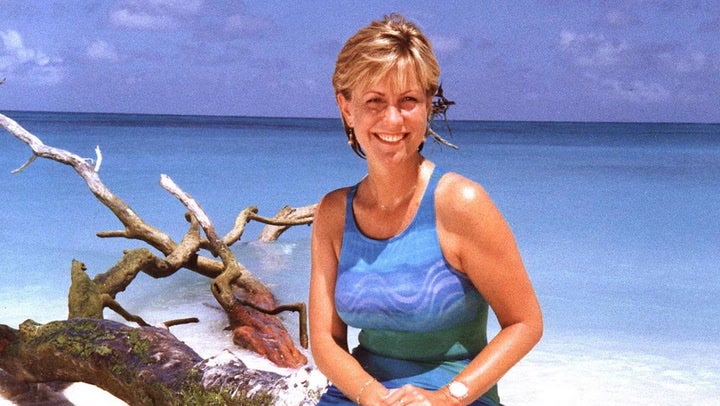

Jill Dando 25 years on: ‘Someone could still say, ‘Yeah, it was me’

Twenty-five years after the TV presenter was shot dead on her doorstep in broad daylight, rumours over whether it was a Serbian hitman or a stalker have never gone away. Here, Chris Harvey asks her brother what he thinks really happened

On 26 April 1999, Nigel Dando was at his desk at the Bristol Evening Post, where he was chief reporter, when he got a call from a contact on the Daily Mail. It was about his sister, the hugely popular TV presenter Jill Dando. “He said he’d heard that Jill had been involved in some sort of accident, and had I heard anything?” the former journalist tells me from his dining room. “It was 10 o’clock in the morning. I rang Jill to check she was OK, and couldn’t get hold of her. And then he rang back about half an hour later, and said, ‘I think it’s a bit more serious than that, she’s been stabbed in the street where she lives and taken to hospital.’”

Dando tried calling his sister’s fiancé, the gynaecologist Alan Farthing, and eventually got through to him. “He said that he was sitting in the back of a police car on his way to Charing Cross Hospital where Jill had been taken. And there was a police officer in the car, who took over the call. He said that they believed that Jill had died.”

Dando had been murdered. She had not been stabbed, although this was not known by the time her visibly shaken BBC colleague Jennie Bond had to announce the news of her death to the nation on the lunchtime bulletin. Pre-air footage shows her asking, “What shall I say?” as a producer keeps repeating, “She was 37.” She had been shot in the head at very close range on the steps of her home in Fulham. She was found by a neighbour, who called 999 and said that she thought the woman she was looking at, whose arms were blue, with blood coming from her nose, was Jill Dando, and she wasn’t breathing.

Twenty-five years later, the hunt for her killer remains one of the most high-profile, frustrating and ultimately mystifying police investigations ever undertaken in the UK. No one has been successfully convicted of her murder. And at least one crucial mistake was made early on. In 2019, lead detective Hamish Campbell told me that the emergency services’ decision to try to resuscitate Dando when she was “clearly dead” at the scene may have contaminated or destroyed forensic evidence. “There were three doctors. Any one of them could have declared her dead,” he told me then.

Last year, a three-part Netflix documentary Who Killed Jill Dando? by Emmy-winning British director Marcus Plowright reopened the case. It has not been formally reinvestigated by police since the man who was found guilty of her murder in 2001, Barry George, had his conviction quashed as unsafe by the Court of Appeal in 2007, and was found not guilty, after a retrial, in 2008.

“I knew it was coming,” Nigel tells me, in his matter-of-fact way that one suspects is part old-school newsman and part stoic – which is the word he uses to describe how their father coped with the tragedy of his daughter’s death. “I wasn’t surprised.”

Astonishingly, George appears as an interviewee in the documentary, as does Campbell, along with family, friends and associates of the presenter, other former suspects, and the celebrated (and celebrity) KC Michael Mansfield, who defended George at the first trial. He suggests that indentations on the cartridge casing found at the scene point to a Serbian gunman, implying a political assassination.

This was one of the many theories examined, and ultimately discarded, by the police in the original investigation. It was suggested that with war raging in the Balkans, the murder may have been a revenge attack linked to a televised appeal to raise money for Kosovan refugees that Dando had made in the period leading up to her murder. Others floated the idea that she was singled out by an underworld gangland figure for her role in helping to catch villains on BBC One’s Crimewatch.

When I spoke to Dando’s Crimewatch co-host Nick Ross in 2021, he told me of his frustration at the wild theories that he believed had hampered the inquiry. “I can’t tell you how frustrated I was, almost to the point of hitting my head on the wall in the early days of the investigation,” he said then. “I had gone on Newsnight, the night of Jill’s murder, and had then consistently said that whoever did this would have a personality disorder. There are many, many, many reasons why that was going to be so. But the idea, the most ludicrous idea, was that it was because of Crimewatch.”

At the time of her murder, Dando had been at the height of a television career in which she mixed reading the news with several flagship shows for the BBC. The girl from Weston-super-Mare possessed a striking ability to be herself on screen – she was natural, friendly and at ease with people of all class backgrounds. As well as fronting Crimewatch with Ross, she jetted off to exotic locations as the presenter of Holiday and had just recorded a new series as host of The Antiques Inspectors.

Her elder brother had watched her remarkable ascent with admiration and some surprise. There was a nine-and-a-half-year age gap between them, but Jill had followed in the footsteps of her father and brother by getting a job at the Weston Mercury, the local paper in the North Somerset seaside town where she and Nigel had grown up. “She stayed so long there,” Nigel tells me. “I kept saying to her, you know, there are other jobs out there, you’re qualified.” Their mother had been diagnosed with leukaemia in the early 1980s, as Jill moved into her twenties. “I think it was one of the reasons why she stayed on the Mercury for so long… she didn’t want to leave Weston,” Nigel tells me.

Their mother’s death in 1986, he recalls, was “very difficult for Jill”. They were very close; Jill had been something of a miracle child, diagnosed with a hole in the heart when she was a toddler. “My parents tried to hide it from me… it wasn’t until later that I realised how touch and go it was.” It had been picked up when Jill started to walk. “She got out of breath very quickly, and quite red in the face.”

Doctors performed what was, for the time, pioneering surgery when she was three. “The only way they could carry out the repair to Jill’s heart was effectively to stop her circulation… chill her body to slow the heart down,” he says. “They then had this eight-hour window to carry out the necessary surgery. There was no guarantee of success. My parents went to see her in the hospital a few days after the operation, and they always carried this memory of her running towards them from the end of the ward when she saw them.” It was as if she had “instantly recovered”, he says; tests proved the operation had been a success.

When Jill finally did move on from the Weston Mercury, things happened fast. “She went to Radio Devon as a station assistant, on the bottom rung really, but she quickly became a reporter and then a presenter,” Nigel says. “Then she got a job with Westward TV (now ITV West) as a reporter but was only there a few months. Suddenly, she was on BBC Spotlight, which is the regional magazine programme for the BBC in the South West – again, started off as a reporter, but was soon presenting there.

“Then came this move to breakfast TV [on BBC Breakfast Time], which I thought might have been a bit of a jump too far, because she didn’t know anybody in London. And I think she was quite homesick for a while. But again there were people who saw her talent. It was quite a dizzying rise, given how long she’d spent on the local paper.”

It was there, too, that she began a seven-year relationship with the Breakfast News editor Bob Wheaton (they separated in 1996). As the documentary, which includes an interview with Wheaton, shows, he was at a very early stage considered a possible suspect, but was quickly eliminated from the police’s enquiries. Discussing his memories of time spent with Wheaton, he says, “Bob was her boss at one stage.

He was – is – quite a driven character. I remember him coming to our place one Christmas. In those days, we lived in the back of beyond near Bath, and it was the early days of mobile telephones. I remember him sort of marching about in the courtyard outside with a mobile phone unable to get a signal, and I just had to say, ‘Bob, it’s Christmas Day, forget it. If you want to see what’s making news, just turn the TV on.’ He was that sort of character, he cared very much about his job.

Later, he remembers her beginning a new relationship with Farthing, with whom he stays in touch. “She went on a blind date with Alan. And they just clicked. They’d announced their engagement in, I think it was, the January or February of 1999, with plans to get married in September.”

Whoever killed Jill may be watching, and even after 25 years... they may just suffer a prick of conscience and put their hands up

Jill’s murder that April caused an explosion of public interest. Campbell talks of being deluged with leads and information from the start, so much so that after a year of getting nowhere, the police began following up on leads they had sidelined as less important in the earliest days of the investigation. These included two separate phone calls suggesting that a man called Barry Bulsara, who later turned out to be Barry George, had been seen behaving strangely after the murder. Campbell’s investigation notes reveal that he believed this “came too slowly to my attention”.

Of course, gearing up to deal with the scale of such a headline-generating murder took time. “I have no criticism of the police at any stage of the inquiry,” Nigel insists. Yet the most famous botched investigation in modern times – the hunt for serial killer Peter Sutcliffe in the Seventies and early Eighties – was a cautionary tale of the dangers of being swamped with too much information. Should the Met have anticipated this and thrown everything they had at the case from the moment they knew that it was Jill Dando who had been killed?

“They’d have known there would have been a deluge of information; whether they’ve got enough resources to deal with that deluge is another matter,” the forensic criminologist Jane Monckton-Smith, author of In Control: Dangerous Relationships and How They End in Murder, tells me. “They would have had a huge budget for the case, because it was so high profile and so political. They’d have had more people on it [than a regular inquiry].

And things would have been moving more quickly. The question is whether the person who was dealing out the actions recognised that a stalker should have been at the top of their list of priorities.” She evinces surprise when I ask if she’s certain that a stalker should have been at the forefront of possible suspects from day one. “With a high-profile woman? On TV all the time? Absolutely.”

What made the case baffling, apart from a paucity of witness information, was that Dando was living at her fiancé’s house and rarely returned to her own property. CCTV of her final journey – when she bought stationery and two fillets of fish, before driving to her home in Fulham – showed that she hadn’t been followed to her address, so her killer must have been lying in wait or randomly passing. Yet her infrequent visits home suggest that a contract killer would have had to carry out extensive reconnaissance of her movements, Monckton-Smith says; a stalker may have, too, but could also have been simply loitering.

The Netflix documentary detailed the circumstantial evidence that led to local man Barry George being charged and convicted of the murder, including a neighbour who identified him in the street at 7am. He was freed after it was found that the single particle of gunshot residue found in an inside pocket of a coat in his flat a year after the murder could not be relied on as forensic evidence. It is now accepted that a single particle could be picked up by one in 100 people who have come into contact with an individual who has discharged a firearm.

Campbell repeats an earlier claim that he “thought the guilty verdict in 2001 was the correct verdict”. Monckton-Smith believes “they had very little evidence”. Nigel Dando tells me it was “pretty thin”. Jill’s agent Jon Roseman tells Plowright, “If anybody… thinks Barry George did it, they need to get help.”

With unprecedented access to George, viewers were be able to make up their own minds for the first time. Does Nigel think Barry George killed his sister? He takes a deep breath. “I don’t know. Who knows? One jury thought he did. Another jury in a retrial acquitted him. He’s never really given a full account of where he was on the day in question. But as is his right, he never went into the witness box in either of his trials. So we’ll never know exactly what he was doing on that day. And his account of events can never be tested under cross-examination…”

“Mr George’s decision not to go into the witness box was probably quite a wise one,” he decides. “Unless a strong new lead comes forward, I wouldn’t put pressure on them to reopen the case.”

He took part in the documentary, he says, “in the hope that it might just jog somebody’s memory as to what they were doing on the day: they may have a vital piece of information that they didn’t think was important, or they prefer to keep hidden. They may have known the perpetrator, or whoever killed Jill themselves may be watching, and even after 25 years, although I’m not holding out too much hope, they may just suffer a prick of conscience and put their hands up and say, ‘Yeah, it was me.’”

He prefers to remember his sister as she was, when they were growing up by the seaside, eating family meals together, going down to the beach, riding donkeys and building sandcastles. “It was an idyllic childhood. I remember her as a little Mary Poppins figure, she always liked Donny Osmond and David Cassidy – she loved their music, it was a bone of contention,” he laughs. “We’d recall that in our adult years; she still liked Donny Osmond.”

“You just think about what she might be doing now. And what she did to become the star that she became.”

‘Who Killed Jill Dando?’ was released on Netflix last year, An earlier version of this interview was published in September 2023

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks