Eikoh Hosoe: Capturing the 20th century’s darkest sins

Eikoh Hosoe’s memories of the Hiroshima bomb inspired his stark, transgressive images and made him one of Japan’s most refined photographers. A new book and retrospective reflect on his extraordinary career

Like so many of his generation, Eikoh Hosoe’s life was irrevocably changed by the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings in 1945, when he was 12 years old. “A single bomb had killed tens of thousands of people,” he recalls thinking in a new photo book, Eikoh Hosoe. “What would happen if ten planes came and dropped ten bombs, or one hundred planes dropped a hundred atomic bombs...? Merely imagining that made my hair stand on end.”

Hosoe’s confrontation with the dark potential of humanity made him one of Japan’s most influential photographers. After the war, he became known for his transgressive, sexually-charged work which looked unflinchingly at human irrationality and obsession. He nurtured other artists’ careers too, collaborating with dancers and filmmakers, as well as teaching, curating and founding an art journal and a photographic cooperative.

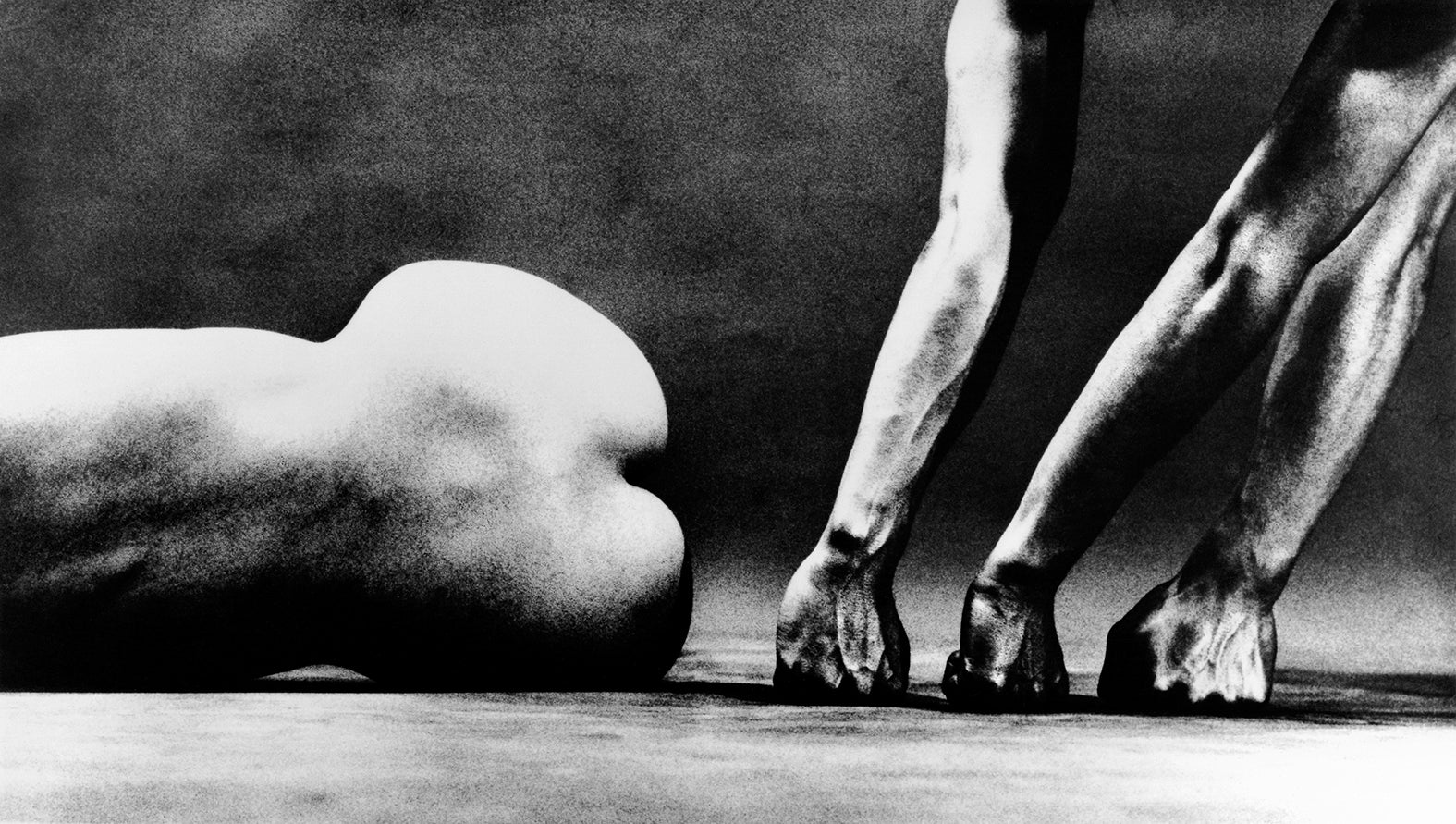

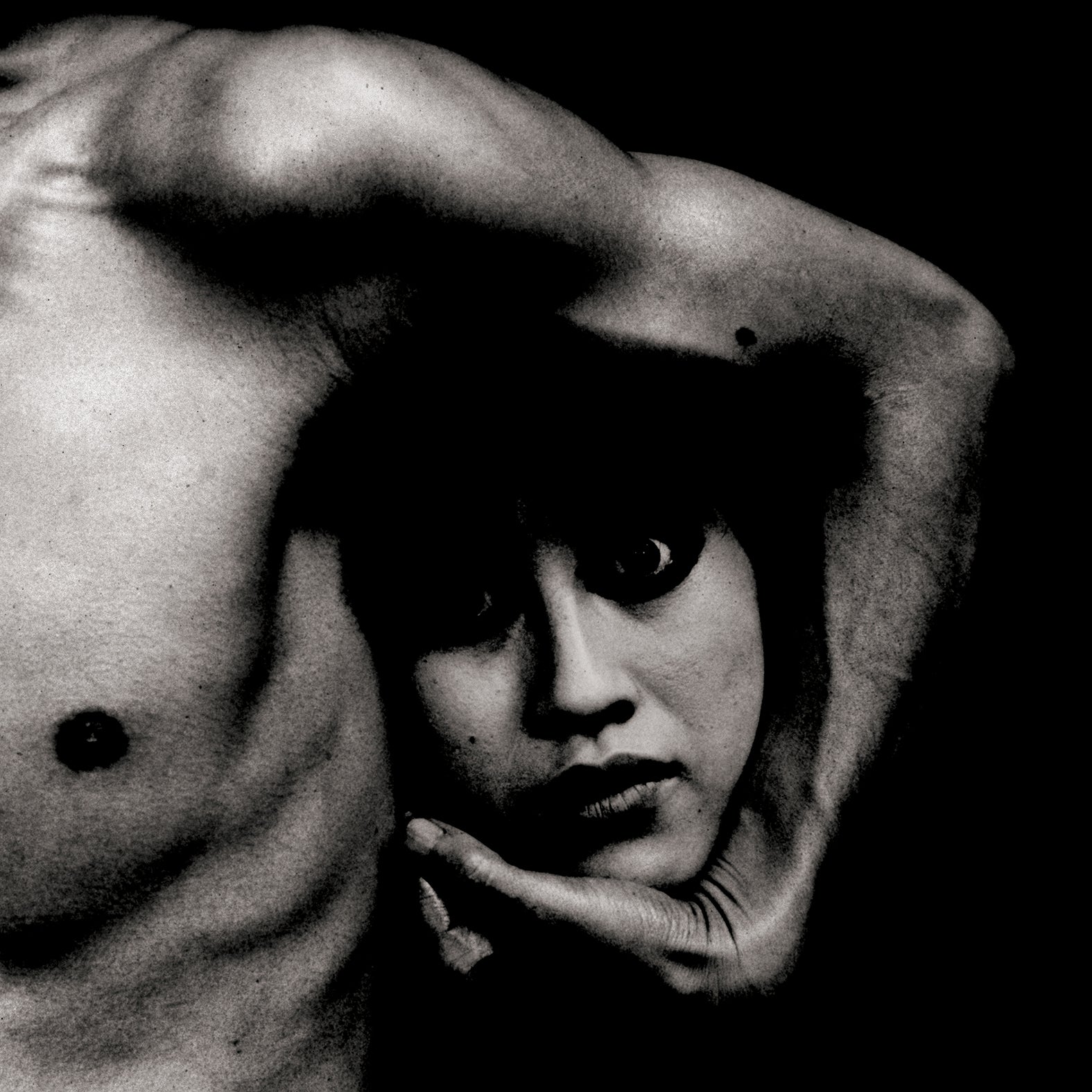

Now the new photobook and a retrospective at the Kiyosato Photographic Arts Museum in Japan look back on the 88-year-old’s extraordinary life and career. From his early works, like his 1959 collaboration with butoh dancer Tatsumi Hijikata called Man and Woman, Hosoe defied the contemporary fixation on social realism. Instead, he found an expression of truth through stark black-and-white compositions. In front of his camera, bodies are presented in their rawest form – skeletal, genderless and abject but still powerful.

“Through exploratory poses, unexpected framing, complex material layers, and careful image printing, the Man and Woman series embodies visual gender-play,” writes Christina Yang in Eikoh Hosoe. “In attempting to detach gender norms from the camera’s gaze, Hosoe’s images resist fixed binaries – male or female, animal or human, flesh or land – imagining something other, nearly primordial, objectified.”

He would continue to explore his fascination with taboo and liberation in the latter half of the 1960s. His Kamaitachi series, named after mythical kamaitachi earth spirits, depicts memories of being evacuated from Tokyo to rural Yonezawa as a child in 1944. He struggled to work around the “expressive limitations of photography” when recreating childhood memories; his solution was to take Hijikata to his own hometown in Akita and capture him dancing.

The series sees Hijikata leaping across fields and villages, naked or in robes, flocked by village children or alone in the moonlight. “We never shot in Yonezawa, the hometown of my memories, but I never felt the need to be at a specific location; I was satisfied simply to ‘record’ things that felt to me like my ‘memories,’” Hosoe writes.

Collaborations continued to define Hosoe’s photography. He notably worked with controversial nationalist poet Yukio Mishima on the darkly erotic Ordeal by Roses; Mishima would go on to commit seppuku (a form of ritual suicide) after a failed coup attempt in 1970. But mostly, Hosoe continued working with dancers and actors, furthering his exploration of the spaces between portrait, performance and documentary, while nurturing emerging photographers like Daido Moriyama.

Now nearing his ninth decade, his vision of the world remains as stark as ever. “The 20th century has been the most sinful century in human history,” he writes in Eikoh Hosoe. Ultimately though, he believes humanity can learn from the mistakes of the past. He writes that his 1992 series Luna Rossa “ends with a work depicting a scene in which a 20th-century virgin, with keloid scars left on her back from exposure to radiation, hands over an immaculate ‘fruit of love and hope’ to the new life of the 21st century”.

Eikoh Hosoe edited by Yasufumi Nakamori is published by MACK. The Photographs of Eikoh Hosoe: The Theatre Within the Dark Box is at Kiyosato Photographic Arts Museum, Japan until 5 December 2021

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks