‘The transcripts were absolutely unbelievable’: The dramatisation of Vardy v Rooney and why TV just loves WAGs

Katie Rosseinsky explores the cultural sweet spot where money, class, football and the tabloids meet

At 10.29am on 9 October 2019, Coleen Rooney posted a statement on Twitter. It was crafted with all the narrative tension and dramatic flair of a classic whodunnit. “For a few years now,” it read, a follower on her private Instagram account had been sharing details of her posts with The Sun newspaper. After puzzling over the case for “a long time”, she developed a hunch as to “who it could be” – to prove it, she constructed a simple but dazzlingly effective social media sting operation.

Rooney, the wife of former England captain Wayne, blocked all but one account from viewing her Instagram Stories, then cooked up a handful of fake news titbits: one claimed she was considering flying to Mexico to investigate gender selection treatment, another hinted at a return to TV and a third bemoaned a (fictional) flood at the Rooneys’ new home. These stories made their way into the pages of The Sun – and Coleen “saved and screenshotted all the original stories, which clearly show[ed] just one person viewed them”. Then came the devastating reveal, the suspense soaring with every additional dot in her elongated ellipsis: “It’s………. Rebekah Vardy’s account.”

Soon, Rooney’s detective work was everywhere, from Twitter memes (including the first coinage of “Wagatha Christie”, which would soon become tabloid shorthand for this war of WAGs) to the pages of the broadsheets. Vardy, married to Leicester City star Jamie, would deny the accusations vehemently and indelibly. “Arguing with Coleen is like arguing with a pigeon,” she told the Daily Mail soon after. “You can tell it that you are right and it is wrong but it’s still going to s*** in your hair.”

Vardy launched a high court libel case, and details began to emerge: a phone belonging to her agent Caroline Watt mysteriously ended up at the bottom of the North Sea. Over the course of seven days in May, the two women went head-to-head in room 13 of the Royal Courts of Justice; two months later, Mrs Justice Steyn ruled in Rooney’s favour.

Inevitably, the “Wagatha” saga is now the subject of a TV show, Vardy v Rooney: A Courtroom Drama, which was dramatised from actual court transcripts, and will air on Channel 4 later this week. “No one could watch this [case] – everyone was just getting this kind of live stream from the journalists who were in the courtroom,” executive producer Tom Popay explains. “It was all so sensational, so we were like, ‘Well, what kind of new stuff would we learn if we fully recreated the trial?’ We sent off for the transcripts and when they came… they were absolutely unbelievable. We realised that all the tweets and reports from the trial had just scratched the surface.”

Our obsession with WAGs might seem enjoyably trivial on the surface, yet delve a little deeper and you soon start to unravel a nexus of cultural hot topics: football, yes, but also tabloid media, money and, crucially, class. No wonder TV keeps returning to these women.

To get to the heart of this very British phenomenon, we need to rewind three decades. In 1992, the FA launched the Premier League, the highest level of the men’s professional game contested by the top 20 clubs in English football, and money flooded into the sport through lucrative media contracts. The average weekly wage of a Premier League player in 1993 was £2,246, according to the website Sporting Intelligence; by 1998, at the end of Sky TV’s first five-year deal with the Premier League, it had more than tripled to £7,136. By 2019, it stood at around £61,000 a week, a number that had risen more than £10,000 in the two preceding years (according to Statistica, players at Rooney’s old club now enjoy the highest average salaries in the Premier League, receiving an average of £7.19m annually).

Footballers and their partners became synonymous with a lavish, flashy lifestyle, in tandem with “the rise of celebrity magazines”, notes Helen Wood, professor of media and cultural studies at Lancaster University. The likes of OK! (launched in 1993) and Heat (which followed in 1999) devoted their pages to “young women with spending power”, at a time when “girl power” rhetoric had major cultural currency, celebrating “women who want to have more, [and] do it their way”.

Many of the early WAGs – such as Louise Redknapp, Dani Behr and Ulrika Jonsson, high-profile partners of Jamie Redknapp, Ryan Giggs and Stan Collymore– were famous in their own right. They became “very powerful in media terms”, Wood explains, “because they’re spectacular, they look good, they’re in all the right places” – and were very good at spending money. “It was a power through consumption, rather than power that can make any social or political change,” she adds.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

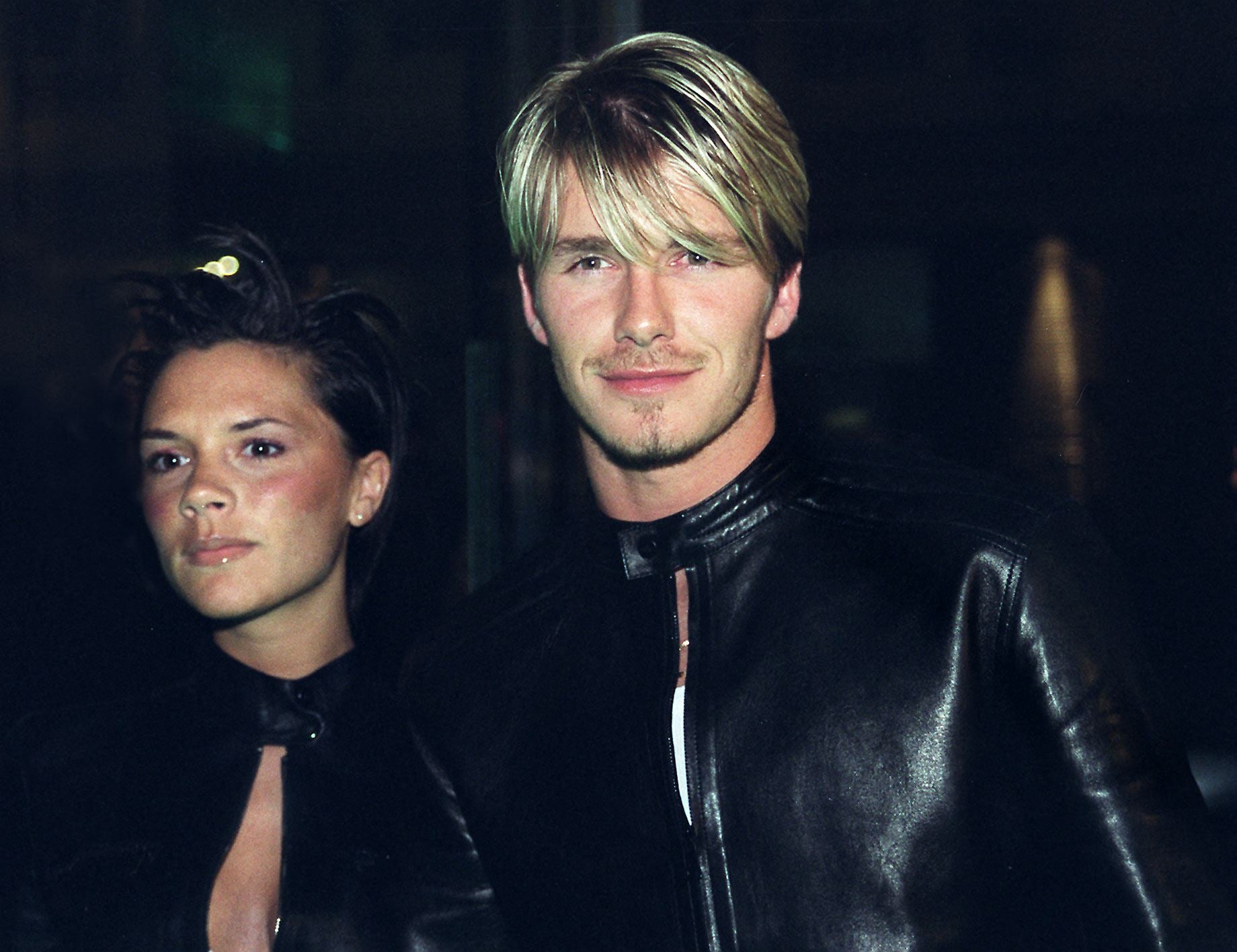

The biggest proponents of “girl power”, of course, were the Spice Girls – and in 1999, Victoria Adams, aka Posh Spice, supercharged the WAG game when she married David Beckham. The couple received a rumoured £1m from OK! for their wedding pictures (including an unforgettable shot of the de facto king and queen of UK showbiz sitting on matching velvet thrones).

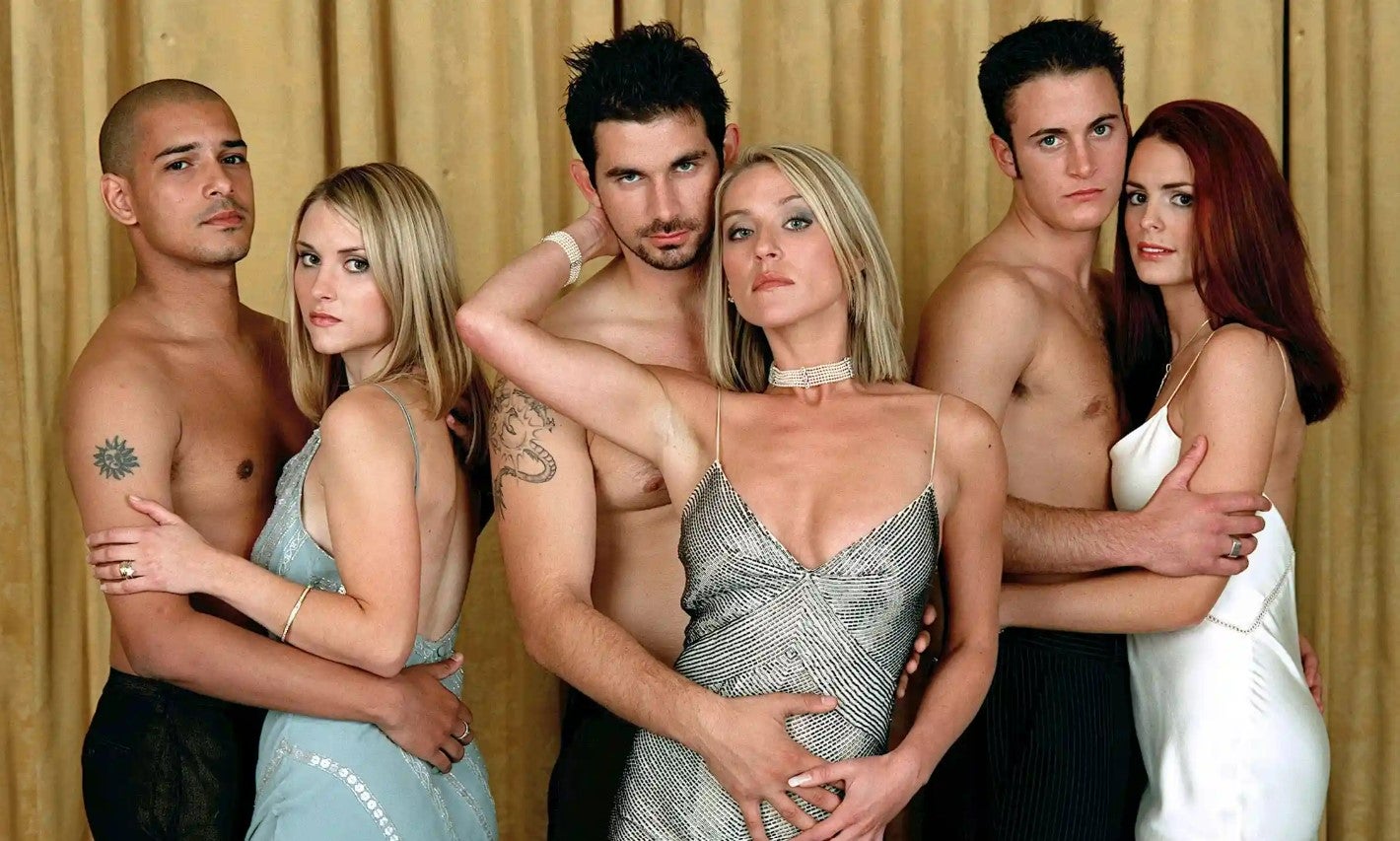

Against this backdrop, TV execs scrambled for ways to cash in on the phenomenon. Sky One launched Dream Team, a soapy drama based around fictional Premier League club Harchester United in 1997, but it was Footballers’ Wives, which debuted in 2002, that would really capture the public’s imagination. Focusing on the off-pitch antics of the WAGs of another fictional club, Earls Park, the ITV series had a simple but effective premise: it was all about “young people with loads of money and very little sense, and those scrapes they can then get into on a very dramatic scale”, co-creator Maureen Chadwick says.

The first season revolved around three couples, each rooted in different tabloid archetypes. There was golden boy Kyle Pascoe (Gary Lucy) and his glamour model fiancée Chardonnay (Susie Amy); new signing Ian Walmsley (Nathan Constance) and his childhood sweetheart Donna (Katherine Monaghan); and captain Jason Turner (Cristian Solimeno) and his Machiavellian wife Tanya (Zöe Lucker), whose increasingly melodramatic schemes to keep her husband in a job (and herself in a marriage) were fuelled by a heady cocktail of pre-match G&Ts, cocaine and immaculately applied fake tan.

Footballers’ Wives, Chadwick explains, was always intended as “satire”, but “some snooty male journalists” couldn’t get their heads around the possibility of two women deliberately writing a witty series set in the world of sport. “[They] thought that Anne [McManus, the show’s co-creator] and I didn’t know that it was funny,” she recalls. “They thought that we were accidentally funny.” The show’s tone may have been cartoonish, but it also managed to capture what composer Kath Gotts, who has turned the larger-than-life events of the drama’s first season into stage show Footballers’ Wives: The Musical with Chadwick, describes as “the precariousness of this world with loads of money and instant glamour”.

“Footballers have got a career until they break an ankle or something,” she says. “There’s a kind of ‘on edge-ness’ about that, and also for the partners, the wives and girlfriends.” They, like Tanya, constantly grapple with the threat of being replaced by a younger, prettier model. “You have that tension in a relationship, the power balance of ‘we’re a team until maybe, suddenly, we’re not’.”

Some critics might not have immediately got Footballers’ Wives, but the media eventually backed it in a big way. In a meta twist, OK! “covered” the christening of Kyle and Chardonnay’s baby “on the front page” in January 2003, and “treated it as real life”, Chadwick says. The Guardian, meanwhile, ran a piece by Germaine Greer, who praised how the show put “the female gaze behind the camera – we saw all the footballers naked… that scrutiny of the men’s bodies is definitely something we strove to achieve, so that it wasn’t just looking at the women’s enhanced tits or anything like that”.

The viewing public lapped it all up: by the time season two came around, Footballers’ Wives drew in the same audience share as a David Attenborough nature documentary airing concurrently on BBC One. “Didn’t people write in and ask for the wedding vows of Kyle and Chardonnay?” Gotts asks Chadwick during our Zoom call (that unforgettable episode also featured a Katie Price-alike horse-drawn carriage and a small boy serenading the newlyweds with “Walking in the Air” from The Snowman). “Yes, and baby girls were christened Chardonnay,” Chadwick recalls (65 girls were registered as Chardonay or Chardonnay in the 12 months following the first season, The Independent reported in 2003).

As Footballers’ Wives went on, its plots got wilder and wilder. Tanya hired a lookalike to do community service after being hit with a drugs charge; there was a paternity row involving a fake-tanned baby; and Joan Collins made a cameo. But by the time ITV blew the whistle after five seasons in 2006, it couldn’t quite compete with the real-life WAG antics happening off-screen.

That year, of course, was when WAGdom reached its apex at the World Cup in the sleepy German spa town of Baden-Baden. Faced with a photogenic, designer label-loving squad of WAGs, led by captain’s wife Beckham, the tabloid media went into overdrive. The papers painstakingly reported every update, as the women danced on the tables at Garibaldi’s Bar, shopped so much that the Spanish press branded them “hooligans with Visas”, and brought along two dedicated spray tanning assistants (per one Daily Mail report) for the ride.

The not-so-subtle subtext to all this? The WAGs were too loud, wore too many labels, and flashed too much cash, and their excesses took on a moral dimension. “Footballers tend to be working-class kids done good, and the women that they tend to marry are also from those kinds of backgrounds,” Wood notes. “When working-class people get money, they’re always judged for not spending it appropriately… Any kind of ostentatious show of wealth offends that middle-class sensibility.”

When Sven-Göran Eriksson’s England team crashed out of the 2006 World Cup in the quarter-finals, the WAGs were blamed for their poor performance, slammed as distractions. “The FA tried to quash [them], because they hated the fact that [focus] was being pulled away from the men’s team, which is pretty damn sexist, especially considering how bad the men’s team were,” says Popay. Four years later, new manager Fabio Capello curtailed the wives’ visits, limiting them to one after each game.

It was just the continuation of the FA’s old-fashioned attitudes to players’ wives at major tournaments: in ITV’s next WAG dramatisation, 2017’s sweet, far-from salacious Tina and Bobby, we see Tina Moore (Michelle Keegan) and her fellow Sixties WAGs barred from celebrating the 1966 World Cup win with their husbands at the official banquet by an FA official (which really happened).

In the late Noughties, WAGs moved on from fictional dramas and began to take over reality TV. Rooney hosted Coleen’s Real Women, where she doubled down on her likeable girl-next-door status to talent-spot “real” beauties, who’d vie to land various modelling gigs. Girls Aloud’s Cheryl, meanwhile, became the nation’s sweetheart as a judge on The X Factor in 2008, in the wake of husband Ashley Cole’s well-publicised cheating scandal (her final season in 2010 coincided with the show’s highest-ever viewing figures).

As the fortunes of the men’s team languished, the WAGs also seemed to occupy less space in our cultural consciousness – until “Wagatha Christie” reignited our dormant interest. In the summer of 2020, shortly after news broke that Vardy would be taking Rooney to the High Court, Apple TV+ comedy Ted Lasso premiered, introducing viewers to another made-up London team, AFC Richmond, and ushering in a new, wholesome era for WAGs on TV.

So far, the show’s star Juno Temple has earned two Emmy nominations for her portrayal of Keeley Jones, a glamour model turned WAG turned social media marketing supremo. The sunny, emotionally intelligent antithesis to Tanya Turner, she spends much of season one picking up the pieces from her toxic relationship with Jamie Tartt (played by Phil Dunster as a less endearing Jack Grealish), eventually coaxing grumpy captain Roy Kent (Brett Goldstein) out of his shell.

Though the show’s writers initially pit her against Richmond’s female owner Rebecca (Hannah Waddington), the pair’s friendship becomes the heart of the show, in a refreshing (and yes, very earnest) spin on catfight narratives. Her social media expertise, too, positions her as a savvy strategist who is in control of her own – and eventually, the club’s – image.

The footballer’s wife as branding expert is far from a new phenomenon. Tina and Bobby shows Keegan’s character selling a perfectly packaged home life, cradling a baby while cooking a roast dinner in a Bisto advert – just like the real Tina Moore did. The social media era, though, has “accelerated” the way that WAGs “are playing a system they’ve been thrown into”, making money out of domesticity by “thinking about where to be seen [and] what brands to associate themselves with”, Wood notes.

There’s debate, she adds, over whether anybody “sees that [work] as having any kind of value”, but it is work all the same: the work of curating “the sense of a life [that’s] really carefully put together with managers and brand agents and sponsorship”. If Ted Lasso’s portrait of how Keeley plays the media is pretty sanitised, the “Wagatha” affair exploded the facade, inviting the general public to gawp at the WAGs’ symbiotic relationship with the press.

In Vardy v Rooney, the real texts sent by Vardy (Natalia Tena) to her agent about passing stories to the press “pop up and invade the space” of the courtroom, “like a message would on your phone”, explains producer Catherine Donohoe. The “quid pro quo” of sharing gossip to “stay relevant” is, Popay adds, “at the heart of the case” – so is the way the media built up Vardy, bolstering her career through her Sun column and her I’m A Celebrity… appearance, then dropping her when the tide turned.

“In many ways, the media helped make both of these women, but especially Vardy,” Popay says. “She came from really tough beginnings, and she saw her opportunity and she took it. The media really helped shape her, and then they were obviously at the heart of what she had been accused of. And when she takes it to trial… they’re there on the front row where the jury is supposed to sit, basically sitting in judgement on her.”

What sustains our fascination with WAG stories, fictional and real? “A footballer’s wife is kind of achievable,” Wood notes – it’s “a quick route to money” that seems fairly attainable, unlike, say, Hollywood stardom. But the very flukiness of their wealth and success is also the reason they are the targets of critique. Our society doesn’t lay out many paths for working-class women to succeed, but it certainly loves to slag them off for rising above their station: wealthy WAGs might not need our sympathy, but do they really deserve pure vitriol? Vardy v Rooney takes a refreshingly dispassionate approach to the Wagatha court case. “The biggest thing we really didn’t want to do was denigrate anybody,” Popay stresses. “We knew that they both had very different, very compelling reasons to be in court doing this.”

What riles us about these women, Wood says, is “the same thing [we don’t like about] reality celebrities, which is that they’re celebrities for living their own life. They’ve got something for nothing initially – [we] don’t like that there’s a route to social mobility without having any skill or talent… and this doesn’t fit with ideas about a meritocracy.” There’s certainly an element of schadenfreude at play when we see these women’s lives go wrong on screen – “There’s a sense of undeserved riches, in some way, so therefore the schadenfreude is all the more juicy, isn’t it?” Gotts says.

The tabloid media’s complex attitude to working-class women seems unlikely to unknot itself any time soon, and neither does our obsession with footballers’ wives: just look at recent headlines about the cruise ship chartered by the current WAGs during the Qatar World Cup. “People called [“Wagatha Christie”] the last act of the WAGs, and maybe I just don’t want it to be, but I just don’t think that’s true,” Popay says. After Rooney reportedly secured a multi-million pound deal with Disney+ to tell her side of the story in a “Wagatha” documentary, it certainly doesn’t look like it – indeed, it seems we’ve barely even got started on extra time.

‘Vardy v Rooney: A Courtroom Drama’ is on Channel 4 on 21 December at 9pm. ‘Footballers’ Wives: The Musical’ Studio Cast Recording is on Spotify now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks