TV review, Hospital (BBC2): Documentary captures the realities of the NHS

Plus: The Split (BBC1)

Sometimes documentaries such as Hospital are disparaged as elongated undeclared political adverts – appeals for cash in effect – made by one much-loved public institution (the BBC) on behalf of another (the NHS). Thus, programme makers in search of heart-breaking stories and rare access to terrified patients and busy clinicians are served those things up by the relevant NHS trust management in return for a none-too-subtle case being made for more money. “Shroud waving” I believe it’s called.

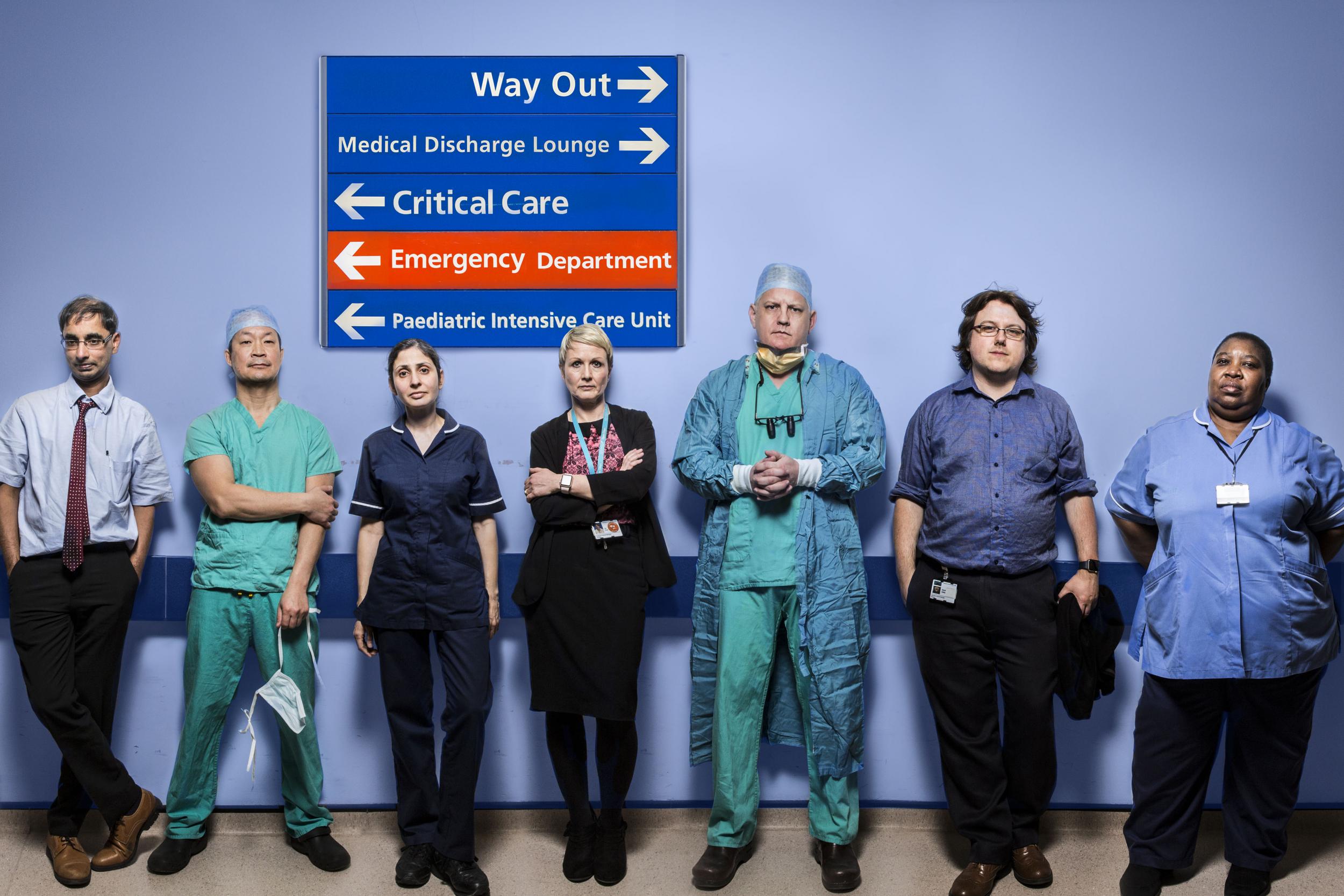

This is unfair, and certainly so in the case of Hospital, the BBC’s latest run around the wards, this time at the Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, focusing in particular on the hard-pressed 58-bed critical care ward.

For a start, it does no harm at all to be informed, or, for those of us with recent experience of NHS care, reminded that the NHS is under increasing pressure, and to see the graphic corroborating evidence at close hand. When one clinician tells us they can now save the lives of patients they could not have had a hope of keeping going five or 10 years ago, we believe them. We watch as a 90-year-old involved in a car accident with severe injuries is treated as sympathetically and urgently as any teenager with their best years ahead of them. One day the luckiest amongst us will reach that sort of vintage and be thankful for that degree of solicitude.

We learnt all about the realities of what’s called “rationing by clinical need” (as opposed to how much you can pay). Thus we were, implicitly, asked to choose between which of six patients should be given the one critical care bed available for post-operative care. So the doctors are being asked to choose between a severe spinal disc hernia, two cancer cases, a bowel obstruction, a liver re-sectioning and an 18-year-old with a spinal curvature. Even if I understood the medicine involved I’d be hard pressed to make such a decision. Things, though, can be ameliorated if the teams on the various wards are able to move patients through the system more quickly, making the best use of the beds available, and sending the less demanding patients to less stressed wards or even other hospitals. It might feel a bit rum to be shuttled from one location to another, but it is in fact simply an expression of the extreme efficiency the NHS operates under, as impressive as anything that, say, Amazon manages. Orthopaedic wards seem to me like human versions of a Kwik Fit garage, new hips and knees being fitted with the same speed as the fitters can slot in a new exhaust or tyre. Thus, often as not – as the professionals know full well – the art of NHS patient care is as much a matter of logistics as it is of drugs and surgery.

I did hear one medic grumble about systems elsewhere in the world being better than the NHS, while others left the obvious lack of resources simply hanging in the air, like the whiff of a used bed pan, from which the audience could draw its own diagnostic conclusions.

The conclusion I drew, however, is not that the NHS is “failing” as both critics on the left and the right claim (though the ones on the right use horror stories to try and destroy its reputation) – but rather how well it is doing. Satisfaction ratings with the NHS remain astonishingly high, and, I sense, the public accepts that, whatever the shortcomings, the quality of professionalism within the NHS makes it an institution worth defending. If you or a friend or family member have had some treatment recently I invite you to ponder how much it would cost you in cold hard cash if you had to pay for it yourself, or the price of the insurance premiums (if you could get the illness insured) you’d have to pay.

As the NHS approaches yet another milestone – turning 70 in July – it is in fact in remarkably good health, despite the many stresses it is under. It needs, in truth, no adverts for the good it does each patient and the nation as a whole. There’s certainly an argument to be had about priorities, about funding and about management and “privatisation”; but there is, thankfully, no argument about keeping it, despite the efforts of certain newspaper groups. Like I say, and unlike those newspaper groups, the NHS is much-loved and is an unarguable force for good.

The trouble with The Split, I find, is that so many of the characters are so unlikeable, or leastways morally ambiguous, and not simply because they’re divorce lawyers – it’s because they are such randy divorce lawyers. Not just randy, but seriously contemplating – or actually engaged upon – philandering, with their colleagues, their exes, their exes’ siblings, their exes’ colleagues, their exes’ colleagues’ siblings’ colleagues, their clients, their clients’ colleagues…So it was quite a relief to be diverted by a more conventional sort of legal barney, that being over a pre-nup between a randy philandering premiership footballer (Thierry Mabonga) and a randy glamour model (Chanel Cresswell), who just appeared to be philandering. As Henry Kissinger once said of the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s: “It’s a pity both sides can’t lose.” Except in family law both sides usually do lose. Anyway, and in no particular order, Anthony Head, Meera Syal, Nicola Walker, Stephen Mangan, Deborah Findlay and the whole crew work like one big happy family to make this whole improbable legal lark roll along surprisingly well. Better together, as they say.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks