Last Night's TV - When God Spoke English: the Making of the King James Bible, BBC4; Royal Upstairs Downstairs, BBC2; The Story of Variety with Michael Grade,BBC4

The power and the crowning glory

King James VI of Scotland and I of England was a monarch four centuries ahead of his time. Take his celebrated "A Counterblaste to Tobacco", an anti-smoking tirade that for years seemed rather over the top even to those of us who have never drawn on an unfiltered Pall Mall, but has now more or less passed into the statute books. The smokers huddled together on pavements outside offices, or in pub car parks, know all too well that society has finally endorsed the view of old King James that theirs is "a custom loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, dangerous to the lungs, and in the black stinking fume thereof nearest resembling the horrible stygian smoke of the pit that is bottomless". Government health warnings were so much more lyrical in 1604.

That was also the year in which James convened the Hampton Court Conference, gathering together mainstream Anglicans and crosspatch Puritans in a laudable attempt to find some liturgical common ground, while at the same time bolstering his own authority. He was a smart cookie, but not for nothing was he known as "the wisest fool in Christendom". It was James who unwittingly prepared much of the ground for the civil war that would tear the kingdom apart less than 20 years after his death and end in the execution of his son, Charles I.

You must excuse me these musings on a long-dead king. It's not often one gets the chance in a TV column to breathe life back into a history degree obtained more than a quarter of a century ago, which is why I watched When God Spoke English: the Making of the King James Bible with such interest.

The programme was presented by the impressively gangly Adam Nicolson, who is himself something of an English institution, being the Sissinghurst-raised grandson of Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson. Indeed, he is nothing less than the fifth Baron Carnock, and yet eschews the title, which would have mystified the royal court 400 years ago, for James I quickly cottoned on to the sale of baronetcies as an easy way to make money. In that sense, too, James was ahead of his time: dishing out peerages in return for handsome political donations happens in Armani suits as much as it ever did in doublet and hose.

Anyway, Nicolson clearly enjoyed making this documentary, which made it easier to enjoy watching it. His script occasionally veered towards the fanciful, as when he described the fleeing of the English separatists across the North Sea to Holland. "You can still feel some of that tension on the bleak muddy banks of the Humber estuary," he said, striding along said bleak, muddy banks in his wellies, looking anything but tense. Nevertheless, hats off to him for bringing such colour to what in different hands could have seemed decidedly monochrome.

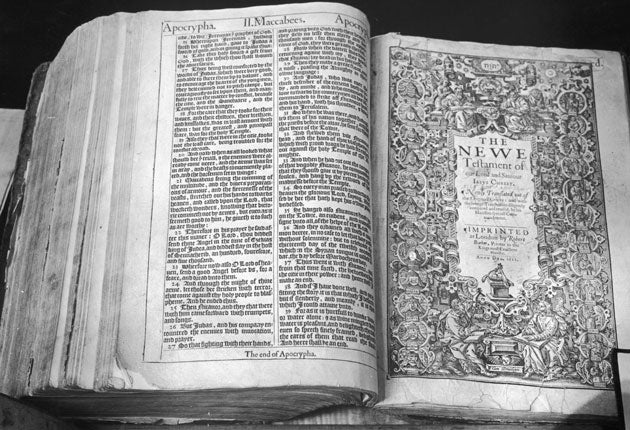

The Hampton Court Conference of 1604 never really achieved what James hoped it would, and yet from it came the Authorised Version of the Bible that Nicolson not very objectively, but not unreasonably either, considers to be "perhaps the greatest book ever written in English". Pieced together by 50 translators, it was eventually published in 1611, and Nicolson presented a moving example of how the 77th psalm, "a poem written in the Near East in the Bronze Age, translated 400 years ago", has modern relevance in the particular comfort it has given a Hebridean fisherman he knows, whose son died in his early twenties.

Of course, there were Bibles in English before the 1611 version, notably William Tyndale's effort a century or so earlier, from which "bald as a coot", "rise and shine" and "eat, drink and be merry" all passed into common usage. But it wasn't an enduring masterpiece like the Bible commissioned by King James I, and for all the old boy's foibles, which incidentally included a relentless enthusiasm for pederasty, I'm rather pleased that his name lives on in connection with one of the great achievements of English literature.

And so to a monarch whose name lives on in myriad ways, and whose visits to what we now call stately homes are celebrated in no fewer than 20 parts in Royal Upstairs Downstairs. This is presented by Tim Wonnacott and Rosemary Shrager, one a TV antiques expert, the other a TV chef, who both seemed here to be trying a little bit too hard to be "characters". But then perhaps they are "characters". Being familiar with neither of them, I wouldn't know.

Whatever, their brief is to explain the impact that Queen Victoria's arrival had on big houses, both above and below stairs. They started with Chatsworth, which Victoria visited in 1832, when she was merely a 13-year-old princess, though evidently already old enough to know her own mind. Her host, the sixth Duke of Devonshire, laid on a lavish welcome banquet, but since she'd only arrived half an hour before dinner, she decided to eat in her room.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Heaven knows how often the present royals have wanted to do the same thing, and make an imperious withdrawal from proceedings. Every Royal Variety Performance, I shouldn't wonder, though the engrossing concluding part of The Story of Variety with Michael Grade had a clip of Prince Charles at the Palladium looking as if he was genuinely enjoying himself. Probably because it was nearly time to go home.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments