Tatum O'Neal on her new podcast, being a child star and her recovery from drug addiction

Daughter of Ryan O'Neal and former wife of John McEnroe, Tatum O'Neal won an Oscar aged 10 for her role in ‘Paper Moon’, but later became addicted to heroin. At 54, she's telling her painful story in a podcast, ‘Tatum, Verbatim’

The actress Tatum O’Neal is taping her new podcast, Tatum, Verbatim, at a studio and arguing with her producer, Brian Howie.

Howie wants O’Neal to project the logo of her podcast – a black-and-white photo of herself with the words Tatum, Verbatim imposed over it – on a large flat-screen television sandwiched between black leather sofas where she and her daughter Emily are sitting.

“Why would I want a big picture of myself next to me?” O’Neal says.

Howie presses on, as producers are apt to do. “You should want a picture of yourself there,” he tells her. “I have a picture of my logo flashing next to me during my podcast,” he insists.

“No,” she says. “It’s tacky.”

At 54, O’Neal is used to putting her foot down, she says later that day over lunch at Spago. “My entire life, I’ve been saying no to everything. No, no, no,” she said. “I want to be a yes person.”

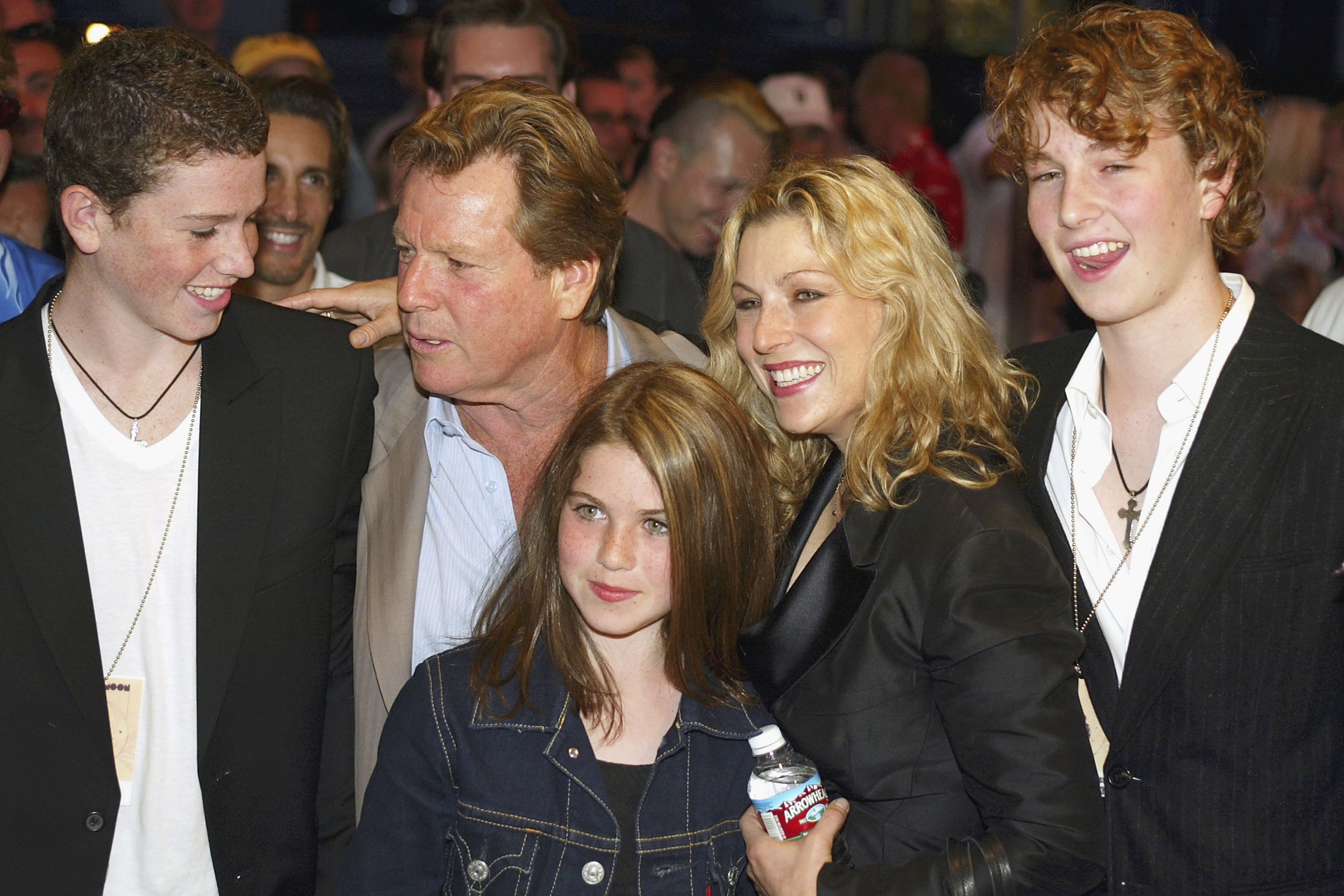

O’Neal was born to actors Joanna Moore and Ryan O’Neal, who split up when she was four. In 1974, at 10, she was the youngest person to win an Oscar, for her role in Paper Moon, a movie she stole from her co-star father. Soon she became his accessory in Hollywood, befriending adults like Cher, Bianca Jagger and Anjelica Huston. When O’Neal was 16, her father left her in charge of her younger brother at their home in Malibu when he moved in with Farrah Fawcett in Bel Air, as she wrote about in her 2004 book A Paper Life.

In 1986, when she was 21, she married tennis star John McEnroe, then at the height of his career. They had three children and six years later they separated, with People magazine screaming: “End of the Love Match.” Their relationship was immortalised in an Andy Warhol painting, which sold in 2008 for more than $300,000.

After her children were born, O’Neal became addicted to heroin. She spent years trying to get clean. She had her children taken from her. She had a public relapse and arrest in 2008. In 2011, she tried unsuccessfully to reconcile with her estranged father through a reality show called Ryan and Tatum: The O’Neals, which aired on OWN.

Years after the youthful success she enjoyed in movies including The Bad News Bears and Little Darlings, there were also new acting roles: as Denis Leary’s belligerent, alcoholic sister Maggie Gavin on Rescue Me; as a vacant trophy wife in Basquiat; and as Kyra the shoe shamer on Sex in the City. Last month, she filmed God’s Not Dead: A Light in the Darkness with John Corbett in Arkansas.

A friend set O’Neal up with a manager recently. They were at a breakfast meeting, discussing how well O’Neal was doing. Things are good, they’ve been good for a long time, O’Neal said.

“But your arrest,” the manager said.

Some have observed that it is harder for female stars in Hollywood to come back from scandals than it is for male stars, like Mel Gibson; it was 15 years between Winona Ryder shoplifting in 2001, for example, and Stranger Things.

“Its easy to become embittered,” O’Neal says. “It’s easy to cover up the embitterment with a ton of alcohol and a ton of drugs. But I choose to do what I feel comfortable with. And for me, I know what I’m the best at. And it’s acting. So I’m going to keep trying to do that even if it’s way harder for me than it is for a guy in the same position.”

O’Neal, for the record, wasn’t dying to say “yes” to a podcast. She barely knew what a podcast was. But it’s a growth industry, with 46 million monthly podcast listeners in 2015 expanding to 67 million this year, according to Edison Research, a data company.

Women host only about 10 of the top 100 podcasts on iTunes (one is Oprah’s Super Soul Conversations, which isn’t new material), but their voices are growing. In 2015, Werk It, a women’s podcast festival began. There’s 2 Dope Queens, Anna Faris Is Unqualified, Invisibilia and Another Round.

Sheri Salata, who was co-president of OWN until 2016 and who is now a host of a podcast, This Is Fifty With Sheri and Nancy, believes O’Neal is a modern-day truth-teller.

“She has nothing to hide,” Salata says. “She doesn’t have to put pink paint on anything because throughout her life, when she had the opportunity to tell her story, she’s been incredibly honest.”

O’Neal’s son Kevin McEnroe, an author, said that people had approached them to do reality shows for years, which he felt was the worst possible thing to do.

“You’ll just end up with an edited version of yourself versus what she has, which is that kind of natural charisma. And she’s funny,” Kevin McEnroe says. “With this new medium, you can see what it’s done for people in recovery like Marc Maron. You can speak openly about things, when maybe you didn’t have a chance to otherwise.”

O’Neal can’t not speak openly, but she is concerned about sounding too self-involved. She doesn’t want to talk just about old Hollywood. She wants the podcast to reflect her curiosity about life in the present. “When you stop being curious, you’re in trouble,” she says. She doesn’t want to merely rehash her stories, either: she wants to explore other people’s stories. Which is why she brought her daughter in.

Emily McEnroe, 26, has a deep, gravelly voice – a combination of her father’s Queens-influenced stony delivery and her mother’s rasp – and is a fitting sidekick. She talks about being harassed as a door girl at a bar in Los Angeles. (A guy grabbed her recently and said, “Time to go to the strip club!”) She discusses her voiceover and acting auditions.

In the first few episodes, O’Neal and her daughter tackled heavy topics: What is it like to have famous parents? What was it like to have a mother who is a drug addict?

O’Neal has done rehab and 12-step programmes, though not currently. “In this town, if you’re not in the programme, people think you must be out on the street with a needle hanging out of your arm,” she says. “I think that’s a fallacy.”

McEnroe has tried EMDR (eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing, which encourages the person to briefly focus on the traumatic memory) and other “trauma work”. She also dabbles in alternative practices, most recently baking in a 150-degree infrared sauna. “It was awful,” she says.

On and off the air, O’Neal is noticeably sensitive to the wounds inflicted by addiction.

“We’d talk about it, and I would be triggered by something,” McEnroe says. “My mum would check in with me. ‘Are you OK with this? Is it bringing up feelings for you?’ Because for a long time, I got inward as a teen and stopped talking. [But] I really want to have this conversation brought up more and not be taboo and not be strange. I don’t think it’s something that should be filled with shame.”

O’Neal would like to host John Frusciante, the musician and former member of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, who also had a very public battle with heroin addiction. She is working on her interviewing skills. “I don’t necessarily listen as well as I’d like to listen,” she says. “But I’m learning to do that.”

For a recent episode, she spoke with Jennifer Sklias-Gahan, an actress who is married to Dave Gahan, the lead singer of Depeche Mode. The two women met in Manhattan in the 1990s.

“She’s been through it,” Sklias-Gahan says of O’Neal. “But she’s very intuitive and insightful and still vulnerable, which is almost impossible to keep that with the world that she’s navigated. And going through some of the things that she’s gone through. I know how hard it is as a woman.”

During the podcast taping that day, O’Neal talks about how her father dropped her off to stay with Stanley Kubrick’s family for a year while he was making Barry Lyndon. (“So a play date forever,” McEnroe deadpans.) O’Neal and Vivian Kubrick (Stanley Kubrick’s daughter) were nine and 12. One night the two girls were playing in the bathtub, and Vivian Kubrick cut O’Neal’s hair off. It’s why O’Neal wore that on-trend pixie cut to the Oscars.

There was the time she was staying at the Stanhope Hotel when she was 20 and someone broke into her room and scrawled on the wall, in her red lipstick, “Who do you think you are, Shirley Temple?” A profanity was added for good measure.

At lunch, there are more stories. The time she was in her early teens and she and Melanie Griffith, also in her teens, went to Roman Polanski’s apartment in Paris and he showed them the X-rated, sexually violent Japanese film Realm of the Senses, an experience O’Neal describes in her book. “He didn’t touch me or do anything at all, but that was a lot to see,” at that age, O’Neal says. “I shouldn’t have been there.”

O’Neal also says she lost her virginity at 14, on the set of International Velvet in 1977 to a member of the crew who was in his thirties.

Though O’Neal wrote about the experience in A Paper Life, she did not mention the crew member by name, and struggled with this decision. Years later, it remains painful. Like many victims, she blamed herself. She says she put on tight pants to seduce him. In old footage of International Velvet, O’Neal was a beautiful, fresh-faced teenager, but she was scrawny, just starting puberty. She hadn’t yet gotten her period. “I didn’t understand the difference in our ages,” she says. “I thought something along the lines of, ‘This is what people do.’”

This was part of the damage of being a child star, one with little parental supervision, she says. O’Neal says that a few years later she ran into the crew member and it was shameful and embarrassing for her.

Many therapists will tell you that you have to go backward to go forward. At the opening of her podcast, O’Neal declares, “I was going to start with something super-highfalutin’,” then adds as an afterthought, “I’m bumbling my way towards enlightenment.”

Her daughter quizzes her a little about this and O’Neal explains that for her it was about distancing herself from her past so that she didn’t always live in the pain of what happened to her. That she wanted to find a sense of empathy for the people who have hurt her. She wants to release all of the damage that happened in her life.

“I’m nowhere near any kind of enlightenment,” O’Neal says, in her typical self-depreciating delivery. “So I just want to preface that.”

But McEnroe disagrees. “I think you are,” she says.

“You do?” O’Neal says, her voice rising an octave.

“Yeah,” McEnroe says. “You’re on the road. That’s all you can be.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks