Shadowlands review: Sanitised production can’t capture the darker realities of mortality

Hugh Bonneville brings plenty of affable charm to his role as the ‘Narnia’ author CS Lewis, but it’s an unstintingly mild-mannered performance in a deeply joyless play

At the end of CS Lewis’s classic Narnia series [spoiler alert], the children find out that they’ve died in the real world – and that the magical land they’ve been having such wonderful adventures in is actually a version of heaven, where they’ll live for ever. If you find that idea at all disconcerting or mawkish, then don’t dream of setting foot in the heavily moralistic, intensely sentimental world of film-turned-play Shadowlands. It opens with a gown-clad Lewis sermonising that real life is a shadowy land compared with the golden rewards after. Then, it shows him testing his faith to its limits, when his late-blooming love affair takes a tragic turn.

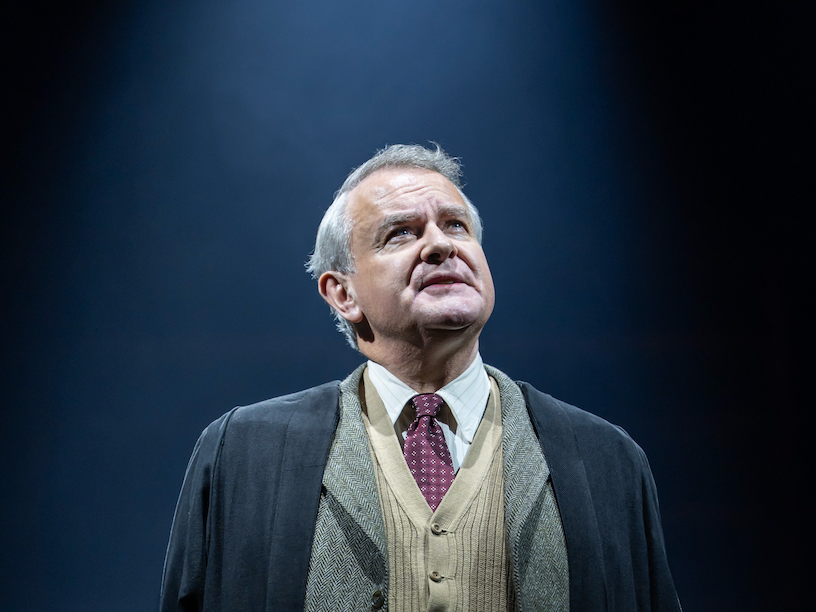

Television’s favourite nicely brought up Englishman Hugh Bonneville (Downton Abbey, Paddington) brings plenty of affable charm to this devout, emotionally repressed character, but neither this sanitised production nor his unstintingly mild-mannered performance can capture the darker realities of grief, sex and mortality.

The real CS Lewis had a personal life that was a lot more complicated and colourful than his sermons. Despite preaching about the joys of marriage, he cohabited with a woman (and her young daughter) for decades, and scholars who’ve scrutinised his diaries reckon it’s pretty clear they were lovers. Here, writer William Nicholson brushes this awkward biographical reality under the carpet. Instead, he paints Lewis as a lonely little boy in a tweed-suited, middle-aged gentleman’s body. When he meets married American poet Joy Davidman (the vivacious Maggie Siff), she’s portrayed as the first female interloper to enter his bachelor pad – and when they finally tie the knot, she must tenderly reassure him that he can still kneel down to say his prayers in his PJs, unmolested.

Still, if you can resist the temptation to be cynical, these early scenes are pretty charming. Siff captures all the gauche impulsivity of a woman who set sail from New York just to take tea with her literary idol, and who carries her poems inside her like an unexploded bomb, to be defused carefully in a controlled environment. She’s a dangerous addition to Lewis’s staid social set: learned men who cluster in his book-lined house like black-gowned crows, pecking away at dusty matters of literature and theology. Timothy Watson stays just the right side of panto villain as the meanest of them, Sir Christopher, who sees women as unreasoning creatures to be avoided at all costs. Needless to say, Lewis disagrees.

.jpg)

He bonds with Joy over poetry: “Desire is a baby” and it must be fed, they tell each other, quoting 16th-century poet Sir Philip Sidney as justification for their increasingly modern relationship. They take tea, and she slips her way into his life, awkwardly third-wheeled by the brother he lives with. Then, tragedy forces this couple out of their shadows.

Rachel Kavanaugh’s production injects little notes of magic – a forest beyond the bookshelves, softly falling snow – that help suggest the imaginative landscapes that Joy and Lewis tread together. But there’s still something deeply joyless about this play’s reluctance to show the couple actually being happy together before they descend into a world of hospitals and misery. It’s as though the knowledge that Joy is a scandalously divorced woman (and thus ineligible for traditional Christian marriage) means that Nicholson can only justify depicting their love when the character is at death’s door.

The bleaker second act swaps flirtation for a heavily romanticised depiction of Joy’s suffering, complete with melodramatic cries of agony and much-discussed crises of faith. There are audiences who’ll lap it all up as an emotive alternative to a church sermon, but they deserve better. Real life is much more complicated than the fridge magnet quote-worthy moralising that fills this play’s later scenes, and an author with the imaginative power to turn God into a friendly lion would have understood that.

‘Shadowlands’ is on at the Aldwych Theatre until 9 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks