in the Life”, understood — and anticipated — the ethical and emotional ambiguities of a world perceived through mass media, even back when the news media was just newspapers, radio and television.

Sgt Pepper had an immediate, short-lived bandwagon effect, as some late-1960s bands sought to figure out how to make those strange Beatles sounds, and others got more studio time and backup musicians than they needed. Artistic pretensions also notched up. And the pendulum started its long-term swings: progressive rock and corporate rock would be swatted back by punk and disco, hair metal would be blasted by grunge and hip-hop. The studio artifice that Sgt Pepper daringly flaunted has long since become commonplace.

Yet while Sgt Pepper has been both praised and blamed for raising the technical and conceptual ante on rock, its best aspect was much harder to propagate. That was its impulsiveness, its lighthearted daring, its willingness to try the odd sound and the unexpected idea. Listening to Sgt Pepper now, what comes through most immediately is not the pressure the Beatles put on themselves or the musician challenges they surmounted. It’s the sheer improbability of the whole enterprise, still guaranteed to raise a smile 50 years on.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments