Hugh Bonneville: ‘People say actors have no right to voice opinions. I’m a flipping voter, too’

The star of ‘Downton Abbey’ and ‘W1A’ speaks to James Rampton about the upcoming ‘Downton Abbey’ film, the revival of ‘Shadowlands’ and why Britain now is like Russia before the revolution

Hugh Bonneville is perched on a small chair eating a prawn salad in the Sunday school room at the American Church in central London. In these perhaps unlikely surroundings, he launches into a defence of the right of creative people to speak out about social issues. “People in the entertainment industry aren’t allowed a voice,” he contends.

“If you say anything, it’s, ‘Shut up, you have got no right to say anything because you act in plays.’ Well, I’m also a flipping voter! If I feel passionate about something, I don’t see why I shouldn’t be allowed to express it. I’m no less qualified than the next ranter, although I don’t rant.”

Passion might seem unlikely for the 55-year-old best known for playing such archetypally English, buttoned-up characters as Lord Grantham in Downton Abbey, Ian Fletcher in W1A and Mr Brown in Paddington. He is playing another emotionally closed-off character, CS Lewis, in William Nicholson’s acclaimed play Shadowlands, which opens at the Chichester Festival Theatre on 26 April.

But in real life, the garrulous, gregarious Bonneville displays no such diffidence, although he is aware of the dangers of speaking your mind. “If you do say something to a journalist, you can say 28 sentences, but only one sentence will be quoted and that will be the wrong one. So it’s easier to shut up and just do the gardening.”

I’m very glad to report that today he has no intention of just shutting up and doing the gardening.

He begins by tackling the subject of politics. “I’m not a political animal because I don’t have a consistent stance – I change my views about what works like I change my underpants. I’m not a supporter of the Tories, Labour or the Lib Dems and never have been, but there are elements of each philosophy which I completely respect.”

For all that, the actor is very concerned about what’s going on in our country. Bonneville, who has been married to Lulu Williams for more than 20 years and has a teenage son, is particularly exercised by the terrible mess the UK is in at the moment.

He often portrays a pillar of the establishment, but unlike many of his screen alter egos, Bonneville does not unquestioningly support the status quo. Dressed down in jeans for a Shadowlands rehearsal, he jokes that, “Luckily, in our country we have made such a fantastic success of our political structures recently.

“Oh God, the mess! Yes, we had some ups and downs in the past, but our parents’ post-war generation handed us a Britain that had a sense of identity, purpose and confidence. We could do things like trying get on the property ladder – good luck with that these days.”

Bonneville adds that, “Now I feel ashamed of what we are handing to our children’s generation – a broken political system and a national identity crisis. God knows where we’re going to be in five years’ time. Our civic voice is non-existent now, and that’s very depressing.”

The exasperation clear in his voice, he continues: “Our children’s generation need a new approach to politics. Perhaps you do that through proper grassroots town-hall politics that then cascade upwards.”

The actor also despairs of the way in which the tenor of political debate has become so toxic. “I have enormous respect for those who try to make a difference in our culture because it’s currently an extremely volatile arena, and a lot of scary abuse is flying around. If leaderships – and I don’t just mean British leaderships – only use ad hominem attacks on people to ram their point through, it sets a terrible example, whether that’s in America, Venezuela, Italy or anywhere else.

“If you tell an eight-year-old that he needs to behave properly, he will say, ‘Why should I? I saw that the president of the US called one of his colleagues a ‘thin-necked tw*t’ and I saw the leaders of congress holding up banners saying, ‘liar, liar, pants on fire’.’ It’s playground stuff.”

In September, we’ll see Bonneville in one of the most widely anticipated cultural events of the year: Downton Abbey the movie. He starts by addressing Downton creator Julian Fellowes’ mischievous recent suggestion that if he existed today, Bonneville’s character, Lord Grantham, would be a Brexiteer. “I can tell you, Lady Mary would have a few things to say about that! Let’s leave it at that.”

Bonneville goes on to reveal as much as he can about the plot of the new movie. “I get to move some chairs in the rain – spoiler alert! I trained long and hard for that.

“It’s fair to say that in the movie the world of Robert and Cora [the Earl and Countess of Grantham] is stable and that the energy and disruption of the story lies in other areas. If the movie works, let’s do another. It could run and run. After all, how many Star Trek movies are there?”

Does the elitism and the disconnect between the rich and the poor depicted in Downton Abbey at all reflect society today? Bonneville pauses. “As a construct, the idea of a feudal system is not a great one, is it?”

It’s true that one of the causes of the Russian Revolution is the fact that at the end of the 19th century aristocrats in that country often owned a million serfs each. “You could argue that we have got something similar to that now,” Bonneville carries on. “If you have got cash, you have got serfs, particularly if you’re a non-dom.”

(For the uninitiated, he’s referring to people who live in a country, but are not legally domiciled there, which often equates to not paying tax.)

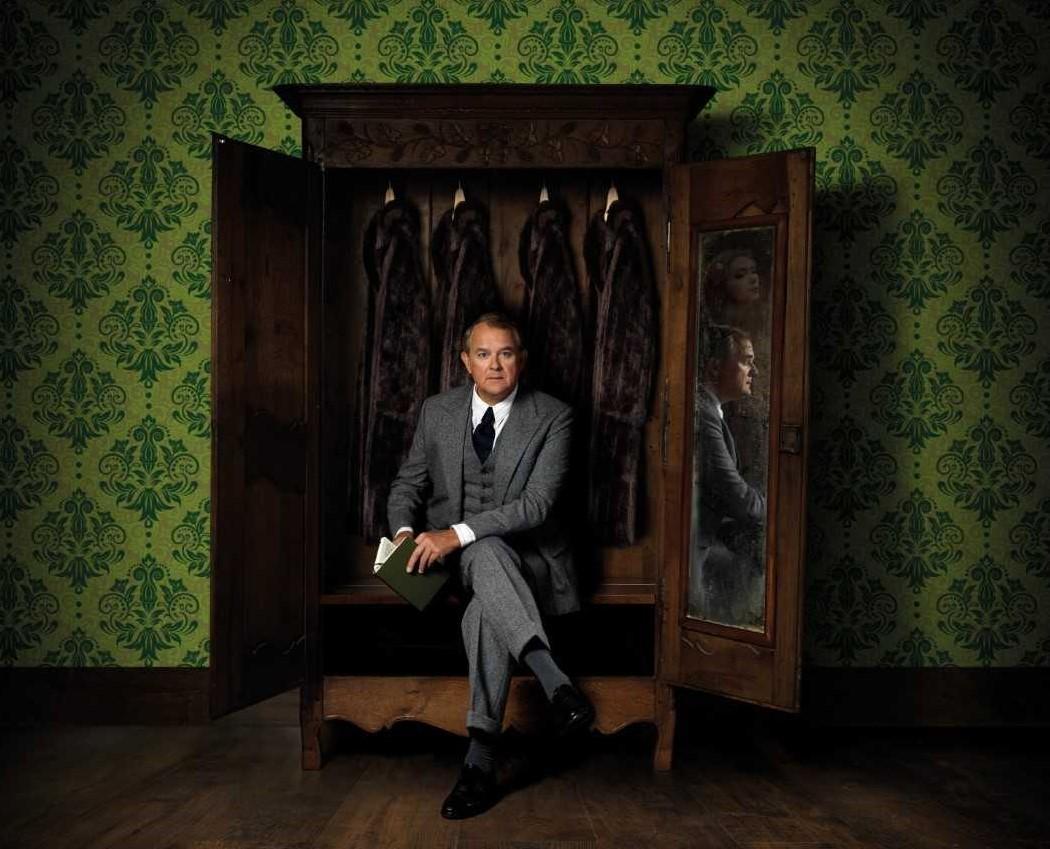

Shadowlands, meanwhile, which in previous incarnations has been a TV drama starring Joss Ackland, a West End and Broadway play with Nigel Hawthorne in the lead, and a movie featuring Anthony Hopkins, opens by portraying the author of The Chronicles of Narnia as a repressed, devout Christian who is happy only in the company of his fellow, male, cloistered Oxford dons.

His world is turned upside down, however, by the arrival of Joy Davidman Gresham (played in this production by Liz White, Ashes to Ashes), a vivacious and outspoken American woman.

At first, Lewis and Gresham spar and challenge each other’s philosophies, but love soon blossoms between them. When his now wife falls ill with cancer, his faith is sorely tested, and he begins fundamentally to question everything he previously believed in.

Bonneville thinks that, 34 years after its premiere, Shadowlands continues to strike such a chord because it illuminates a timeless theme. “Bill Nicholson told me that Joss Ackland had never had such a big mailbag in response to a show as when he starred in Shadowlands. That’s because this story is absolutely universal. Every single human being goes through loss at some point. This is about how you cope with it. It is a deeply affecting love story.”

After Gresham died, Bonneville continues, “Lewis wrote A Grief Observed, an incredibly powerful short book drawn from his own notebooks. He wrote completely spontaneously about what he was going through after Joy’s death. It’s very raw and human and calls his faith into question.

“In one striking passage, he talks about the selfishness of grief. Lewis realises that he is making it all about himself and not the person who has passed. But the book shows very well how grief ebbs and flows like waves on a beach, leaving different patterns in the sand. It’s a really interesting take on grief.”

Shadowlands also works, Bonneville argues, because, “It’s true. You could not imagine a more unlikely couple than Lewis and Joy. A dating app would never have put them together. In terms of romance, CS Lewis would be the last person you would choose. When they saw his profile, every woman would say, ‘I’ll swipe right, thanks.’ I don’t think Lewis would have been on Tinder. He wouldn’t even have had a phone. He’d have had a little Letts pocket diary with a pencil!”

Bonneville studied theology at Cambridge, and working on Shadowlands has afforded him the opportunity to become immersed once again in his old subject. Of his own faith, he comments that, “I went to Cambridge an atheist and came out an agnostic.”

All the same, he remains fascinated by religion. “I’m genuinely a respecter of all faiths. I just wish they didn’t create wars, but they do. That’s a big downside!”

Last year Bonneville reaffirmed his interest in the subject by travelling to Israel to make a documentary about the Passion of Christ, entitled Countdown to Calvary.

One image from the documentary lingers. “The most moving thing I remember was that at the bottom of the Western Wall in Jerusalem there were these enormous boulders. The Romans had pushed them off the top when they had destroyed the Christian Temple in AD70.

“They aimed literally to destroy a religion. They wanted to wipe it from the face of the earth. That brought home to me the pain that religion can cause and that we can cause each other.”

Bonneville goes on to consider the eternal conflict between different religions. “Will we ever find the path of tolerance that all religious scripts claim they hold? ‘My religion is more tolerant than yours, don’t you agree? Let’s fight about it.’”

The other major project on the horizon for Bonneville is Paddington 3. “I saw the Paddington producer David Heyman the other day, and he said, ‘We will only do the third movie if the script is as good as the first two. There is no point in doing it for its own sake.’ So with a fair wind, there could be another one before the children have beards!”

Before he has to go back to his Shadowlands rehearsal, Bonneville stops to ponder just why the first two Paddington movies have been such a success. “They struck a chord because they’re about kindness. They’re about people reaching out the hand of friendship when others need help.

“Ultimately, they’re about compassion and, goodness me, we could all do with a bit of that at that moment.”

Shadowlands runs at the Chichester Festival Theatre from 26 April to 26 May. Tickets are available on 01243 781312 or at cft.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks