How can a Greek tragedy help Mosul heal?

One Swiss director wrote a tragedy based on the war-torn suffering inflicted by Isis. He took it to Mosul, Iraq, in an attempt to help the nation grieve and then begin to heal, writes Alissa J Rubin

In this war-battered city, acting students pick their way to rehearsals over chunks of concrete, avoiding stairs that might give way, circumnavigating puddles of fetid water and always keeping their distance from men with guns. No one can be trusted, not even those in uniform.

“We do not need to act a tragedy,” says Mustafa Dargham, 19, gesturing at the blasted shell of the former Fine Arts Institute as he takes a break from rehearsals of The Oresteia, the ancient Greek trilogy by Aeschylus.

“This play is just talking about the reality of Mosul,” he adds.

Dargham is appearing in a version of The Oresteia, adapted by Swiss theatre director Milo Rau and his NTGent theatre company based in Ghent, Belgium.

While Greek tragedies go back 2,500 years, theatre directors continue to find them extraordinarily resonant today, sometimes staging them in contemporary settings or finding other ways to emphasise how pride and passion, ancient or modern, can bleed out and leave a society in ruins.

Rau takes it a step further. In a provocative manifesto he issued when he took over the theatre, he pledged to rehearse or present one show a year in a conflict zone. His overarching idea is to redefine theatre, so that even classics are reconceived for a 21st century marked by war and terrorism.

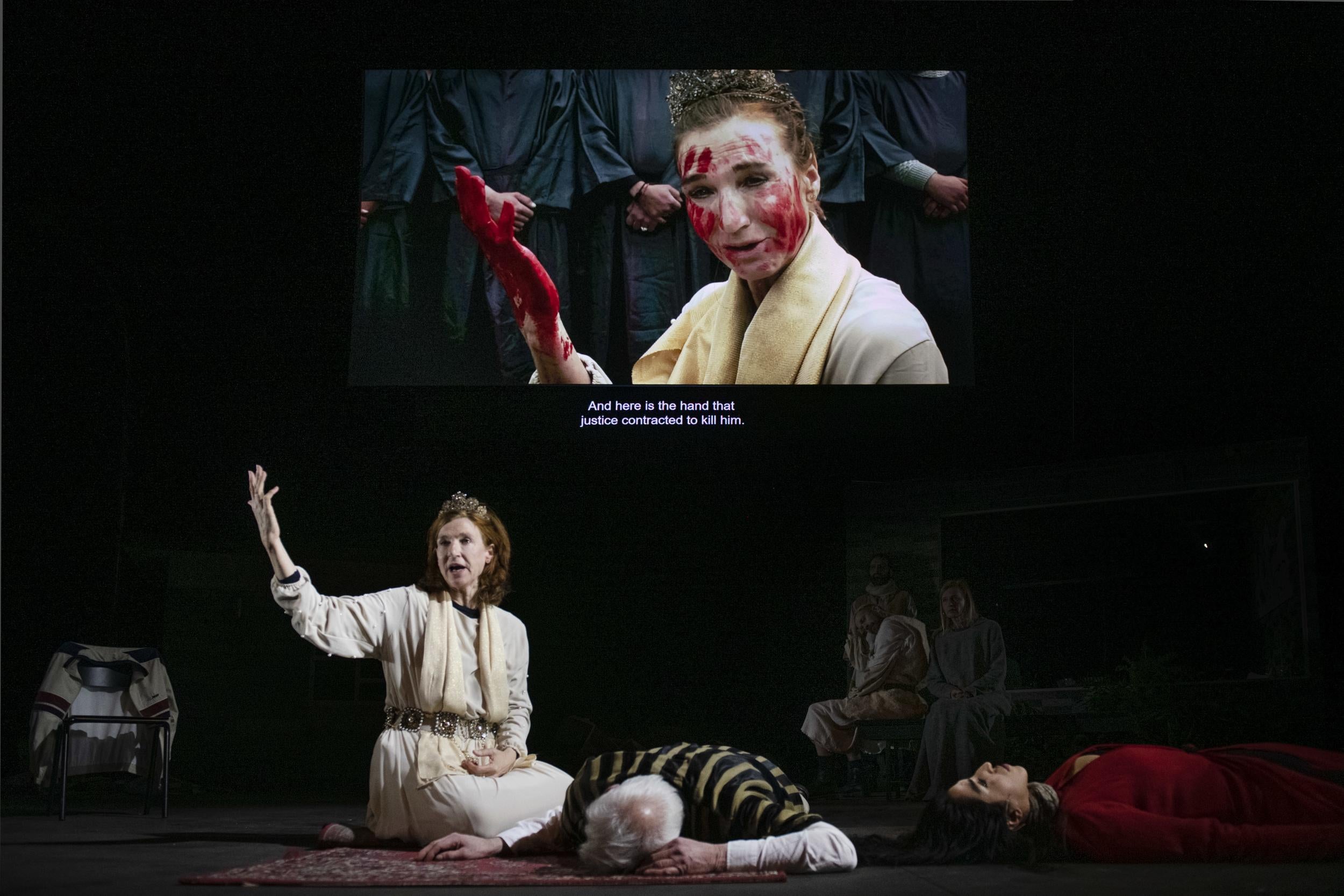

In this case, he endeavours to fuse the tragedy of Mosul with that of the House of Atreus, the dynasty at the centre of the trilogy. His version, Orestes in Mosul, focuses on an eternal theme: the cycle of revenge and the difficulty of exorcising it.

In Rau’s treatment, Mosul all but becomes a character, testimony to the devastation that revenge leaves in its wake and to the obstacles – physical and spiritual – to reclaiming civilisation.

Iraqi actors cannot easily get visas to the west, so the full production will combine video clips of them discussing and rehearsing the play in Mosul with live performances by seven European actors, two of whom are of Iraqi origin.

“I wanted to do what tragedy means, where every decision is wrong, where there is no good choice,” says Rau. In many ways, he could not have come to a better place to show that.

Here Isis’s invasion, takeover and defeat resulted in a city of victims and perpetrators, and some who were both at once. It is a place where suspicion is rife, informers are everywhere, and daily life is painfully hard.

Yet a week spent with Rau and his European team, as they work with Iraqi performers, also demonstrates how his assumptions are challenged on the ground, often putting in sharp relief how far apart Iraq and Europe are when it comes to attitudes towards homosexuality and the role of women.

Rau’s world of European theatre – highly intellectual and restrained – and that of Mosul, where acting styles incline towards melodrama, often seem far from each other but then would unexpectedly click, finding an exhilarating synergy.

Actors like Dargham, who plays a member of the chorus, say they saw Rau and his team arrive with preconceptions, mainly about the Islamic State’s invasion, but were seemingly oblivious to other painful episodes.

Since the “Belgian group”, as he called them, did not ask, he never mentioned that his father, an Iraqi army colonel, was killed by al-Qaida when Dargham was barely 10 years old.

Here Isis’s invasion, takeover and defeat resulted in a city of victims and perpetrators, and some who were both at once. It is a place where suspicion is rife, informers are everywhere, and daily life is painfully hard

Similarly, since Rau never inquired, he did not mention the daily difficulties that he says many of his classmates face. “They did not ask about water, about electricity,” he says.

But Dargham ultimately chose to give the Europeans the benefit of the doubt. “I am sure they asked somebody else,” he says.

Finding a method in the madness

The first day of rehearsals begin with the NTGent team dragging a large table into the bare courtyard of the building now being used for the institute’s theatre programme. Stefan Bläske, the dramaturge, and Rau set up their computers at one end of the table, working on the script.

Rau’s approach to scriptwriting is loose, and with Orestes in Mosul, as with many of his other works, he mixes sections of the original text (no more than 20 per cent, in accordance with another tenet of his manifesto) with material gleaned from his team’s research and discussions with the actors. In this production there will also be music and documentary video clips of the Iraqi actors discussing the play.

With little electricity available, members of his team watch as power bars on their computers dwindle over the course of a morning. Plumbing is provisional as well. But at midday, spirits rally a bit when someone brings a box of local baklava and plastic cups of dark, heavily sugared Iraqi tea and bottles of water.

Attempts to figure out the daily schedule are largely futile. And for the Iraqi actors it is hard just to show up on time.

Mosul is still a barely functioning city, where most residents fear they are about to tumble back into war. Getting from the west bank of the Tigris to the east, where rehearsals take place, can take hours, as only two bridges are functioning, and only in one direction at a time.

On subsequent days when rehearsals move to the former arts institute building, which was bombed during the war, students have to walk through a crowd of silent, grief-stricken families outside the city’s morgue. They are waiting for the bodies of daughters, sons, brothers and sisters who drowned when a pleasure boat capsized.

For those who loved Mosul, one of the most cultured cities in Iraq, Isis’s rule stole not just their way of life but their city’s soul. Books were burned, art banned, all pleasures prohibited.

At the former home of the arts institute, which had been occupied by the Islamic State, the scars are everywhere.

Mosul is still a barely functioning city, where most residents fear they are about to tumble back into war

The sculpture teacher who now works in a small intact building nearby says he broke his own works to avoid watching Isis fighters smash them. The school’s custodian, who still lives on the grounds, hid some of the students’ paintings under the wreckage of a nearby bombed house to preserve them.

In the building where Rau films for three days, the costumes of productions past are all but buried in the wreckage, damp from holes in the roof and walls where the rain blows in.

Suleik Salim Al-Khabbaz, the director of the institute’s theatre programme, who plays the oud in the NTGent production, points at a long twist of beige hair that is almost camouflaged by the concrete dust.

“Ophelia’s hair,” he whispers, adding, “I was Hamlet.”

He points at something that looks unnervingly like snake skin. “My chain mail,” he says proudly.

“And that,” he adds, as Rau steps over a triangle of wires, “was the inside of a piano, a beautiful piano.”

He shakes his head: “Isis is the worst weapon that human beings created.”

“It is a weapon we created against ourselves, but Mosul is not Isis,” he adds. “This is my message to the world. Please, do not think of Mosul as Isis.”

Teaching, learning, disagreeing

For the theatre students, most of whom have never read The Oresteia, it takes a whiteboard to diagram the plot, characters, and what was at stake.

In brief: Agamemnon, who has sacrificed his daughter to speed his journey to the Trojan Wars, returns after 10 years, only to be killed by his wife in the first play. In the second, their son Orestes and daughter Electra discover how their father died, and Orestes takes revenge on their mother and her lover.

In the final play, Orestes is pursued to the temple of Athena by the Furies, ancient goddesses who want him to pay for his mother’s murder. There, Athena presides over his trial; ultimately it is the citizens of her city, Athens, who pass judgment on him.

Johan Leysen, 69, a well-known Belgian screen and stage actor, is on site to play Agamemnon. But he has also taken on coaching the students. With help from German-Iraqi actor Susana AbdulMajid, who plays another character, Cassandra, and whose family is originally from Mosul, he tries to draw the complicated family trees and explain the role of the chorus in Greek drama.

He spends breaks with the young performers, herding them to rehearsals and working to harmonise their theatre training – which involves a great deal of stylised dance – with the movement and expressions more familiar to European audiences.

Leysen, who had a role in another of Rau’s productions, seems to intuit what the director is looking for but shows humility about the difficulties of working across cultures.

“I have no illusions that in the two weeks here, I will understand anything – I am a tourist, a foreigner,” he says softly.

Yet, he says, he respects Rau’s on-the-ground approach, which he attributes to the director’s early training as a sociologist.

“Milo does not go somewhere for confirmation of what he thinks,” says Leysen. “It’s a floating dramaturgy. The testimony of the people here and the process of asking questions, about codes, that creates it,” he says of the play.

Rau says he is struck by how “identity politics” shapes behaviour among the Iraqis, especially when it comes to gender and sexuality.

“This is the first time I have really been confronted with young, clever artists and what is possible for them and impossible within their culture,” he says.

This is the first time I was really confronted with young, clever artists and what is possible for them and impossible within their culture

One of the Iraqis who brings this home is Baraa Ali, a 19-year-old theatre student who has been cast as Iphigenia. She is on the fence about being filmed because she fears that people she know will eventually see her performance.

Khitam Idress, 59, a teacher and part-time actress here whose husband was killed by al-Qaida, is playing Athena. She is among those urging Ali to say yes, so that her participation can show the world that a young Iraqi woman could be a performing artist.

But Ali, who wears her hair covered, isn't sure: “My family will allow me to do it, but our society cannot accept it,” she says. “Boys are allowed to act by the society, but not girls.”

Finally she agrees to be filmed, but only if she can render herself invisible by wearing a niqab that has just slits for her eyes.

Things get heated

An aspect of the production which predictably causes a stir is Rau’s decision to have Orestes and Pylades, best friends in the third part of the trilogy, kiss each other on the mouth.

A western actor and an Iraqi actor based in the Netherlands are playing the two men. Some of the male Iraqi theatre students, who play the Furies, are uncomfortable, even angry, when asked to be present for the scene.

All week, the Europeans and the Iraqis hash out – or try to – the difference between a stage kiss and a real kiss. But several young actors express worry that it is “against our religion” – or will be seen by their community as tolerating overt homosexuality, which many in Iraq view as aberrant.

Finally Rau agrees that there will be a kiss but it will be modified. However, the final version, which is captured on video, still struck many Iraqis watching it as too explicit.

The last scene of the play – the trial of Orestes – is one in which Rau and Bläske’s vision of theatre spanning worlds proves especially gripping.

Aeschylus asks whether Orestes should suffer death for killing his mother, or be forgiven, with a jury of Athenians rendering a final decision. In the version of the last scene recorded on video, Dargham and seven of his schoolmates, playing the jury, come to a split decision on Orestes’ fate.

Idress, who plays Athena, draws herself up to her full height of 5 feet as she stands in the wrecked fine arts building. She seems to grow in stature as she announces, “My vote goes to peace. The chain of killing must come to an end.”

In that moment, it seems a vote for life, for hope, for the city of Athens and for the city of Mosul.

But Rau does not shirk the tougher question: What happens when the vote is about something real and the jury knows the victims’ suffering personally?

In video clips with the same jury of theatre students discussing the fate of Isis killers, the anger and passion is real. “As they sentenced us to death,” one student insists, “they should be sentenced to death.” Another countered that the decision should rest with the courts.

When it is time to vote, not one raises a hand for the death penalty, but not one votes for forgiveness, either – explaining a little about why it is hard to stop the cycle of vengeance.

Two days later, Rau and his team are packed and heading home to Europe, where Orestes in Mosul is to open on 17 April at NTGent.

Rau’s work is regularly performed at major theatre festivals; the New York University Skirball presentation of Five Easy Pieces, about a notorious Belgian pedophile, marked his American stage debut in March. Orestes in Mosul has tour dates scheduled across Europe through the end of the year.

At the end of his 10 days with the NTGent group, Dargham, who joined the institute’s acting programme by chance, says he now wants to be an actor. Still, he says, he thinks he would prefer comedy to tragedy.

“The experience was difficult at first,” he says, speaking for his classmates as well. “But we loved the Belgian group and loved working with them.

“When they finished and travelled away,” he adds, “they had touched us, and we felt lonely.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks