Renaissance man

The work of London-based artist Raqib Shaw rewards at every level, says Tim Willis

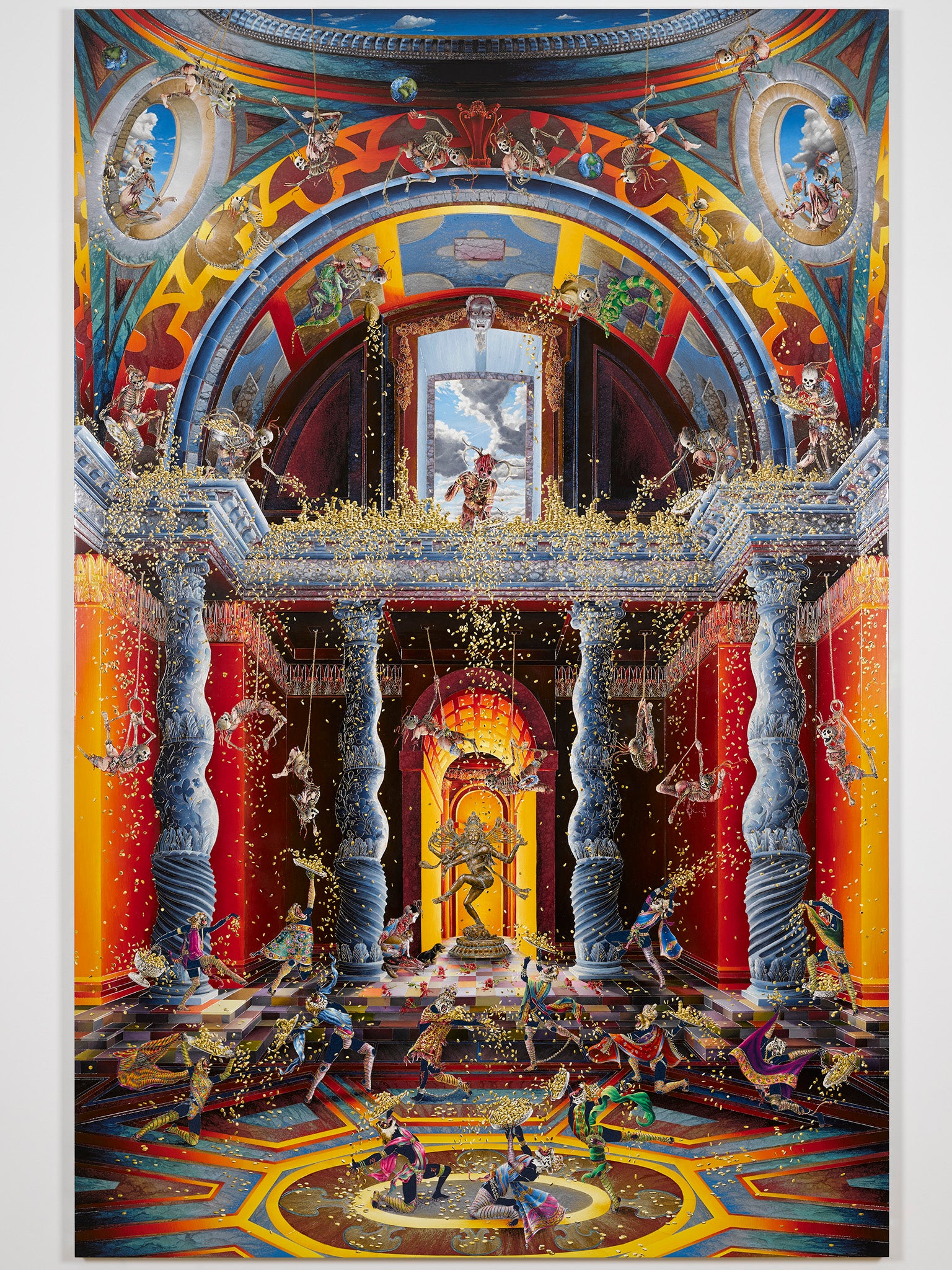

No reproduction could do justice to the work of Raqib Shaw, the Peckham-based Indian artist showing at the White Cube in Bermondsey in London from next week. If you can manage it, you really should get down to the gallery and behold his pictures – some are 20sq ft in size – in all their shimmering majesty. Technically clever, beautifully – sometimes intricately – executed, and all based on works in the National Gallery, they’re the Renaissance on acid. If you talked art-speak, you could even say they addressed contemporary issues around identity, exile, multiculturalism and the two-way dialogue at its heart.

A former St Martin's student – at a time when nobody hip was painting with any proficiency, and to do so was sneered at – Shaw takes the architecture from the cinquecento’s best-proportioned paintings and introduces into it his own subconscious. He replaces the figures with those from his imagination. The result: the eternal and actual, the known and unknown meet in a dazzling display.

Look at his take on Catena’s St Jerome in his Study, the centrepiece of this show. There’s a blue-skinned Krishna-self-portrait sitting in the place of the monk, with a Kashmiri lake and hill-village visible beyond. But now the spartan space is filled with fruit and flowers and carpets; the plain desk has become an elaborate lattice of bones; there’s a casket of skeletons, a sleeping leopard, some quails – and Shaw’s little dogs, one sitting on his lap.

Or look at the columns and arches borrowed from Venusti’s The Purification of the Temple. Instead of framing Christ and the money-changers, they are now like a Las Vegas show set, where Shiva and her creatures dance through the palette of a Grateful Dead album sleeve. Or the crumbling stable walls from Gossaert’s The Adoration of the Kings, transplanted to the Kashmiri mountain where Shaw grew up, with the artist centre-stage in a kimono, nursing his Jack Russell while hyena-headed Magi pay homage and green parakeets swoop overhead. They say that artists such as Tracey Emin are autobiographical. Compared with this guy, they’re drawing with crayons on mirrors.

Shaw, an immensely likeable recluse who surrounds himself with flowers, bonsai and bone china, says his work “goes from Hell to Paradise, and vice vesa” – which could describe his own journeys, interior and exterior. Raised in Kashmir before its religious and political troubles flared into today’s violence, he treasures and polishes his memories of a lost Shangri-La. Intended for a job in trade with one of the family firms, when business took him to London, he veered off his career path and was banished from hearth and home with £800 in his account.

A talented drawer, Shaw charmed his way into college at 19 and learned from the best: Breughel, Mocetto, Cartena

That’s because it takes about a day to paint four square inches with Shaw’s special concoction of oil-paint and Hammerite (which dries to a hard sheen). Using ancient enamelling techniques, he frames each tiny block of canvas – some no bigger than a darning needle’s eye – with slivers of glass, creating little enclosures into which the colour can flow from his ultra-fine, badger-hair brushes. As the paint dries, it takes on a “fired” aspect.

It’s a huge effort and Shaw says he’s thinking of downscaling, retreating to his tower and painting little masterpieces in exquisite isolation; maybe even moving on from this Renaissance-proportion thing. If I was a billionaire, I’d snap up these big ones while they last.

‘Self Portraits’ by Raqib Shaw is at the White Cube, 144-152 Bermondsey St, London SE1 from 13 July to 11 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks