RIP to the box-set era: How streaming is letting classic TV slip through the cracks

Netflix is great... if you don’t want to watch anything made before 2010. The streaming giants have enriched the TV landscape, but so many great shows from the past are sliding from view, says Louis Chilton

How do you respond when someone raves to you about a must-see TV series? Increasingly now, the answer tends to be: “What’s it on?” The response, “Oh, it’s only on DVD” is tantamount to suggesting it can only be viewed by performing some occult summoning ritual – I mean, who has the time, or the playback device? We are sliding towards a disc-less, algorithmic future, in which DVDs and Blu-rays survive for many only as time-consuming, space-intruding throwbacks.

Of course, the streaming revolution has mostly been positive, especially to us Brits. In a matter of years, Netflix’s unflagging rise to power has seen the modern TV fanatic evolve from knuckle-dragging box-set buyer to tech-savvy streaming sophisticate. No longer do we have to kowtow to the whims of a TV scheduler, or splurge money on overpriced DVD collections, replete with half-cocked miscellanea and deleted scenes that are, more often than not, deleted for good reason.

The vaults of British TV history are open, and accessible, in a way that would have been inconceivable even a decade ago. A multitude of classic series can be streamed for free on BBC iPlayer or All 4; if you supplement their catalogues with a paid subscription or two – to Netflix, for example, or BritBox – you can enjoy a fairly comprehensive selection of essential British TV, at least from the 1980s onwards. But while it’s a treat to have ready access to treasures like Alan Bleasdale’s GBH (on All 4), the picture turns cloudier when you start to look for fare from beyond our nation’s shores.

Last month marked the 30th anniversary of Northern Exposure. Running from 1990 to 1995, the show is an affecting, offbeat drama about a neurotic doctor forced by the terms of his student loan to run a practice in a remote town in Alaska. Northern Exposure won an Emmy and two Golden Globes for best drama series, and retains an ardent, if modest, fanbase; a revival is supposedly in the works at CBS. In the UK, its anniversary passed virtually unacknowledged. This is no surprise – the series is unavailable to stream here, and the only means of seeing it (with its original soundtrack intact) is a Blu-ray box-set that costs around £100.

Northern Exposure is far from the only example. While the US has proved itself the dominant TV force over the past few decades – nothing the UK produces is likely to command nearly as many eyeballs as Friends, or Game of Thrones, or The Simpsons – older American series are being left behind. NYPD Blue, the long-running cop procedural whose fingerprints can be lifted from pretty much every police series since, is another cast-aside relic of a bygone era. Five of its 12 seasons can be purchased digitally, for £23 each on Amazon; anyone wanting to watch all 12 would have to buy the complete series on DVD for around £150. This is not some obscure cult gem. This is a series that was nominated for literally hundreds of industry awards (winning 20 Emmys), gave one-off guest roles to just about every recognisable character actor under the sun, and whose complicated, explicitly racist protagonist Andy Sipowicz was a precursor of the Noughties wave of male antiheroes.

Cop show aficionados should feel doubly aggrieved; also absent from the corridors of the UK streaming platforms is Homicide: Life on the Street, the subversive Baltimore-set drama adapted from a book by a pre-Wire David Simon. Like NYPD Blue, it also featured its share of big-name guests, including Robin Williams, Steve Buscemi and Jake Gyllenhaal. Andre Braugher, the actor whose broad deadpan has rightly endeared him to a generation of sitcom-watchers on Brooklyn Nine-Nine, is blisteringly good in Homicide, as ace detective Frank Pembleton. All seven seasons are available on DVD, at a relatively affordable price (£50), but most people, especially younger people, are unlikely to bother seeking it out.

Classic US sitcoms are just as poorly served as dramas. Seminal heavy-hitters like Cheers, Taxi and M*A*S*H are unavailable to stream anywhere freely. Some more obscure programmes, like the beloved 1990s workplace sitcom NewsRadio, or Al Jean and Mike Reiss’s post-Simpsons cartoon The Critic, have never been given physical releases in the UK, despite being decades old. Naturally, the coverage of foreign series thins out much more drastically when we look beyond the US. Netflix has given the UK access to a panoply of recent foreign-language originals, but very little in the way of older non-originals. While streaming services like Mubi and BFI Player can be a reasonably reliable source of foreign and arthouse films, there is no real equivalent for TV series; esteemed works like Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Dekalog, Rainer Werner Fassbender’s Berlin Alexanderplatz and Edgar Reitz’s Heimat all require physical purchases.

Netflix is one of the worst offenders when it comes to ignoring the past: recent research suggests 81 per cent of its content was released in the 2010s, with only 3 per cent coming from the 1990s, and 2 per cent from the 1980s. This can largely be attributed to its full-bore tunnelling into the world of original content production. Some other streaming services fare better – more than 25 per cent of the content on Disney+ dates back to the 20th century, for instance – but they’re still far from ideal.

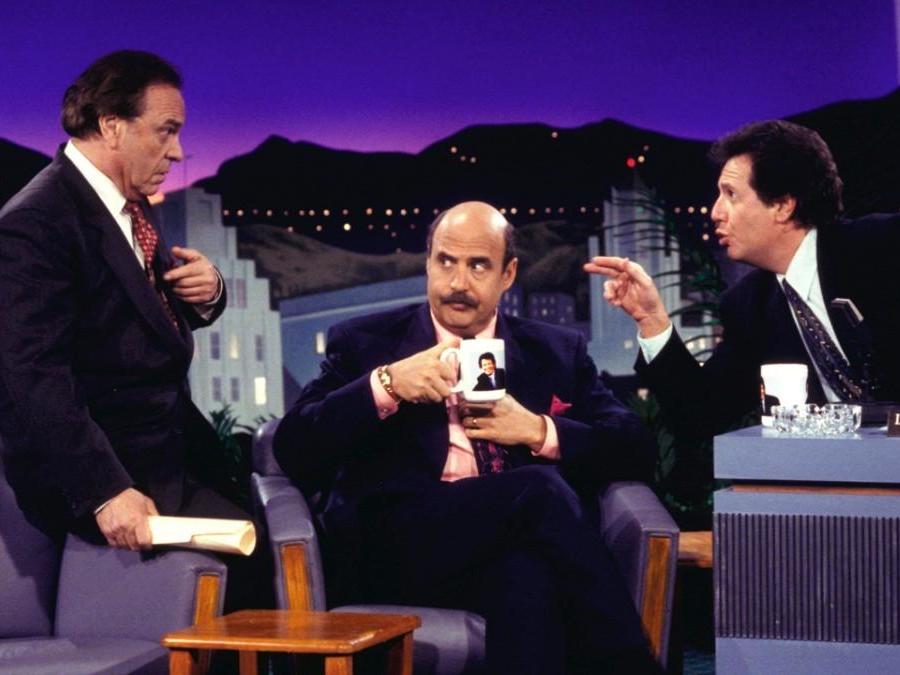

Now TV, the Sky-owned streaming service that has the exclusive streaming rights to HBO programming, does a decent job of making many of the “golden age” TV series available. The Sopranos, The Wire, Deadwood – these were the types of shows that were synonymous with the box-set era, the kind of prestige TV that redefined the medium and banished the notion that television was a lesser art form. But HBO’s older catalogue is not shown the same love. Inimitably great talk-show sitcom The Larry Sanders Show (from which Ricky Gervais would liberally borrow in making The Office) and groundbreaking sketch comedy Mr Show with Bob and David (which made cult stars of its two leads, Bob Odenkirk and David Cross) are both omitted from the Now TV streaming conveyor belt; they have never been given the chance to take root here.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

We’ve seen this happen before, of course. The artistic canons – of everything, from literature to music to film – have always been inextricably tied to accessibility. While the rise of streaming has done wonders in some regards, the omission of so many significant TV landmarks is a glaring failing, a myopic devotion to the shiny and own-branded new. There are two logical outcomes from this lack of access. Either the series will simply go unseen – a crying shame, in many cases – or the cash-strapped TV fanatic will turn to internet piracy. The ethics of digital piracy is a hotly contested issue, but I don’t imagine most people would have to perform particularly complex mental gymnastics to rationalise downloading a series like Slings and Arrows, the superb (and hard to obtain) Canadian dramedy about a haunted Shakespearean theatre director.

The streaming vs DVD divide has sometimes been compared to the modern housing market – we have transitioned from a culture of ownership to one of renting. As with renting a house, you are all too often subject to the whims and demands of a private landlord, who is under no obligation to cater to you. Netflix may refer to its content as a “library”, but it’s a far cry from a public service. Imagine a world where no libraries carried copies of Charles Dickens’ novels, or where John Steinbeck’s works could only be ordered online in editions worth £150. What a sorry sight that would be.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks