Young Marx, Bridge Theatre, London, review: Rory Kinnear is on glorious form here

Nicholas Hytner and Nick Starr open the doors to their brand new theatre with a show that reunites the team behind one of the biggest smashes of that era, 'One Man, Two Guvnors'

A warm welcome to the Bridge, the first wholly new, large-scale commercial theatre to be built in London since 1937 (if you except Shakespeare’s Globe, which opened its doors in 1996). It’s the brainchild of the two Nicks – Hytner and Starr – who were a formidable combination as, respectively. artistic and executive director of the National Theatre between 2003 and 2015.

Hytner has talked in interviews about the “sweet spot” between creating new, challenging work and pulling in a large audience. His instinct for intelligent populism was one of the glories of his regime at the NT, generating such hits as The History Boys, War Horse, and The Curious History of the Dog in the Night-Time.

Now this new venture gets off to a whizzing, witty start with Young Marx, a show that reunites the team behind one of the biggest smashes of that era: One Man, Two Guvnors. Richard Bean – co-writing with Clive Coleman – has come up with a wily, fast-paced comedy that presents us with the author of Das Kapital not as the venerable economist of later repute but as the 32-year-old refugee, chaotic. penniless and newly arrived in Soho where he is crammed in a two-room flat in Dean Street with wife, children and maid. On the run (up chimneys and over roof-tops) from creditors and spies, Europe’s most feared terrorist has mislaid his mojo – his writing is blocked, his marriage is on the blink, and his pal Engels (presented here as the other half of political economy’s most noteworthy music-hall double act) is wretched that our endlessly procrastinating genius has applied, in desperation, for a job as a railway clerk.

Situated on the river near City Hall and Tower Bridge, the new theatre has been designed for maximum flexibility. The handsome 900-seat auditorium is in an end-stopped formation for this piece but the modular seating can be shifted so as to accommodate multiple configurations (promenade, thrust stage etc). This is one of the crucial ways that the venue – funded by venture capital to the tune of £12m but not in receipt of government subsidy – comes as a bracing kick up the rear for the West End and conventional notions of theatre-going.

The Bridge has the capacity of some Shaftesbury Avenue theatres, combined with the shape-changing adaptability of the Dorfman, the studio space at the NT. No one is denying the architectural beauty or atmosphere of the old commercial playhouses. But, thinking from scratch about what an unsubsidised 21st century theatre might look like, the creators of the Bridge have freed themselves to concentrate on nurturing new writing, uninhibited by the restrictions of those fixed proscenium-arch stages. Their policy is an inspiration to dramatists to think big. The National may be watching with some trepidation.

Of the shows that have been announced, the only classic is a cut-down promenade version of Julius Caesar, starring Ben Whishaw as Brutus, in which 400 audience members will play the Roman mob. Apart from that, it’s all new work – with half of the repertoire coming from excellent female playwrights: Lucy Prebble, Sam Holcroft and Nina Raine whose play about JS Bach will star Simon Russell Beale.

Hytner’s bulging address book of great actors who either have worked or are keen to work with him is obviously no handicap to the Bridge’s mission to attract large audiences for unproven fare at affordable prices. The tickets cost £15 to £65, with some premium seats, for admission to an auditorium with raked stalls and stacked galleries that ideally combines the epic with the intimate. The one thing that needs to be corrected is the rate at which this auditorium can be entered and exited. At present, it’s too slow (the doors are narrow) and causes irritating queues.

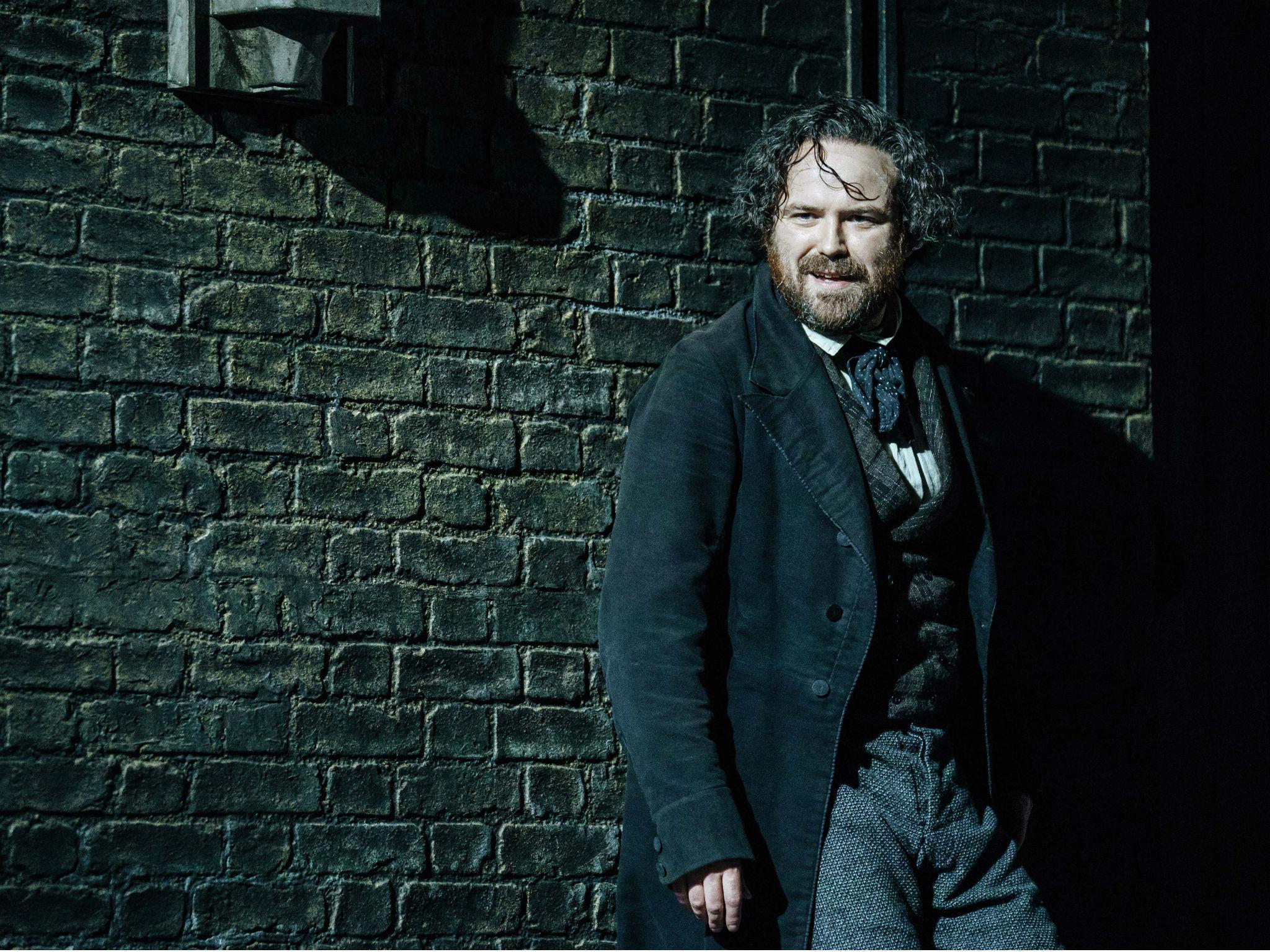

Rory Kinnear (who played Iago and Hamlet for him at the National) is on glorious form here – believably both a high-powered intellectual and a greasy-maned, emotional disaster area – in the title role in Hytner’s sharp, spry production of Young Marx. Boozy, running out of things to pawn, and beset by equally unwelcome spies, bailiffs, fawning acolytes, and rival revolutionary factions advocating the terror tactics that he himself opposed, this hapless Marx might seem too farcical to be true. But the ironies, grist to Bean’s mill, are all based on fact. His wife Jenny (whose sorely tried, restive loyalty is beautifully caught by Nancy Carroll) really was the sister of the Prussian minister for the interior who, after an assassination attempt on King Frederick William IV, set spies on political exiles in London – with especial reference to Dean Street. His collaborator Friedrich Engels (attractively played by Oliver Chris) really did work at his father’s Lancashire cotton mill and rifle the petty-cash in order to fund Marx who – despite his prodigious theoretical grasp of finance – was too poor to pay the medical bills for his chronically sick little boy.

Mark Thompson’s fine compact design of a brick cube topped with a puffing chimney-scape rotates and opens up to reveal the various settings (the British Museum reading room that becomes the site of a saloon brawl; the upstairs function room of the Red Lion, meeting place of the factious emigres et al) where the story nimbly unfolds Though the show won’t disappoint fans of Bean’s flair for one-liners and farcical slapstick, this is not One Man, Two Guvnors Rides Again. Marx may be (in Engel’s words) “a solipsistic, self-regarding prick” who unscrupulously tries to make his chum carry the can (and save his public reputation) when he impregnates the devoted family maid (deeply affecting Laura Elphinstone).

But the play can’t be summed up as a larky diminution of the protagonist; rather the reverse, you could argue. It takes his dialectical materialism seriously in many witty allusions. Whether he is correctly predicting the commodification of Christmas or – in a stirring speech – inaccurately foreseeing the downfall of capitalism in just such a market crash as we have all recently lived though, you never doubt the sincerity or tenacity of his vision, qualities magnified by the unpropitiousness of the circumstances.

And what makes the piece especially timely is its adroit portrait of an open London where refugees were welcomed and where a wanted man like Marx, in flight from the wave of 1848 revolutions in Europe and mistakenly branded a terrorist, could escape arrest or extradition. An appetite-whetting start for a bold, risky venture that has its priorities right and deserves success. Did I mention that the Bridge has a vast, welcoming foyer and will mount the occasional musical? Or that Young Marx will be broadcast by National Theatre live on 7 December?

‘Young Marx’, Bridge Theatre, London SE1 2SG, until 31 December

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks