From Harold Pinter’s Betrayal to Christopher Nolan’s Memento: why create art that goes backwards?

As ‘Betrayal’ returns to the stage, starring Tom Hiddleston, Paul Taylor looks at the vast body of art in which people are shown living their lives backwards – to arresting and revealing effect

Life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards”: Kierkegaard’s statement – shaped in just the right reverse sequence – has the undeniable ring of a profound truism. But it needs to be tweaked for 21st century consumption. For, by now, a surprisingly large and diverse body of art has amassed in which people are shown living their lives backwards – to arresting and revealing effect. Harold Pinter’s Betrayal (1978) is, by general consent, the pre-eminent play in this category. A revival just opened is directed by Jamie Lloyd and starring Tom Hiddleston, who is principally famous for TV’s The Night Manager and for portraying Loki on the big screen.

It’s the actor’s first stage appearance since he played Hamlet for Kenneth Branagh in a fundraising production for the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. The drama school’s theatre has a capacity of 160 seats. The run was three weeks. The tickets had to be issued by ballot. If appreciative punters fell on the production like fiends, it was a very select minority. By comparison, this revival of Betrayal is, as they say, anybody’s. Well, up to a point. The production is at the Harold Pinter Theatre, capacity 796. There are 26 performances. So go figure. All the same, this is bound to be the hottest of tickets.

The cast for the three-hander also boasts Charlie Cox and Zawe Ashton. And the production is the coda to the remarkable six-month Pinter season by Lloyd. It has had succulent casts throughout and a blessed lack of acolyte preciousness. I’ve been at Pinter first nights at some other theatres where the hushed reverence of the faithful has left me near-comatose with nerves lest my interpretive faculties failed me. Lloyd deserves great credit; his season will have won Pinter a lot of young admirers; what you lose in terms of the nosebleed exclusivity of the Rada Hamlet, you gain in the irresistible combination of a rough-and-ready vibe in the auditorium and fierce finesse onstage.

Hiddleston plays Robert, a publisher and the best friend of literary agent Jerry with whom he has close professional ties. The pair are close in other, less recognised, ways too. For seven of the play’s nine scenes, Jerry is having an adulterous affair with Robert’s wife, Emma. The affair runs its course in reverse chronological order. The first scene is set in 1977, two years after the affair ended, in a pub where the former lovers are having their first meet-up alone since the split. It ends in 1968 with Jerry’s (possibly) drunken, flamboyant declaration of love for her. The setting is her shadowy, lamp-lit bedroom where he has been lying in wait for her. Robert, her spouse, sizes up the situation when he wanders in. But instead of expressing anger, he seems to accept Jerry’s florid assurance: “I speak as your oldest friend. Your best man.”

Pinter, who based the piece on his own affair with Joan Bakewell, the author and broadcaster, said that “when I realised the implications of the play I knew there was only one way to go and that was backwards”. By reversing the chronology, virtually everything is seen in the shadow of disillusion and treachery is foretold. Pinter sensitises us to the labyrinthine, corrosive nature of betrayal. Our vastly superior knowledge may occasionally make us laugh at the characters. But you’d want to seek psychiatric help for anyone who gurgled with mirth throughout. Just as you would for anyone who kept up a steady stream of tears at the play’s silting accumulation of pain.

A backwards structure in drama is sometimes used to chart a regression/progression from cynical disenchantment to original innocence. Pinter’s material has a heightened homing instinct for the start. It wants to show us that there’s no unambiguous moment of pure irreproachability. It shifts our concentration from the normal lockstep of cause and effect so that we can muse on our changing perceptions of which, from the gradually gathering heap of betrayals, is the most grievous. Is it the fact that Robert fails to tell Jerry that he has found out about the affair? Or is it his inscrutable sanctioning of it (perhaps) in the first scene? Robert and Jerry are homosocial rather than gay, but there are undercurrents.

In 1970, Pinter had directed a fine National Theatre production of Exiles (1919), James Joyce’s play about a tortuous love triangle in which there are heavy hints that the female character has drawn the short straw of being the surrogate through which the two men explore their growing mutual attraction. It’s doubtful that Betrayal would have taken the form it does if Pinter had not directed Joyce’s wildly ahead-of-its-time play first.

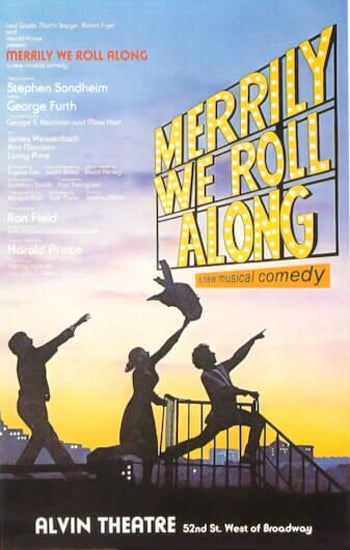

Sondheim’s 1981 show Merrily We Roll Along occupies the equivalent place of honour amongst musicals for the brilliance with which it marries retroverted form and content. Peeling back strips of time layer by layer, the piece takes three friends – a composer, a lyricist, and a magazine writer – from embitterment and compromise in 1976 back to the tingling hope of youth in 1957 when the world lay all before them and they gathered on a New York rooftop to watch Sputnik. A run-of-the-mill composer might have registered the passage of time through changing fashions in music. Instead, Sondheim unforgettably communicates it by reversing the principles of reprise and quotation that are conventional in musical scores.

In Merrily, we first hear a snatch of the composer’s hit song “Good Thing Going” sung by Frank Sinatra on the radio. In the reverse chronology of the show, it’s been established as a standard long before we watch the struggle to pen it. “And while it’s going along/ You take for granted some love/ Will wear away/ We took for granted a lot/ But still I say/It could have kept on growing/ Instead of just kept on/ We had a good thing going/ Going/ Gone”. It’s quite rolling-hipped in its melancholy beauty when we first encounter it in the piece; then the tone and tune of the first line (“It started out like a song”) are progressively pared down to the hectoring stab of one finger at the rehearsal piano as the young hopefuls try to conjure up the hit that will justify the hope. As emotionally stirring as it is ingenious.

Could you identify the author’s gender from one of these counter-clockwork exercises? I thought it unlikely. Now I am not so sure. There’s a quote from Woody Allen, “In my next life I want to live my life backwards,” that looks forward to nine months of luxurious spa-like conditions: “And then voila! You finish off as an orgasm.” A bit self-aggrandising. I thought you were the result of one (possibly two). By contrast, I can’t readily picture a man writing these lines from Alice Oswald’s remarkable poem “The mud-spattered recollections of a woman who lived her life backwards”. She writes of the terrible morning “they came to insert my third child back inside me”. So far, so graphic. Then the devastating poignancy as the mud-spattered woman recognises the emotional implications: “I leaned and cried/ and a feeling fell on me with a dull clang/ that I’d never see my darling daughter again.” A step up, artistically, from imagining yourself as an orgasm.

It’s sometimes hard to get your head round the philosophical ramifications of life lived backwards. How much memory are you allowed of the future you have already experienced as you march forward into your ineffable past. Christopher Nolan’s Memento – the most brilliant and endlessly suggestive of the movies on the subject – incorporates this problem and makes it essential to the logic of the story. The film alternates between a black and white strand that proceeds chronologically and one in colour whose reverse sequence (one step forward, two steps back) is designed to give you a taste of the perplexity experienced by the protagonist. Leonard was an insurance man whose job was to uncover fraud. Now he is suffering from chronic short-term memory loss as a result of a blow to the head from the thugs who raped and killed his wife. His obsessive mission to run them down is hampered by his condition; to keep track of what has just happened, he has to resort to taking Polaroid photos and preserving information in indelible tattoos on his body. The structure allows us to see twice and to reassess sequences that leave him bewildered about who to trust. And the suspicion stirs that, while Leonard’s condition is not fictive, it might be a massive insurance policy for keeping the truth at bay. It’s not fanciful to see affinities with Oedipus Rex. Insurance policies tend to backfire in most drama, but in backwards-moving plays particularly. We have seen the future and it does not work.

Memento finds an arresting metaphor for the worrying evaporation of memories in Polaroid photos. If footage of them is played in rewind, it looks as if the wet, developing image is drying off to a sublimated blank. Nabokov wrote that “Nobody can imagine in physical terms the act of reversing the order of time. Time is not reversible.” Maybe not, but it has not stopped people trying nor communicating why they feel such a pressure to do so. Including one of Nabokov’s greatest admirers, Martin Amis, who in his 1991 novel Time’s Arrow, presses the rewind button on the Holocaust. Except that that makes it seem facile whereas prodigious technical powers have gone into the book. It’s a knowingly grotesque irony that German guards and doctors become, in his reverse-Auschwitz, not just the saviours of the Jews, but their visionary begetters, drawing them down into being from the smoke of their extermination and pounding the gold teeth back into their gums. A sickening exercise in misplaced faux-sublimity? No, because the author’s tone is unbelievably supple, his savage indignation all the more lethal for being so sly, straight-faced, Swiftian. “Entirely intelligibly, though, to prevent lethal suffering, the dental work was usually completed while the patients were not yet alive.”

To my ear, this category of writing has produced some really impressive feats. Harold Pinter gave his friend, Samuel Beckett, Betrayal to read (a copy was by the bed where he died). This is what he wrote about it: “That last first look in the shadows after all those in the light to come wrings the heart.” In its tender plaiting together of prospect and retrospect, it does the play deep honour and is a little work of art in its own right.

Betrayal is at the Harold Pinter Theatre until 1 June (0844 871 7622)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks