The British are coming! Again: Another grand year for the UK film industry

There has been no Harry Potter or James Bond, but we have still had a vintage year for homegrown films

In a recent speech to an industry audience at the London Film Festival, Michael Barker, the co-founder and co-president of Sony Pictures Classics, made some startling remarks. Barker suggested, almost in passing, that we are currently in a vintage period for independent and art house cinema. He also spoke of the “richness” of current British cinema.

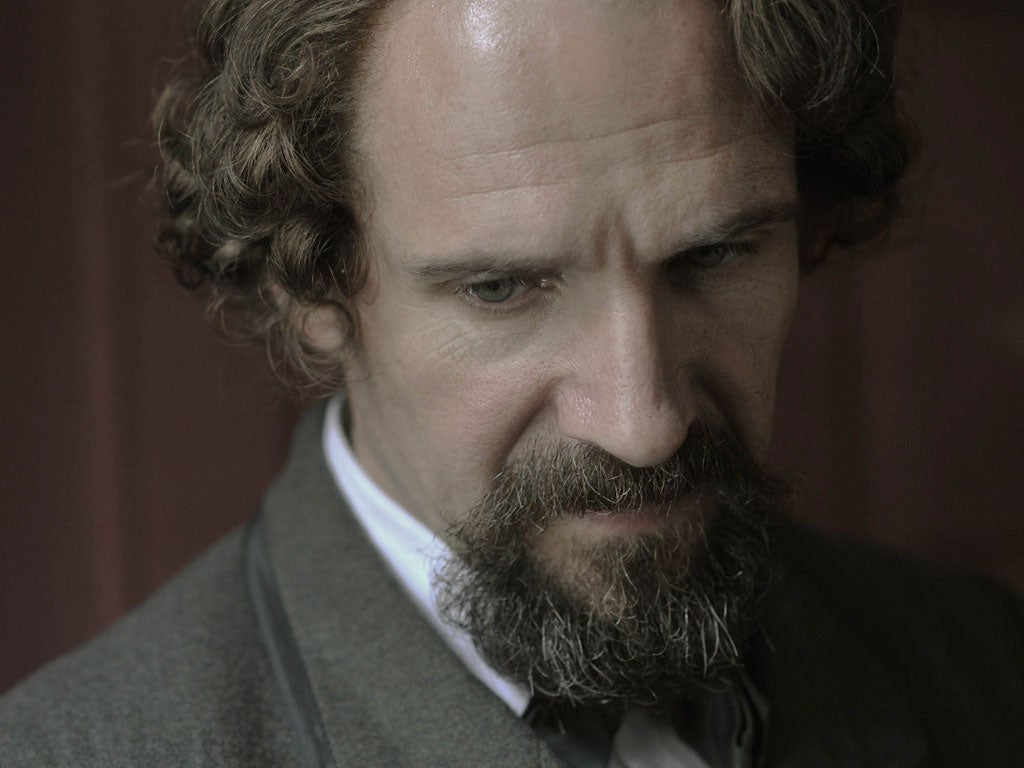

As if to underline Barker’s observations, many of the most prominent films at the London Film Festival (LFF) turned out to be by British film-makers: Clio Barnard’s The Selfish Giant, Paul Greengrass’s Captain Phillips, Stephen Frears’ Philomena, Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave, Ralph Fiennes’ The Invisible Woman, Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin, Steven Knight’s Locke, David Mackenzie’s Starred Up.

This year hasn’t yielded any equivalents to the box-office bonanza that The King’s Speech or Skyfall brought British cinema, but there have been plenty of very strong director-driven films bound to stand the test of time.

Although Barker is a far less flamboyant figure than Harvey Weinstein, he is arguably just as influential. Since he started in the business in the early 1980s, the Texan executive has co-produced, co-financed and distributed films by François Truffaut, Louis Malle, Ang Lee, Woody Allen and many other auteurs.

But his remarks went against the grain. Orthodox thinking is that indie cinema, in the UK as elsewhere, is in a prolonged slump. The economics no longer add up. Broadcasters aren’t buying movies in the numbers they once did. The box office is dominated by Hollywood blockbusters. Across Europe, public funding for film is shrinking. The DVD sell-through market is continuing to buckle, while online distribution remains in its infancy. Film critics, who’ve historically championed new work and alerted their readers to it, are an increasingly endangered species. A common refrain, repeated so often it becomes tiresome, is that the best work now being done is in television, in dramas such as Breaking Bad and Mad Men.

Earlier this autumn, adding to the sense of gloom in the independent film sector, James Schamus, the writer of many of Ang Lee’s movies and a patron of British filmmakers including Mike Leigh, Joe Wright and Roger Michell, was ousted from his job as the boss of Focus Features, Universal’s “specialty” label. To many, this was confirmation that Hollywood had lost patience with director-driven art-house fare. Who needs Brokeback Mountain (one of Scahmus’ most famous films) when you can have The Avengers and other franchises, seems to be the philosophy. Who needs British films either? If Focus Features is now to be taken in a more obviously commercial direction, it is unlikely its new bosses will want to support independent British filmmakers.

Barker, though, continues to argue that there are strong business as well as cultural reasons for supporting auteurs. His strategy hasn’t changed since he and his partner Tom Barnard (then at United Artists) released Truffaut’s The Last Metro (1980.) Directors are always given final cut. Budgets are kept down. The aim is to make films with artistic integrity that will last, not simply to go after the opening weekend audience. Initial numbers may not be spectacular but, Barker suggested, significant profits can still be “eked out” in the long run.

Since the break up of the UK Film Council in 2011, there has been a subtle but significant change in the approach to film funding in the UK, which is now closer to that taken by Barker at Sony Pictures Classics. Most importantly, there is more trust in the film-makers.

During the early days of the Film Council, the emphasis was on supporting producers rather than nurturing auteurs. The rhetoric from senior Film Council figures was about creating “large companies with clout and market capitalisation who are in there for the long term” and of being “more industry friendly and much more commercially focused”. The Film Council Chief Executive John Woodward told one newspaper that the Film Council would help finance “popular films that the British public will go and see in the multiplexes on Friday night”. The Film Council’s then chairman Alan Parker made a controversial speech in which he talked of “distribution pull, not production push”.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

The main goal was to gain access to international distribution for British films. The actual films to be fed into the distribution system seemed almost like an afterthought. Script development executives, shaping new projects into pre-ordained shapes, held more sway than the directors with strong personal visions. It was little wonder that, in such a climate, auteurs such as Terence Davies felt so neglected. The British were essentially trying to make mainstream, studio-style movies.

In a digital era in which anyone can upload a movie, access to distribution is no longer the issue. As the co-chairman of Working Title Tim Bevan pointed out in a Creative Content Summit during last year’s London Olympics, “distribution was absolutely king 25 years ago, now the balance has shifted. Access to distribution is easy, it’s the access to creative quality, or even to financing creative quality, that’s rare.”

The Brits have largely stopped making gangster movies and derivative comedies in a desperate, and usually forlorn, bid to find an audience. There is at last space once again for filmmakers with strong and idiosyncratic personal visions. That’s why 2013 can fairly be described as a vintage year for British cinema in spite of the absence of blockbuster successes. Like Sony Pictures Classics, the most important British funders, the BFI, BBC Films and Film4, are now all prepared to back the talent even when it veers off in the most oblique directions.

There was nothing obviously commercial about many of the movies from British directors that screened in the LFF. Fiennes’s The Invisible Woman, about the secret relationship between Charles Dickens and Nelly Ternan, isn’t the typical British period drama. It’s a brooding, hermetic film about a love affair that was kept secret at all costs. Steven Knight’s Locke is set entirely inside one car, with only one character (played by Tom Hardy), making and receiving phone calls. 12 Years a Slave is a gruelling drama about slavery that left many audience members reeling. A Selfish Giant is a grim but beautifully made drama that combines social realism and fairy tale elements to heartbreaking effect.

We are still missing Harry Potter, which for many years was the British film industry’s equivalent to North Sea oil (even though the films were made for Warner Bros). Nonetheless, in the range and adventurousness of the films made by British directors, 2013 has surely been a banner year. For now at least, there is a sense that we are ready to invest in the talent. That, Barker reminded us as he reminisced about United Artists before the calamity of Heaven’s Gate, was what made UA work – and is likely to prove good business in the long run too.

“They (UA) really backed people like Stanley Kramer, Stanley Kubrick and Billy Wilder … they tended to continue with those filmmakers and they had a theory that there was nothing totally reliable in the film business except the choice of a talent. If they [the directors] made a movie that didn’t work, you’d just keep making movies with them. Over time, it’s that talent which will be more reliable as a business barometer than almost anything else!”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks