Larry Fink on Trump, the 1963 march on Washington and today’s BLM movement

Larry Fink recalls his days photographing the 1960s civil rights movement – and why he can’t quite bring himself to turn his lens on Trump

Fifty-seven years ago, on 28 August 1963, Larry Fink was zooming down the highway from New York to Washington DC, an American flag streaming from the back of his motorcycle. The highway was busy with fellow motorists with the same destination in mind. “Every time we would pass each other by, there would be a tremendous outroar of comradery,” he tells The Independent.

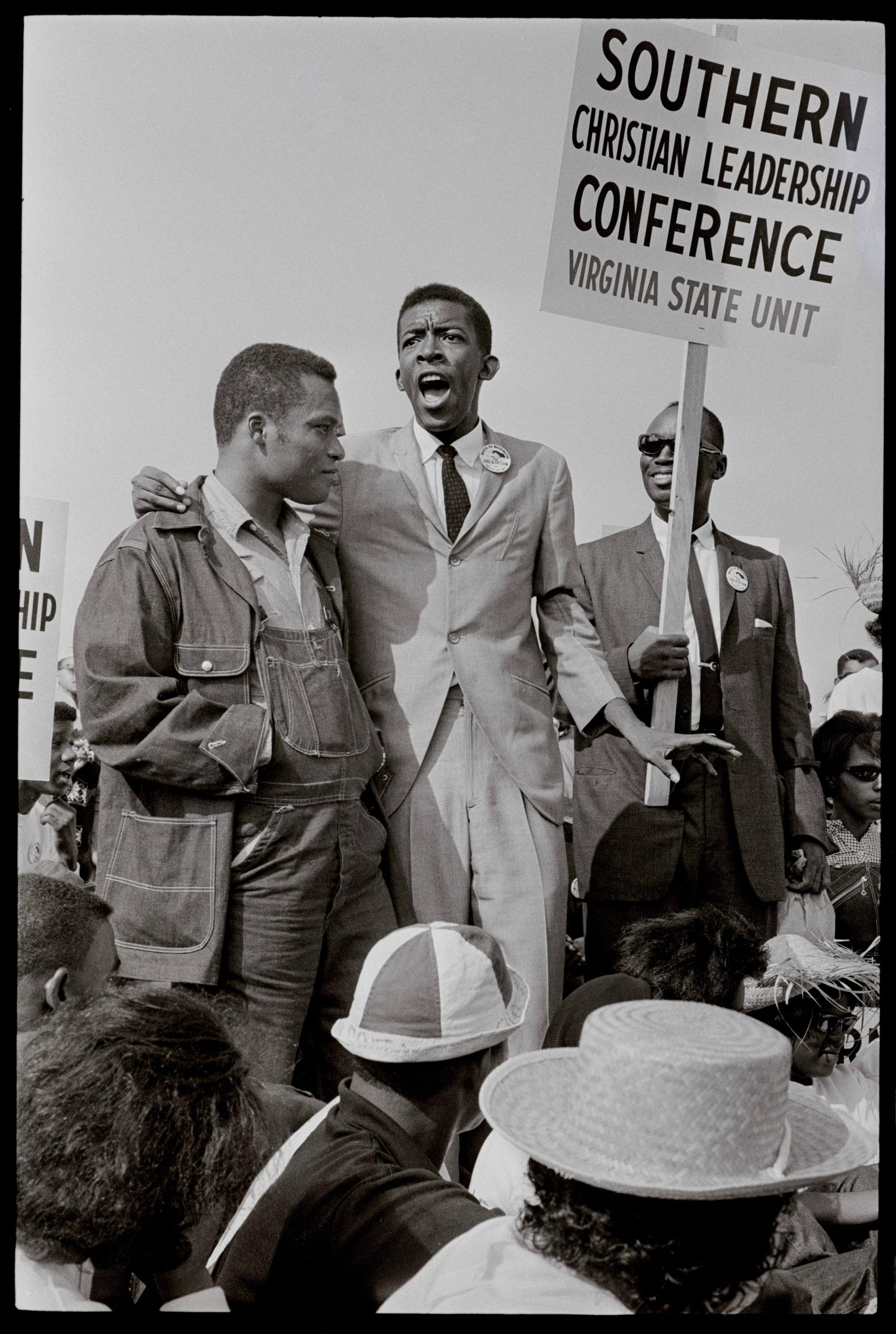

Fink, then a young photographer in his early twenties, was heading to the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. He didn’t know it then, but it would become one of the defining moments of the American civil rights movement. Fink was one of the 250,000 people to gather in the capital that day for a black-organised peaceful march that culminated in Martin Luther King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

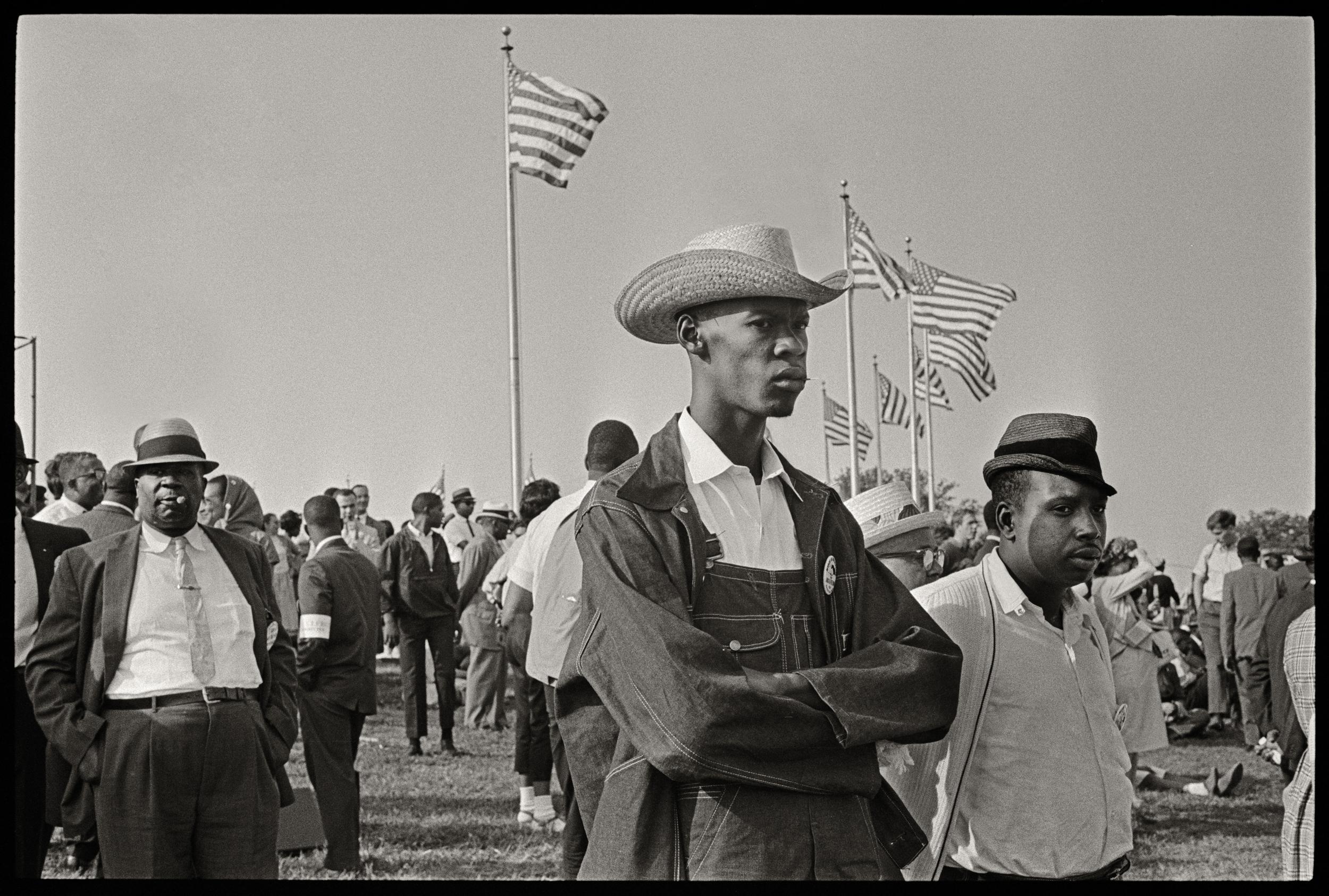

Fink wasn’t on assignment that day. He was at the march as a young Marxist: “Everything I did back then, I felt, was for the revolution,” he says. His photographs are full of compassion for the people around him, and they capture a weary but unwavering determination. In one picture, titled Many Shades of Concern, a southern sharecropper at the march stands watching and waiting with his arms crossed, flanked by a number of American flags. As he gazes ahead, his expression reflects the hardships that bought him to this moment, as much as his hope for change.

Almost 60 years later, as Black Lives Matter protests explode across the US and around the world, it is clear that the dream manifested on that day is still yet to be realised. At 79 years old and vulnerable to the coronavirus, Fink isn’t out on the streets photographing this latest wave of protests. Instead, he is releasing a charity print edition of Many Shades of Concern, with all proceeds going to the Until Freedom Organisation.

He recalls his early involvement with the civil rights movement with joy. “It was a magnificent time,” he says. “The passion that was given to a certain kind of innocence, the sense that there was hope in the air and that freedom could be sustained.”

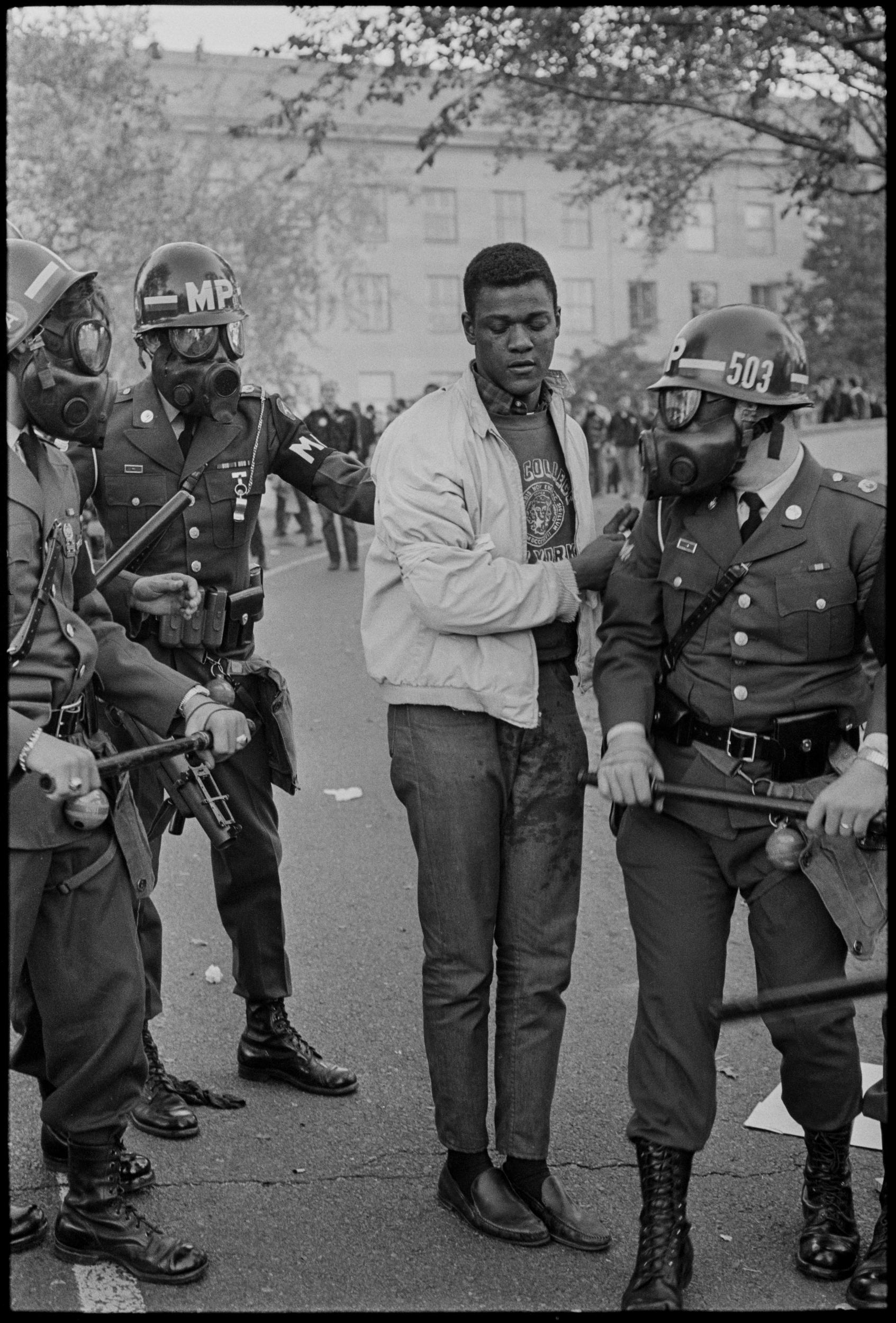

That’s not to say there weren’t some hairy moments. “One time I was in Washington Square Park photographing a big march,” he says. “I was on the sidewalk and all of a sudden a plainclothes policeman came up to me.” As Fink tells it, the policeman hit him over the head with a billy club, punched him in the stomach and crushed his camera. “He threw me in the paddy wagon,” Fink says, “I went to jail for the day.” The same policeman called him a “commie faggot” and told him his life was in danger at a later police tribunal. “For about two years after I was living with a certain degree of paranoia,” he says.

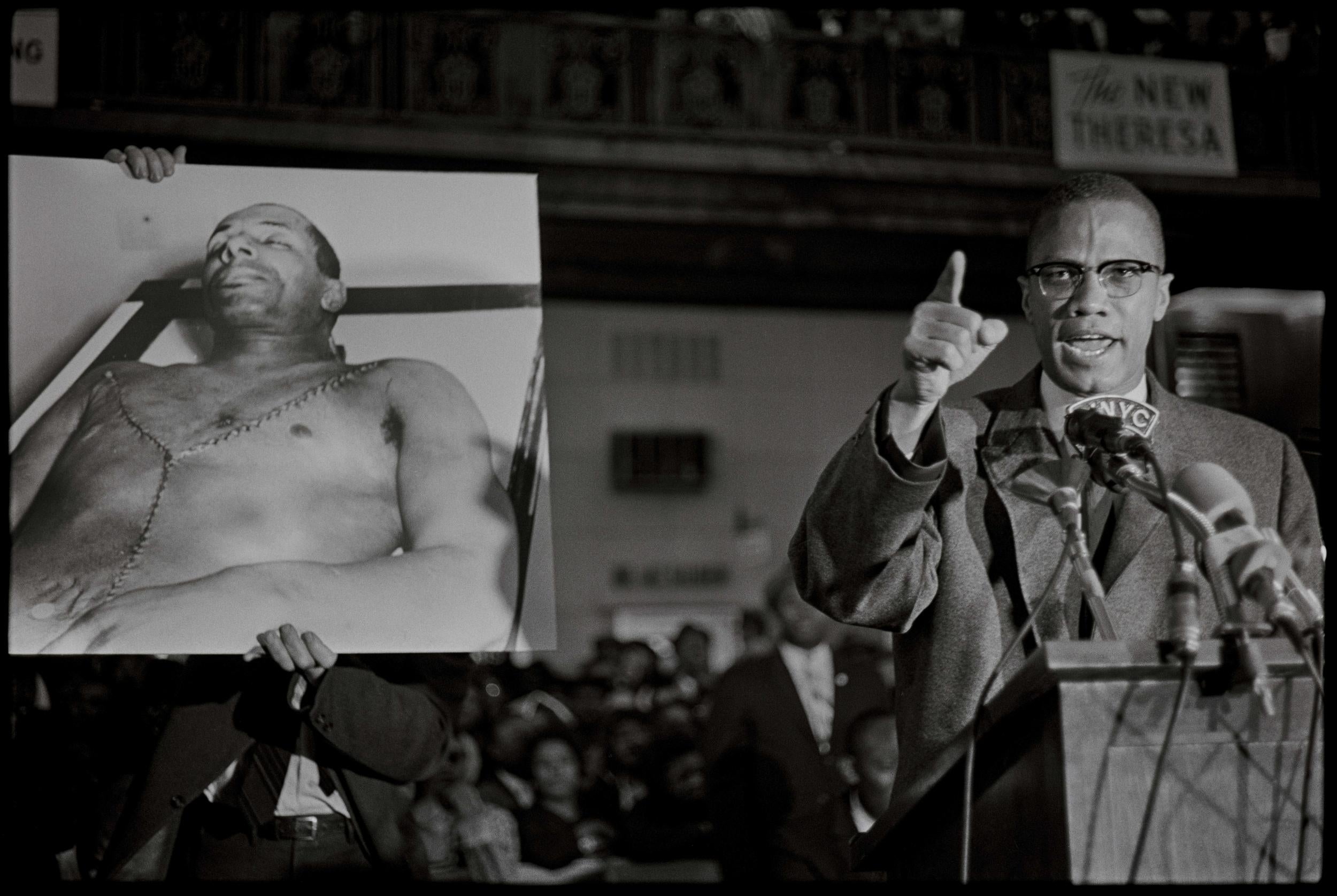

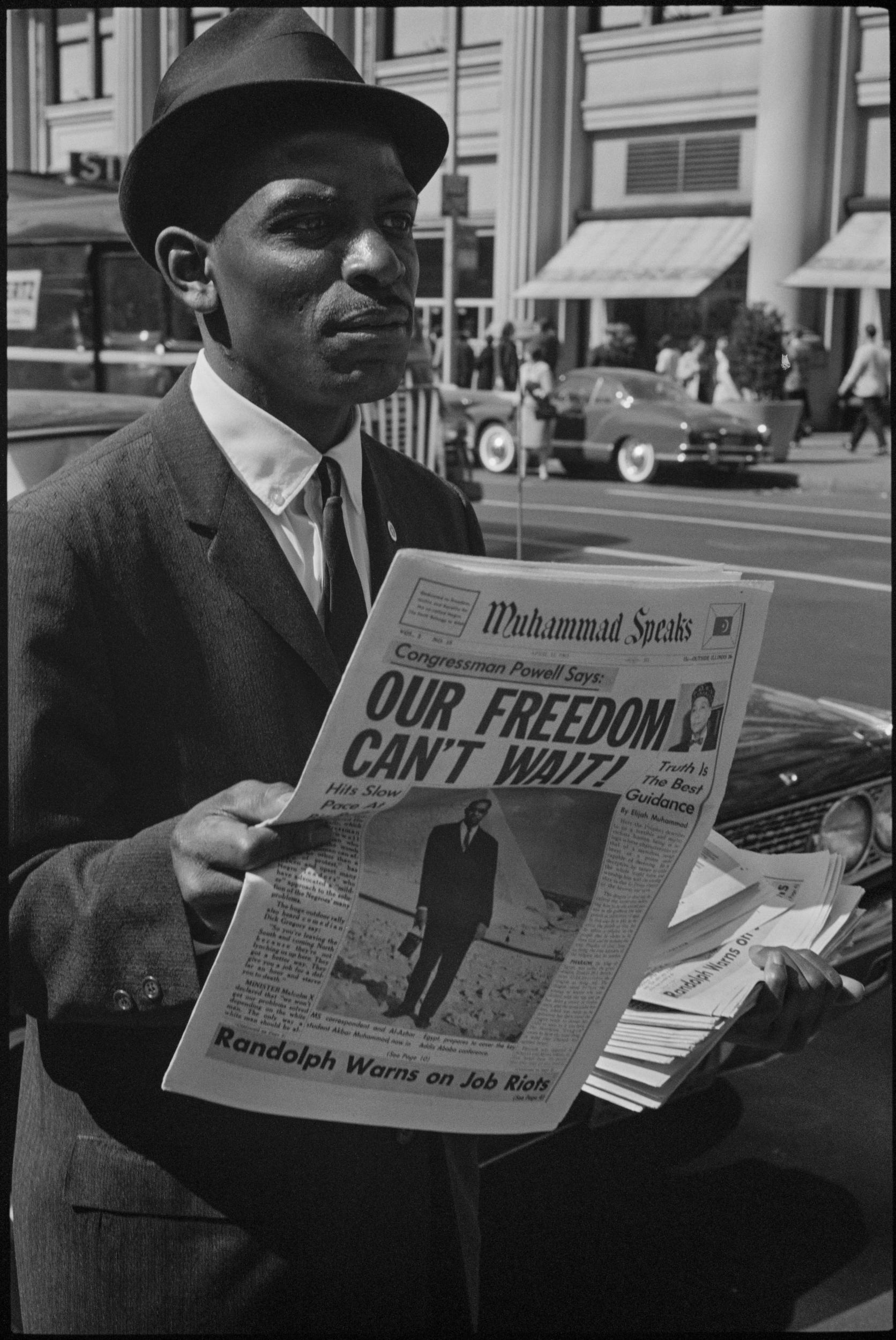

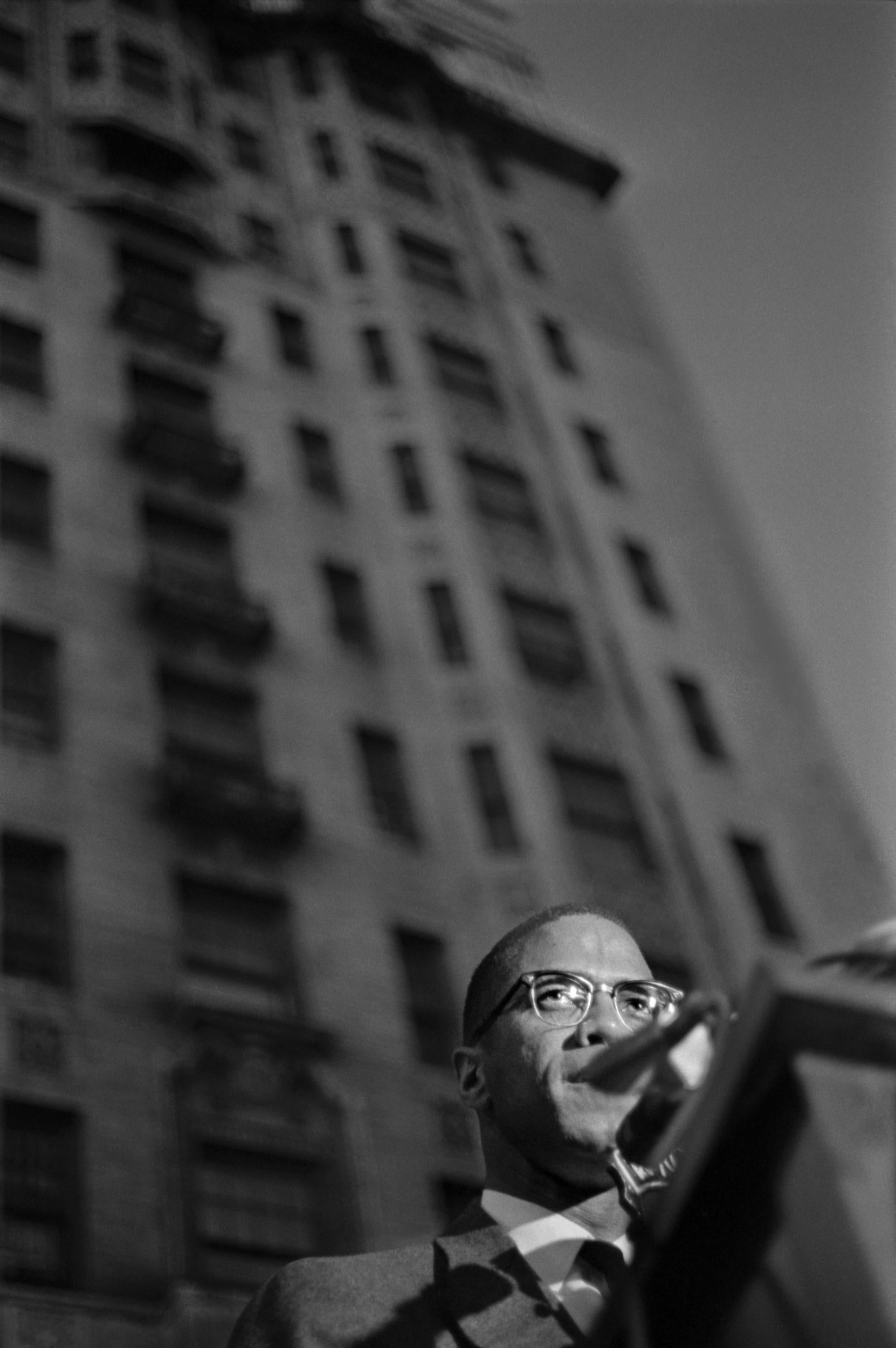

When asked about how much he thought about his role as a white man photographing black protests, he says his belief in the movement meant he didn’t feel like an outsider. “We were all in this together,” he says. However, not everyone around him felt the same. Two weeks after Malcolm X had given his famous 1964 speech The Ballot or the Bullet, Fink attended another of his speeches in New York. “A young woman got up and said, ‘You just gave that speech The Ballot or the Bullet.’ And she pointed at me. She said, ‘I have a bullet for that man back there!’” As Fink recalls, Malcolm X intervened. “He said to her, ’Sit down sister! That man’s going to vote with you.’”

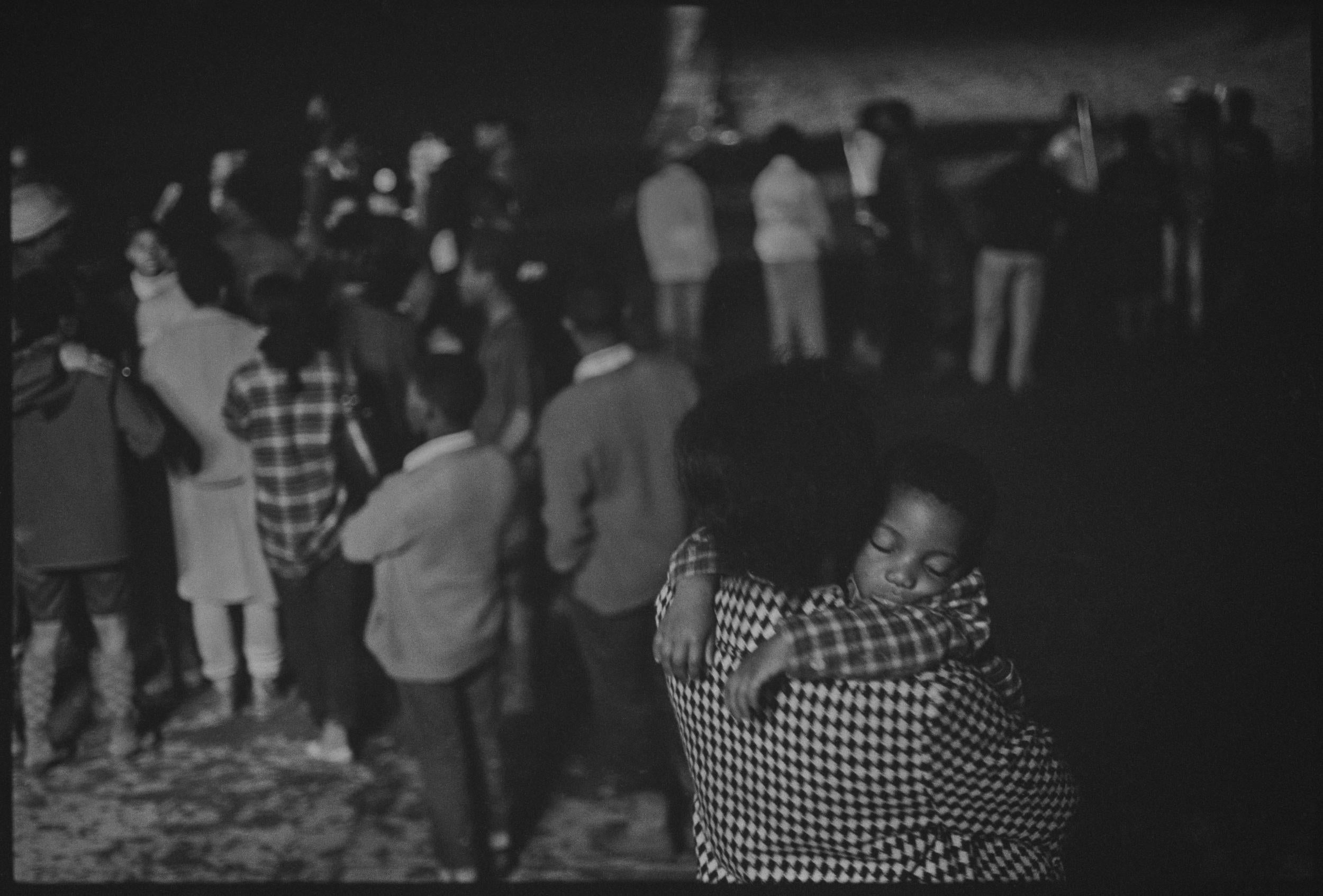

Despite being a Marxist, there was nothing dogmatic about Fink’s work. “I’m a human person, not just a political person,” he says. “I like people actually. Although I think they’re a pain in the ass!” Compassion is the main entry point from which he makes his work, which has largely focussed on gatherings and social situations. His best-known work, Social Graces, contrasted working class and elite parties during the 1970s. He later went on to photograph Oscar parties and other big events for Vanity Fair, which are collected in the book The Vanities: Hollywood Parties 2000–2009.

He says he felt like an infiltrator to this world of dazzling wealth, although he always saw the humanity in everyone. “Emotions are primary to all of us, and it’s that which allows us the empathy factor,” he says. “In my way of thinking that’s how I need to photograph, to go inside the other person somehow and find what it is about them which is also about me.”

“With digital today I don’t use flash. I use a tiny camera to get really, really close. Just be calm, you can get real close as long as you can allow the person you’re photographing dignity – people can feel when you’re against them.” Despite his left-wing credentials, he refuses to judge the very rich. “Even though I might be astounded by wealth, I’m not revolted by the people in it,” he says.

One person resists his empathic gaze. “I was photographing for Vanity Fair when Trump got inaugurated. They would have liked me to photograph his inaugural ball. And I refused. I didn’t want to photograph him. I didn’t want to give him my attention. I thought he was a horrible person, I’ll give him nothing. I don’t want to see that motherfucker!” Instead, he photographed the Women’s March the following day.

Due to the coronavirus, Fink isn’t taking photos much at the moment, using the time to archive his life’s work for the University of Arizona instead. Going back over his old prints, he has time to reflect even as he watches the protests carry on in the streets outside. “Every protest you think you get a roadmap, but then greed and capitalism and the Republicans and their white identity just keep on beating you back,” he says. “However, it’s the nature of human kind to keep on fighting. Even through bitterness. One does fight for hope, that’s all we live for basically.”

Larry Fink will release a charity print edition of his photograph ‘Many Shades of Concern’ via the David Hill Gallery with all proceeds going to the Until Freedom Organisation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks