Patrick Marber on 'The Red Lion', writer's block, and getting fired from 'Fifty Shades of Grey'

Patrick Marber tackles Turgenev and football in two new plays at the National. The Arsenal fan tells Alice Jones about his midlife crisis

"I wrote that play as a warning to myself – then ignored my own warning." Patrick Marber is talking about Howard Katz, a play he wrote in 2001 in which a 50-year old man has a midlife crisis. The playwright has now caught up to his character: he is 50 years old and, he says, "I did have a midlife crisis. I'm probably still having it. I did get lost and not know what I wanted and how to be in the world."

Marber's crisis manifested itself in a bad case of writer's block. A stellar career – highlights include The Day Today (he played Peter O'Hanraha-hanrahan and co-created Alan Partridge), the plays Closer and Dealer's Choice and an Oscar-nominated screenplay for Notes on a Scandal – looked to have burned out. His last play, Don Juan in Soho, premiered over eight years ago. After that came the "dead script" years, in which he wrote an adaptation of Don Juan in Soho for Film 4 and a screenplay of Ian McEwan's Saturday, among other films that never got made. "And then I didn't write a sausage for about four or five years. I was completely blocked." What did he do all day? "I have young children so I was doing a bit of hanging out with them… Sort of being a bit depressed. Just, you know, living." He says this last word with a weary horror.

"In 2012, I really thought, that's it. It's over. I've written what I can write." He started considering other careers and wondered if he might make a good sports journalist, writing match reports, interviewing footballers and so on. It was a woeful period. "It's not that there were no ideas, it's just that I didn't want to write them. It's an awful feeling, and I'm really scared I'll feel it again. It was awful, like depression but with lots of self-loathing as well," he winces out a smile. "Worse things have happened to many people but it was pretty bad."

Around the same time, Marber did what many middle-aged men in crisis might dream of doing: he bought a football club. He had moved from London to Sussex with his wife, the actress Debra Gillett, and their three young sons, a few years earlier and had become a regular at Lewes FC. When the club faced bankruptcy in 2009, Marber and a group of fellow fans cooked up a plan in the pub to save it. Pledging cash and selling shares for £1,000, they made Lewes into a community-owned club, like Barcelona. All football should be run by supporters, he thinks. "I never wanted to run a football club, I just wanted to carry on supporting it."

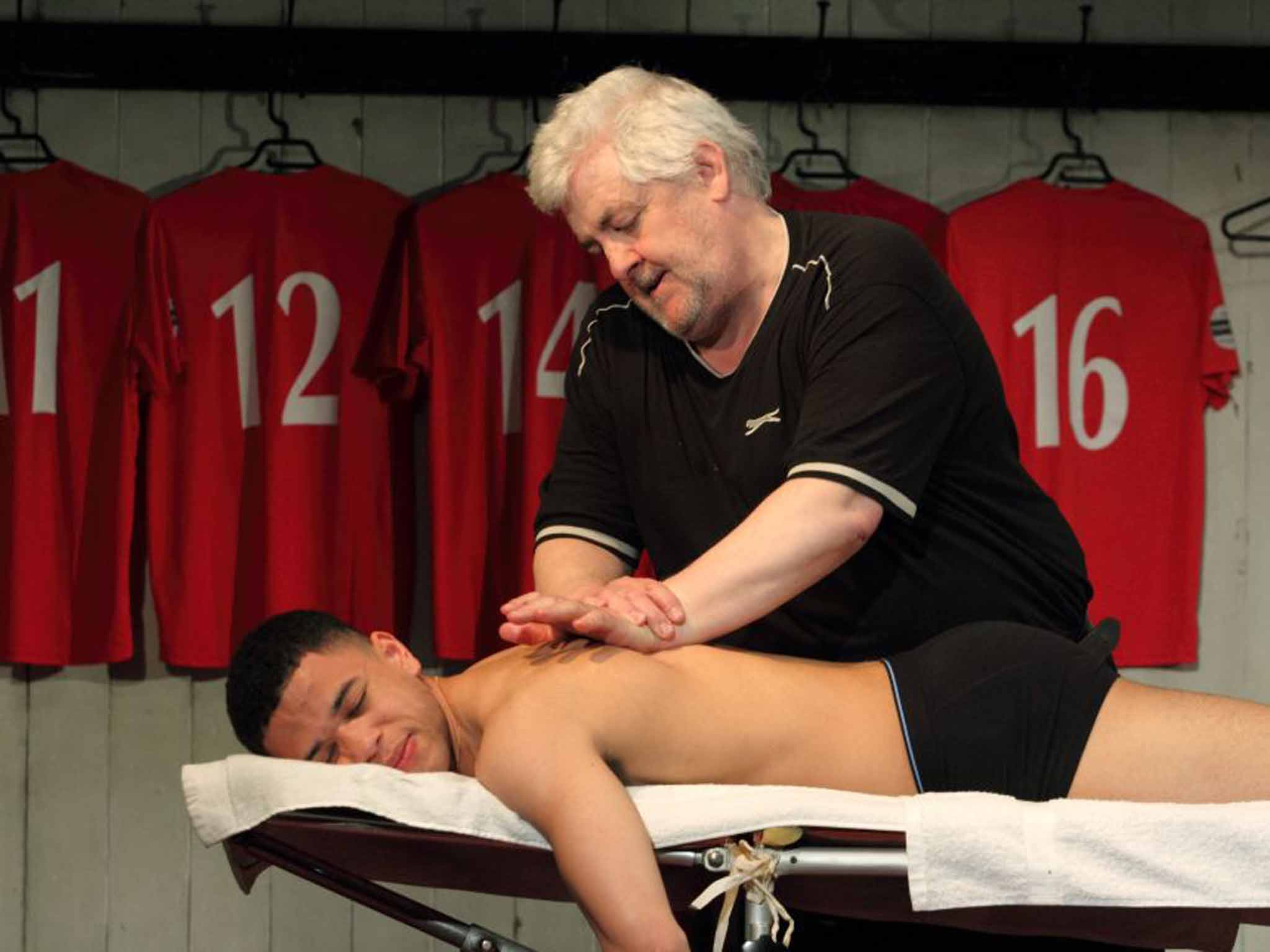

These days the club is thriving, but Marber is just "an interested fan", having moved back to London a couple of years ago. His own crisis shows every sign of being over, too. Today he is charming, calm and alarmingly articulate, blue eyes bright and hair bristling. We meet in the upper reaches of the National Theatre where he is preparing to stage not one but two plays this summer. Three Days in the Country is his "frisky" adaptation of Turgenev's 1855 play A Month in the Country, which he will also direct. The cast includes John Simm, Mark Gatiss and his own wife, in a part he wrote for her. The Red Lion is set – where else? – in the dressing room of a non-league football club.

The new play brings together the two loves of Marber's life: football (he is a lifelong Arsenal supporter) and theatre. "When I'm on a train and see an empty pitch, it gives me a certain pleasure that I can't quite describe. It's to do with potential..." Empty theatres provoke the same "romantic feeling" in him. That said, he never intended to write about Lewes and is keen to point out that the play is not really about football at all. It is about loyalty, belonging, and loneliness. "That always seems to be the condition of my plays..."

While The Red Lion is not really about football in the same way that Dealer's Choice was not really about poker, it is carved from the drama of Marber's life. Dealer's Choice was inspired by his youthful gambling addiction – at its height he was losing £10,000 a night and had to be bailed out by his father, a City analyst. Closer, he said, was born of "romantic stuff, a series of events in my personal life". It was only ever a matter of time before his Sussex years bore fruit. "My life is in dialogue with the plays that I write," he agrees. "The relationship I have with my plays is very, very intimate and I dot my life through them."

His return to writing was slow. He started talking to Ian Rickson about a new play in 2012. A year later he started handing in a few pages to the director every week, "like homework". When Rufus Norris took over at the National, he programmed it on the strength of the first act. Marber wrote the rest "in a kind of blaze".

He had rediscovered his mojo. And then he took a call from his old friend Sam Taylor-Johnson. They had worked together on a short film, Love You More, in 2007 (find it online, it is quite lovely) and stayed friends. She was in trouble and needed an urgent rewrite on the biggest movie of her career, Fifty Shades of Grey. Marber refused countless times until Taylor-Johnson persuaded him to read the book. Did he like it? "Sort of yes! Because I enjoyed reading something that a hundred million people have bought."

So it was that Marber found himself spending 10 "fervent" days in his office with Christian Grey. "At the time I'd done my back in, and was in quite considerable pain, in my own personal Red Room, bashing away at this thing… I was really happy being in that world." The producers were happy, too. "They said it was wonderful, you've saved our asses, you're a hero," he grins. "And then I was fired." EL James did not like what he had done to her book – he had "strayed quite radically", as per his brief – and he was booted off the project. "I felt a bit sad because I thought I'd written a good script. But I totally understood. If you take on a rewrite job – it's whore's money and don't expect them to love you for being a whore." He was "nicely" paid but still hasn't seen the film. "I think possibly I don't want to not like it," he says.

Now, still in recovery from the dreaded block, he writes every day – sometimes a scene, sometimes just a sentence. "Whereas before I had a bit of a neglectful attitude towards whatever talent I might possess, now I think, no, you have to try and nurture and water your tiny sprig of a plant." Moving back to his flat in Smithfield, east London, has helped. He couldn't write in the country. "I felt free in the fields and woods. But I missed the city with a passion. I realised that I need the randomness of the city – it excites me."

He writes in his office, which is the flat on the floor below his. It is studenty, filled with his old records and childhood bits and bobs, "reminders about things that make me feel". It's also where he keeps everything he has ever written, since he declared himself a writer, aged 14. "Occasionally I'll have a look at something I wrote when I was 15 and think, 'God, did I feel that?' It's the best account I have of myself." He writes best at night, settling in at 9pm and working through til 2am. "About 11pm is when I'm good. For the darker ink to come out – the things that I don't dare say in the day, that should be in a play, they come out at night."

Closer, his lacerating study of modern romance is still perhaps the finest example of this "darker ink". In fact, the play originally featured a third couple, he tells me, Jake and Natalie who were "quite happy, just bumbling along. Bit bored, not passionate, just fine". They were to provide a bit of light relief against all of the heartbreak and infidelity and fists wrapped in blood. "Once I eliminated them, I had the play. I had to recognise if I softened the play, I diminished the play."

Having premiered to critical swoons in 1997, Closer had its first major revival at the Donmar this year. "I thought all the things I like about it are still there and all the things I don't like about it are still there. But I thought it stood up." He took his 13-year old son to see it, which must have been a bit embarrassing, on both sides, but they had a good conversation about it afterwards. He also took him to see the Alan Partridge film, which they both thought was brilliant. "With any revival, any old thing coming back, you feel your age profoundly and powerfully and unsettlingly… When you get older than your own play, it's very strange."

Having rediscovered writing and directing, Marber also returned to performing, with a cameo in The Vote at the Donmar last month. It was his first stage outing since Speed-the-Plow in 2000 and it gave him a shot of adrenalin he realised he had been missing. Strange, given that he still has nightmares about his early years doing stand-up. "It's always the same. I'm behind the curtain and they call my name and I've got no material, I'm walking out there with nothing..." The reality was no less terrifying, he recalls. "It just ruined the day. All it was was fear, for about eight to 10 hours, then the gig for 20 minutes, then the relief for about four hours after and then the fear starts again. It's no kind of life. But I did love it. The fear is necessary and beautiful." Which is of course a quintessentially Marberish thing to say.

'The Red Lion' to 30 September in rep; 'Three Days in the Country', 21 July to 21 October, in rep, National Theatre, London (020 7452 3000; www.nationaltheatre.org.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks