Thank you, come again? Hank Azaria and ‘the problem with Apu’

The multivoiced actor talks to Dave Itzkoff about how his perception of the Kwik-E-Mart shopkeeper has changed over time – along with everyone else’s

In the three decades that he has been a voice actor on The Simpsons, Hank Azaria has played dozens of Springfield’s absurd denizens on that long-running animated Fox comedy, including the surly bartender Moe, the inept lawman Chief Wiggum and the adenoidal bookworm Professor Frink.

But in recent years, Azaria has become irrevocably associated with one Simpsons character in particular: Apu, the obliging Indian immigrant and proprietor of the town’s Kwik-E-Mart convenience store.

Azaria has played the character since his first appearance in 1990, but he and the show have faced increasing condemnation from audience members who feel that Apu is a bigoted caricature.

To these critics, many of whom are of Indian descent, Apu is a servile stereotype. As voiced by Azaria, who is white, Apu’s ethnic accent and his catchphrase, “Thank you! Come again!”, have become grating slurs.

Azaria now says that he will no longer play Apu on The Simpsons. It is a choice he says he made for himself after a years long process of examining his own feelings and listening to others who explained how they had been hurt by Apu, who was for years the only depiction of an Indian person they saw on TV.

“Once I realised that that was the way this character was thought of, I just didn’t want to participate in it anymore,” Azaria tells me. “It just didn’t feel right.”

Even after Azaria reached this decision, which he first disclosed to the blog /Film, questions remain about how Apu will be handled going forward on The Simpsons, whose producers have been hesitant to address the controversy surrounding the character.

In a statement, the executive producers of The Simpsons said: “We respect Hank’s journey in regard to Apu. We have granted his wish to no longer voice the character.”

However, the producers did not indicate whether the character would continue to appear on the show, as voiced by another actor. In their statement, they said: “Apu is beloved worldwide. We love him too. Stay tuned.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

While the fate of Apu is out of Azaria’s hands, the actor says he found value in engaging with viewers whose arguments he was initially reluctant to hear and in coming to understand that resistance to hearing them.

His experience, he says, could be instructive at a time when representation remains a fraught topic in popular culture and when creators and performers fear drastic repercussions if their work is deemed out-of-step with contemporary standards.

“What happened with this character is a window into an important issue,” Azaria says. “It’s a good way to start the conversation. I can be accountable and try to make up for it as best I can.”

In his acting career, the 55-year-old has had prominent roles in various live-action films (The Birdcage), TV dramas (Ray Donovan) and comedies (including Friends, Mad About You and his IFC series Brockmire, which begins its final season on 18 March).

He has also worked on The Simpsons since its first season, which included the episode that introduced Apu as a fussy shopkeeper oblivious to the thieving teens in his store. Azaria says he based the character’s voice on clerks he had heard growing up in New York, who tended to be Indian and Pakistani.

He says he had also drawn inspiration from the 1968 Blake Edwards comedy The Party, in which Peter Sellers wore brownface to play a bumbling Indian actor. Azaria says that at the time, he had no idea so many viewers had come to regard Sellers’ performance as racist.

“That represents a real blind spot I had,” Azaria says with some disappointment. “There I am, joyfully basing a character on what was already considered quite upsetting.”

Over the next 25 years, Apu appeared frequently on The Simpsons, sometimes in episodes that mocked xenophobia and anti-immigrant attitudes in America, and Azaria won multiple Emmy Awards for his work on the show. But the character and his performance came under increased scrutiny.

In a 2012 performance on the FX series Totally Biased with W. Kamau Bell, comedian Hari Kondabolu celebrated the growing number of Indian Americans on television while singling out Azaria for an obsolete portrayal.

“There’s now enough Indian people where I don’t need to like you just because you’re Indian,” Kondabolu says in the segment. “Because growing up, I had no choice but to like this: Apu, a cartoon character voiced by Hank Azaria, a white guy. A white guy doing an impression of a white guy making fun of my father.”

Azaria says he saw Kondabolu’s routine online but was too defensive then to take in its message. “My first reaction was to bristle,” Azaria says. Recalling his feelings at the time, he says he had justified Apu to himself by noting that many Simpsons characters were based on stereotypes. “We make fun of everyone,” Azaria says. “Don’t tell me how to be funny.”

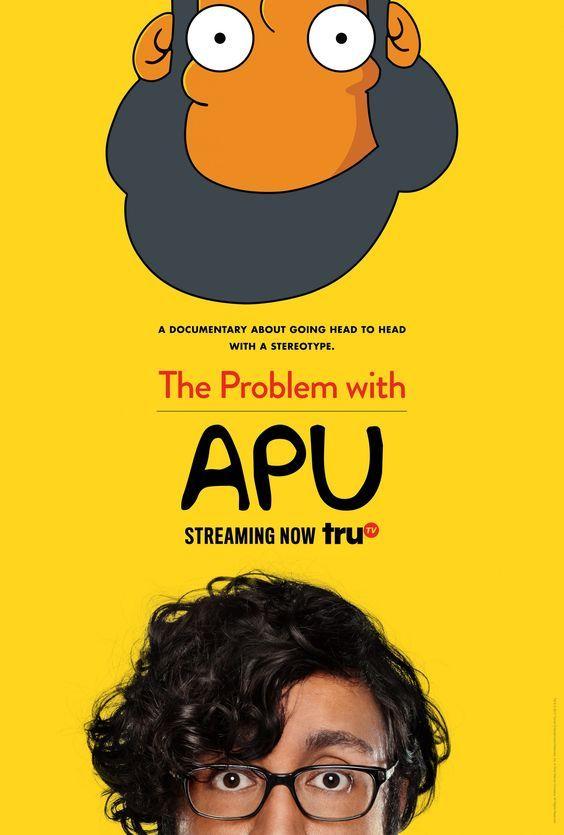

Kondabolu later wrote and starred in a documentary, The Problem with Apu, in which he spoke to other Indian American actors and performers who discussed how the character had become emblematic of the biases and marginalisation they face in the entertainment industry.

Kondabolu also sought Azaria for an on-camera interview but was unable to secure his participation. He says the purpose of his film had never been to target Azaria or to disrupt his career, but to illustrate an issue of representation for viewers.

“The goal was for all these other people who saw it to have critical questions – to force them to think about things in a way that might have made them uncomfortable, and it was an accessible way to think about it,” Kondabolu says.

He adds: “At no point did I want them to cancel The Simpsons or get rid of the character.”

By the time The Problem with Apu was shown on truTV in 2017, Azaria was well aware of the debate surrounding Apu but unsure of what he should do. “I didn’t want to knee-jerk drop it if I didn’t feel that was right, nor did I want to stubbornly keep doing it if that wasn’t right,” he says.

Azaria says he continued to read articles and essays about representation, and he attended seminars about racism and social consciousness.

As a white Jewish man, Azaria asked himself, if there were a prominent character in popular culture that mocked those same traits, how would he feel about it?

That alone might not bother him, he says. “But then I started thinking, if that character were the only representation of Jewish people in American culture for 20 years, which was the case with Apu, I might not love that.”

And while Azaria has played all kinds of stock characters on The Simpsons – brash Southerners, unctuous Brits, frustratingly polite Canadians – he says they were permissible in a way that Apu is not.

“There hasn’t been an outcry over these characters because people feel they’re represented,” he says. “They don’t take it so personally, nor do they feel oppressed or insulted by it.”

Azaria also sought the opinions of Indian American friends and colleagues. They included actor Utkarsh Ambudkar, with whom Azaria had worked on The Simpsons and Brockmire.

Ambudkar, who also appeared in The Problem with Apu, said that at the time he spoke to Azaria, “he was in a space where he was exploring, where he was trying to open up and take responsibility”.

“I felt a genuine dedication to growth, for himself, as a human being,” Ambudkar continued. “He wanted to get on the right side of the narrative.”

Even so, Ambudkar added: “As a south Asian, I wish that it had happened 15 years ago. I love Hank very much, but his Indian accent is garbage.”

Azaria, meanwhile, had concluded that he could not play Apu anymore. In a 2018 interview with Stephen Colbert, he said: “I’m perfectly willing and happy to step aside or help transition it into something new.”

About a year ago, Azaria informed the executive producers of The Simpsons (who include Al Jean, James L Brooks and the show’s creator, Matt Groening) that he no longer wanted the role.

“When I expressed how uncomfortable I was doing the voice of the character, they were very sympathetic and supportive,” Azaria says. “We were all in agreement.”

Kondabolu says that while he hoped The Simpsons would find a creative way to deal with Apu on the show, it was more important that Azaria had acknowledged his own role in the controversy and made a sincere effort to educate himself about it.

“Whatever happens with the character, to me, is secondary,” Kondabolu says. “I’m happy that Hank did the work that a lot of people wouldn’t have. I feel like he’s a really thoughtful person and he got the bigger picture.”

Ambudkar also says it was significant that Azaria would “step out and do what he did” even if he had no power to dictate what the show did next. “The Simpsons has become a corporation and he’s an employee of that corporation,” Ambudkar says. “I know he feels peace of mind.”

For all of the emotion and condemnation he has been exposed to, Azaria says that he remains enthusiastic about his work on The Simpsons and hopes to remain with it for as long as it is broadcast.

“I love this show,” he says. “I have tremendous pride in doing the show. And the character of Apu was done with love and pride and the best of intentions. My message is, things can be done with really good intentions and have negative consequences.”

Being asked to consider other people’s feelings and adjust for them in his work, he says, was no punishment at all. “I got called out for this,” he says. “It’s not the end of the world.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks