Grief Is the Thing with Feathers: ‘Max Porter’s Crow is a nightmare entity everyone in mourning will meet’

As Cillian Murphy stars in Enda Walsh's stage adaptation of the novel by Max Porter, Douglas Greenwood reflects on how, since his own mother's death, grief and imagination have always been intrinsically tied

I still remember a bout of sickness I had shortly after my mother’s death 16 years ago. Aged eight, I was lying in bed, staring at the walls of my bedroom and imagining things that weren’t there: kitchen cupboards; floating footballs; birds. One part of me thinks it was a disorienting fever dream, but another, one that gets more convincing the more I dwell on it, thinks it stemmed from somewhere deeper and psychological. Following the sudden departure of my childhood matriarch, my mind was starting to play tricks on me.

Untethered imagination and finding solace in the impossible when death affects you is something that strikes through the heart of Max Porter’s Grief Is the Thing with Feathers too. It’s a novel that, when it was released in 2015, was praised by the British literary press for its striking treatment of death and the unconventional structure of its prose. Described by its publisher Faber & Faber as “part novella, part polyphonic fable, part essay on grief”, it uses three interwoven narratives told from different perspectives – those of a father, his sons and a crow that arrives at their front door in the dead of night – to guide its characters from a moment of deep mourning into a more hopeful future. When I first read it, belatedly and at the urging of one of those crass “Amazon Recommends” lists, I felt like something had changed. The experiences I once considered unique, I suddenly realised, were shared. Not only because this narrative mirrored my own almost perfectly (I have a sister as well as an older brother), but because I know what it feels like to trust in something intangible, and believe that vivid imagination, or escapism, can pull you through.

Grief and imagination have always been intrinsically tied for me. Throughout my mother’s battle with breast cancer and in the year or two that followed it, I was a fantasist. I dreamed of a life that wasn’t my own for a while, talked to myself about what it would be like to be famous, and found myself confiding in things that didn’t exist – like a Crow – purely to have someone to talk to. You see, when someone within your immediate family unit passes away prematurely, the idea that everybody gathers round to share their memories and express how much they miss them is farcical. Unless you’ve been brought up in a flawless setting, chances are those first few weeks and months are going to be shaped by pain and conversations no one instigates. You cry in private more than you do with those you love, out of embarrassment and self-pity. A mention of the missing piece’s name is enough to have every ounce of happiness in a room rush out of the door. Your mind might be tricked into thinking that the person didn’t even exist in the first place.

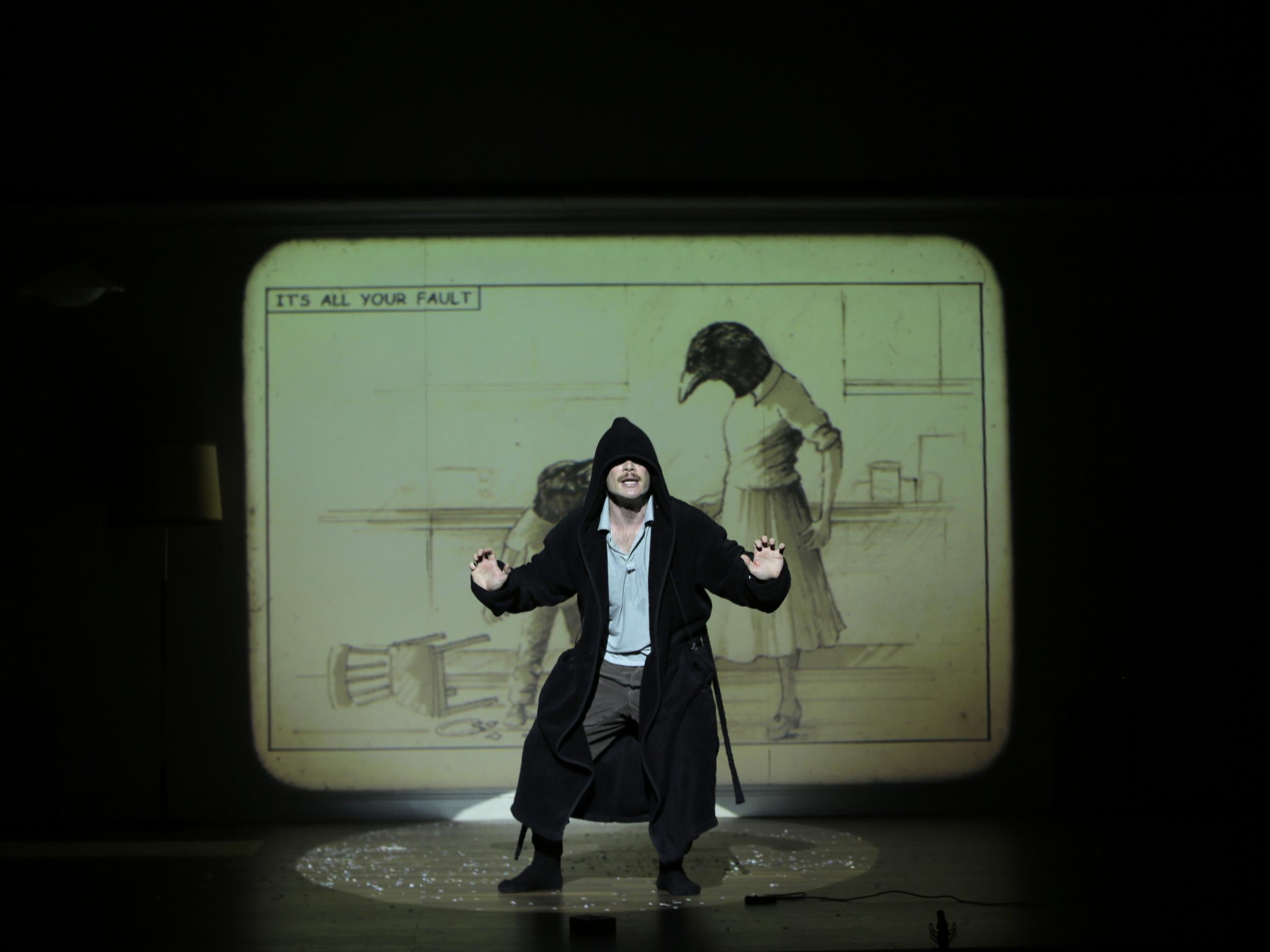

The same is true of the characters of Max Porter’s novel, which has been adapted for the stage by the Tony and Bafta-nominated writer and director Enda Walsh, and is playing a short sold-out run at the Barbican – with an immaculate Cillian Murphy assuming the role of both Dad and Crow. As Murphy flits brilliantly between the two, the only thing that ties Dad to his sons during the period of mourning is grief itself: inexplicable and strange, hard to decipher and difficult to discuss; the proverbial elephant in the room. The aforementioned Crow appears to represent their struggle: a cacophonous and confusing entity that has the ability to trick them (like when he promises to bring the boys’ drawings and sculptures of their mother to life, despite knowing it isn’t possible), and hurt them. He’s an abrasive figure – wise and cunning, his dialogue peppered with gobbledygook rhymes and avian “kaaaks!” – but he also harbours the ability to deliver hard truths, and say the things that others won’t. Whether or not Porter’s Crow is real or merely a metaphor doesn’t matter to me, because he’s an entity everyone in mourning will meet: a nightmare that, by existing, affirms all nightmares come to an end.

It’s funny how the most piercing interpretations of grief manifest in brief formats. What I felt throughout Max Porter’s 114-page book and Walsh’s sub-90-minute interpretation of it on stage, I also felt in Michel Faber’s sorely underrated collection of poetry dedicated to his recently passed wife, Undying: A Love Story. While long-form narratives offer the opportunity to dig beneath the surface of someone’s psyche in moments we process death, what Faber, Walsh and Porter’s decided structures do is offer up the kind of immediate analysis that’s more truthful, and dizzying on impact, like death itself. There’s a poem in Faber’s book titled “Risotto”, in which he deftly explains the experience of reheating frozen leftovers for dinner; ones his wife made him that have sat dormant and waiting since before she passed. It’s that dissection of the morsels of beauty we find in deep grief that makes the format of that poem’s delivery so profound. By the time you reach the final stanza of the collection – something you can and should consume in one sitting – the potency of Faber’s words rid you of your appetite, as if you’ve just been delivered a heady dose of bad news. Once it’s over, pent-up tears are released with the impact of a bursting balloon. And it feels glorious.

For the longest time, grief has been a hard thing to interpret through art because it’s often used in an opportunistic way; the subject of “tearjerkers” that wind up clunky and cloying when executed. I’ve watched countless fathers, mothers and sisters die in films or in books, but few have moved me, because the experience is so impossible to pin down. What makes Grief is the Thing with Feathers work so well is the way Porter’s words dance between despondency and hope, and how, on stage, Cillian Murphy puts himself through both sides of the experience – both as grief and its victim – to gain a greater understanding of it. The same words that struck me on paper rang in my ears when Murphy spoke them. In the final moments of Porter’s story, the Crow describes the boys, now departing the grieving process, as “connoisseurs ... in how to miss a mother”. Sixteen years later, I recognise that.

I realise now that there are two things that make me cry over the death of my mother: one is standing at her grave and the other engaging with art that ruminates on pain through other people. I wept at Michel Faber’s stanzas about reheated risotto just as much as I did at the crushing first act of Matthew Lopez’s drama about queer lives past and present, The Inheritance. I shed a solemn tear at Laurie Kynaston and John Light’s gutting performances as confused father and depressed child in Florian Zeller’s The Son at London’s Kiln Theatre, just as I did the final page of Max Porter’s seminal book. Where conversations between relatives cease to exist out of awkwardness or a preference to forget, art and imagination always does.

I remember how I, like the boys of Grief Is the Thing with Feathers, once felt lost and angry after the death of my mother, but then I remember that grief is beautiful and wretched and painful, but, most importantly, necessary. And without it, we would yearn for an impossible return so strongly that we’d never learn how to move forward. That is perhaps the most common misconception about losing someone you love unexpectedly; one that the characters of Max Porter’s brave novel will encounter by the time they reach those bright white, blank pages that run on after the final words were written.

You can love someone immensely but not miss them once they’re gone. We miss buses. We miss friends we fail to make plans with, but think about that emptiness that comes with “missing” someone or something, and you’ll seldom attest to feeling it all of the time or years after the person left you. What they provided for us when they were alive is outsourced to the still living. Instead, it’s the love they gave that defines us.

That itself is a product of bereavement, and it soaks the pages and the stages that Grief Is the Thing with Feathers occupies: that we go through it not to miss, or feel pain, but to block out bad memories in favour of the good. For anyone, like me, who’s had to say goodbye to someone too soon, Max Porter’s story of a family in mourning finding light is like a look back on photo albums or family videos, only in strange and somewhat blissful fictional form.

Grief is the Thing with Feathers is showing at the London Barbican until Saturday 13 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks