First Night: Hamlet, National Theatre, London

Here comes the son, with ghosts of Hamlets past

A great Hamlet is not only a Hamlet for his time, it can be a Hamlet that defines his time. John Gielgud was the lyrical romantic in the 1930s, David Warner the rebellious student in the sixties, David Tennant a mercurial adolescent for the “whatever!” generation of teenagers in the noughties.

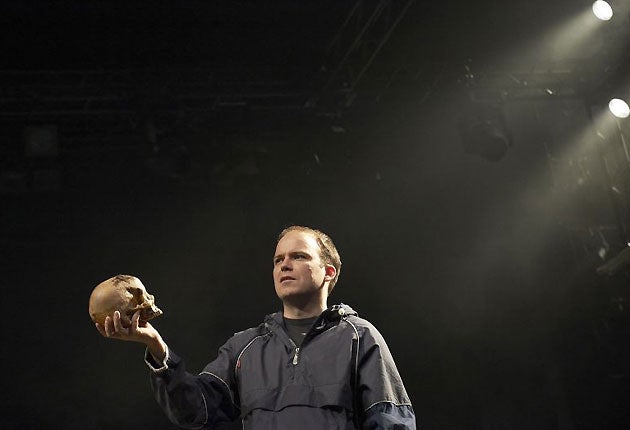

It was intriguing to know how the National’s artistic director Nicholas Hytner, directing his first Hamlet, and Rory Kinnear as the prince would define our own age. Kinnear, son of the late comic actor Roy, must be one of the least famous names to play the role, but Hytner earmarked him for it more than two years ago.

Initially, it’s not altogether easy to see why. Sat in his dark suit, the wiry figure with receding hair looks, as do many of the cast, a little like a gangster in a Guy Ritchie movie. His initial lines and first soliloquy do not suggest the towering performance that is to come.

Hytner’s Denmark in this modern dress production (part of the Travelex £10 ticket season) is a surveillance state. The set is a large room framed by large doorways, themselves usually framed by a security man with an earpiece. It is rare for two people to have a conversation on stage alone. Nearly always someone is watching, listening, moving off to file a report.

David Calder’s excellent Polonius is not the bumbling fool we sometimes see, but the spymaster general. With an imperceptible nod of the head he sends three agents at a time off to do his bidding. When he tells one to keep an eye on his son Laertes in Paris, it is not the worried, doting father, it is the chief apparatchik who demands to know everything.

In this world where everything is watched and noted, Patrick Malahide’s cold, unremorseful and unrepentant Claudius is utterly convincing as a man who would kill his brother, usurp the crown, and run a state with a mixture of paranoia, steely control, mistrust and snooping that would put Richard Nixon to shame. His henchmen are everywhere. Osric, despite Shakespeare’s own direction, is not here a fop, but a weary, efficient enforcer, knowing full well the likely result of the fight he is ordered to arrange between Hamlet and Laertes. Ruth Negga’s feisty Ophelia, after she goes mad, is trailed everywhere by two government agents, making one wonder, again for the first time, whether her drowning may have been more than suicide or an accident.

Against all this Rory Kinnear presents Hamlet as the ordinary man. There is little noble about him, little evident that is “likely to have proved most royal” despite what we are told. He is a loner, his friendship with Horatio more understated than usual, struggling to work out a battle plan against insuperable forces and after his encounter with his father’s ghost (tellingly played by James Laurenson as a fixer who would have been no pushover himself as head of state).

And then something remarkable happens. Hamlet welcomes the travelling players and watches the player king feign grief. The ensuing soliloquy “Oh what a rogue and peasant slave am I” is spoken with a sorrow and determination that has you on the edge of your seat. What is remarkable is that not just Hamlet changes, but Kinnear’s performance seems from that moment to change. The timbre in his voice seems to grow richer, his quicksilver movement more alarming. Certainly, it is hard to take your eyes off him.

His descent into madness or assumed madness is rather a descent into depression. Hytner has rightly paid much attention to the line “I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself the king of infinite space were it not that I have bad dreams.” Kinnear shows a Hamlet whose depression can be seen in fits of unwarranted aggression, withdrawal, manic high-pitched laughter, intense unhappiness or simply desperate attempts to make sense of anything, as in his the pure puzzlement that he puts across in the “to be or not to be” soliloquy, delivered while smoking a cigarette (a useful prop actually as inhaling and exhaling provide distinct pauses in which to contemplate the hereafter).

In a supporting cast which has many strengths and one or two weaknesses, special mention must be made of Clare Higgins’s revelatory Gertrude. Predictably, this marvellous actress redefines the role. Gone is the weak, lovestruck, pliable and guilt-ridden mother and wife. This is more realistically a self-assured woman, who will have a drink when it suits her, is more than capable of barking out orders herself and knows exactly what she wants out of life. In the confrontation scene with Hamlet, where often she is played as a frightened wreck, this Gertrude raises her hand to clout her impertinent son.

Yet Kinnear’s Hamlet is no adolescent. The actor looks all of his 32 years. His Hamlet is an adult, the ordinary adult stripped of all nobility in a self-destructive battle to make sense of life in a suveillance state that denies him trust, friends and love. If it is a Hamlet for our age, then things are bleak indeed. It is certainly a chilling production that demands to be seen.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks