The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Can Kiefer Sutherland be US president, please?

With Donald Trump flailing around in the world of politics and Hilary Clinton not doing much better, it is time to look to fictional drama to find a suitable alternative for president, including Sutherland on ABC’s ‘Designated Survivor’

To many, the 2016 campaign for the US presidency has been dispiriting and miserable, featuring the two most unpopular candidates in history. Thanks to the fascistic buffoonery of Donald Trump, it has been characterised by a tone that has swung wildly from facetious to obnoxious to disgraceful and back again.

At times it has felt like a hideous nightmare, an election imagined in a dystopian future in which Trump, a reality TV star with no experience or qualifications to be president, could yet win. It has felt like something dreamed up by a Hollywood screenwriter with a dark sense of humour.

Because American cinema and television are not ashamed of dealing in Trump’s currency of populism in their treatment of politics, “anti-political” candidates have frequently been put on screen as a means of indulging the desire of audiences for something different from the politicians they are served up in reality.

In comedies from Frank Capra’s Mr Smith Goes to Washington (1936) to the more recent Head of State (2003) and Man of the Year (2006), Hollywood has revelled in the fantasy that the “ordinary Joe” can storm the barricades of the establishment and change things for the better. These films fulfil a desire for authenticity in politics, where candidates are unvarnished truth-tellers here to deliver the “will of the people”.

But it would seem that, in 2016, this equation has been flipped on its head. Trump has changed the game. He is a Hollywood comedy (or horror, depending on your perspective) blundering around in the real world of American politics.

So perhaps we can look to fictional drama to find a suitable alternative to him.

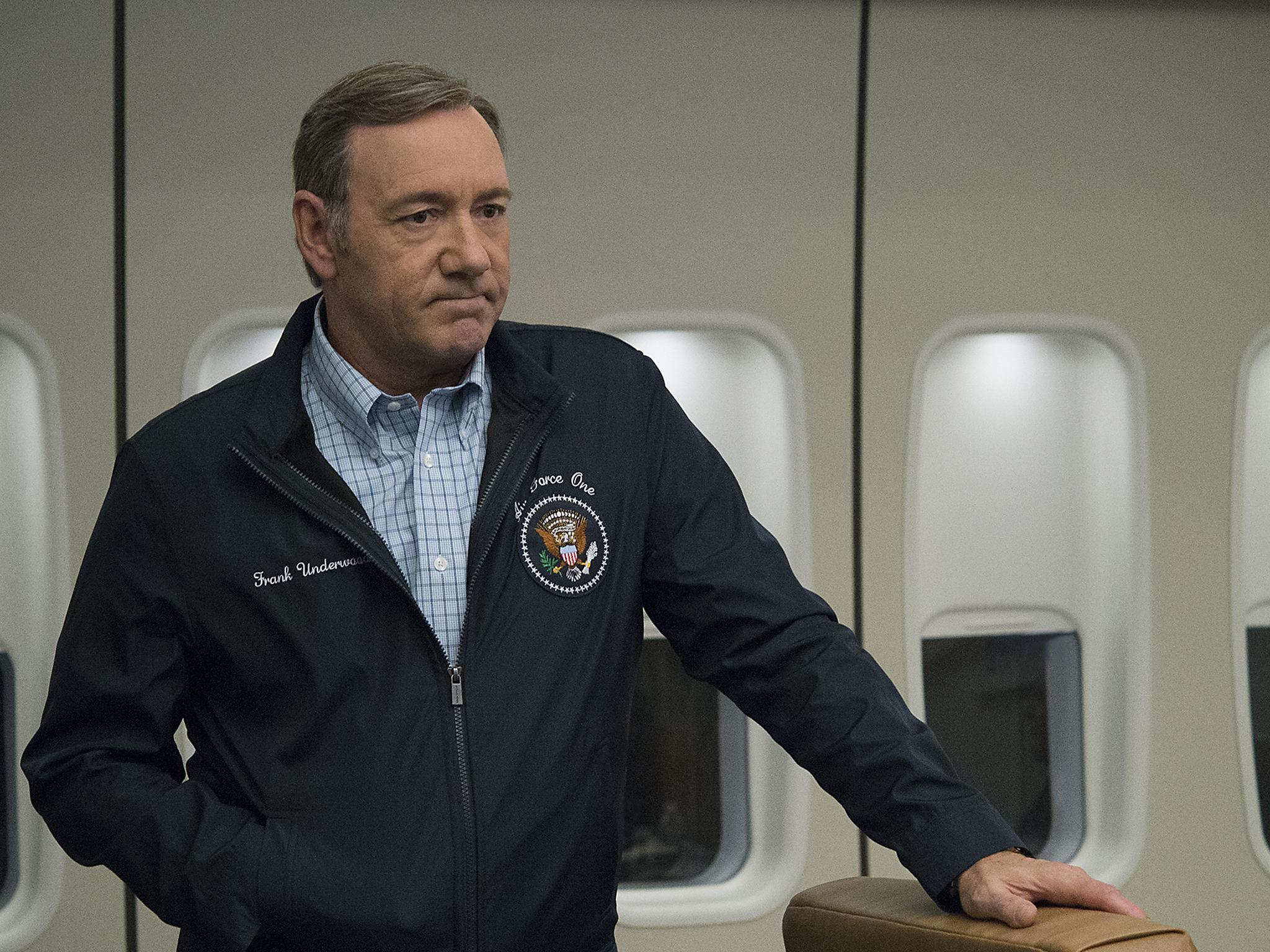

Television drama has, for the past few years, viewed the presidency with some cynicism. Shows like Scandal and House of Cards have not only explored the corruption within the political system but also questioned what the presidency is for, and even whether it is worth having at all. The tiresome bargaining, compromise, shady deals and questionable allies that are intrinsic to politics are here for all to see. All this renders the president a weak, impotent, frustrated individual who either would happily give up the job for love (Scandal) or resort to extraordinary levels of corruption to inject it with some power (House of Cards).

As I argue in a chapter of a new book on this topic, these recent fictional treatments of the presidency show the US’s problems to be considerably more intractable and complex than you might think if you listened to somebody like Trump (or, for that matter, Bernie Sanders). It is why new ABC show Designated Survivor is the most interesting of the recent political crop, drawing as it does an obvious contrast between contemporary presidential fiction and reality.

Kiefer Sutherland plays Tom Kirkman, a secretary of housing and development suddenly turned president when the Capitol Building is blown up in a terrorist attack occurring during the State of the Union address. As the “designated survivor” – the government official asked to remain in a secure location during this event who will be next in the line of succession should the unthinkable happen – he has the constitutional duty to assume the presidency after the attack.

He has no experience of high office, let alone the ability to provide a response to a major terrorist incident on American soil. He is perceived as illegitimate, weak, intellectual rather than decisive (because – and, believe it or not, this is a common trope in presidential fiction – he wears glasses). But unlike the recent, hyperviolent revenge fantasies Olympus Has Fallen (2013) and White House Down (2013), Designated Survivor prescribes a sober, measured and careful response to the attacks. Kirkman is restrained, thoughtful, and unwilling to act until he is absolutely sure of who has done this and why.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Sutherland is perhaps best known in recent years for his portrayal of counterterrorism agent Jack Bauer in 24, the television show that captured the post-9/11 zeitgeist after 2001 and arguably provided popular cultural justification for the extreme policies pursued by the Bush administration. So the fact that Kirkman is played by Sutherland speaks to this rather radical shift in the fictional presidential imaginary.

In Designated Survivor, Jack Bauer is president, but one who appears to have learned the lessons of his predecessors. He has the temperament necessary to defend the nation in turbulent times, and he will protect the constitution, liberal values, and the rule of law. When Islamophobia rises as a result of the terrorist atrocity, Kirkman steps in. He is not really even a “fantasy” candidate, but simply a safe pair of hands (as Hillary Clinton increasingly appears to be).

The outlandish fantasy president once so popular in film and television, it seems, will no longer suffice when one of 2016’s all-too-real candidates has shown us what could happen if our dreams (or nightmares) come true. It is a laughable irony that President Kirkman – a fictional creation – could be more attuned to the dangers facing the world than a President Trump. Television drama is showing us that perhaps we should no longer hold out for a hero, but simply a grown-up.

Gregory Frame is lecturer in film studies at Bangor University. This article was originally published on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks