We’re so obsessed by Big Tech, we’ve forgotten what Britain is really good at

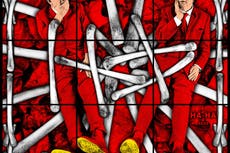

The UK’s creative industries are growing at four times the rate of the wider economy, yet continue to be treated as expendable. In an age of AI and automation, that contradiction may be our biggest mistake, says Abi Meats

Is this the hallelujah moment the creative industries have been waiting for? In the latest economic forecasts is a statistic that should make the government sit up straight. Growth in the UK’s music, video and games sector is now projected to be more than four times the 1.5 per cent GDP growth predicted for the wider economy by the Office for Budget Responsibility. Four times.

If ever there was such a shock to the system for policymakers, this should be it. Not just because it’s good news in an otherwise cautious economic outlook, but because it challenges a long-held assumption at the heart of British industrial strategy: that Big Tech is the only game in town when it comes to growth, innovation and global relevance.

For decades, people like me, working in the creative industries, have largely had to fend for themselves. Freelancing, self-funding, portfolio careers, unpaid work, personal risk – this has been the norm, not the exception. And yet, despite that lack of structural support, Britain’s creative output has remained extraordinary. Music, fashion, film, games, art and design have continued to thrive not because the system made it easy, but because creative people are resilient, inventive and resourceful by necessity.

Which raises an obvious question: imagine what the output could be if creativity were not merely tolerated, but actively supported and even revered.

For too long, creativity has been treated as a nice-to-have rather than a serious economic force. This is a huge miscalculation when you consider the eye-popping sums involved when it comes to what they are worth to the UK economy – £8bn for the music industry and £32bn and counting for fashion. Governments of all colours have talked up “world-leading” creative industries while quietly starving them of support, and nowhere is this more visible than in schools.

Over the past decade, arts education has suffered badly amid an obsession with STEM subjects, driven by the false idea that creativity and technical skills exist in competition. The narrative has been framed as a zero-sum game: if you prioritise coding, maths and engineering, the arts must inevitably lose out. But this is a profound misunderstanding of how innovation actually works.

Creativity is not the opposite of science or technology, it is the engine that powers them. The ability to think laterally, imagine alternatives, tell stories, design systems and question assumptions is what turns technical capability into meaningful progress. Some of the most successful technology companies in the world understand this instinctively: design, storytelling and user experience are not add-ons, they are central to the work.

Ironically, countries like Singapore and China openly envy Britain’s creative culture. They invest heavily in arts education precisely because they understand its long-term value – not just culturally, but economically and strategically. The UK, meanwhile, seems intent on dismantling one of its greatest advantages.

Because let’s be clear: we are genuinely world-leading at this. Fashion, music, art, advertising, film, gaming – these are not fringe pursuits. They are sectors where Britain consistently punches above its weight, exporting talent, ideas and influence across the globe. Creativity is not a side dish to our economy; it is a main course.

Look, for example, at the transformative role free-to-access art colleges played in Britain in the 1960s and 1970s. Far beyond simply training painters, potters and sculptors, they were an entree to higher education for working-class students. They also powered enormous cultural, social and political change, shaping everything from pop music and fashion to graphic design, film and radical politics, which the UK became famous for.

Today, we are living in a perpetual contradiction: we celebrate British cultural success on the global stage, while systematically dismantling the pipeline that makes those successes possible.

The contribution from the creative arts has been persistently underestimated by successive governments, and that blind spot has filtered directly into policy decisions. Cuts to art classes, shrinking art school provision, and a narrowing of what is deemed “useful” education have sent a damaging signal to young people: creativity is risky, indulgent or unserious.

This was one of the driving reasons I wrote Create – a book which is both a creative manifesto and practical guide for anyone looking to pursue creative work in design, art or other creative industries.

The book exists to make visible what has too often been invisible: the sheer breadth of jobs and roles available. Too many young people – and parents, teachers and policymakers – still imagine a creative career as a lottery ticket. In reality, the sums involved show that creativity underpins thousands of skilled, sustainable, future-facing roles, many of which intersect directly with technology, innovation and new industries. And even where creativity stands alone, it stands strong.

As we move into 2026, this matters more than ever. We are entering a world saturated with AI-generated content – what many creatives now call “AI slop”. In that environment, the most valuable skills will not be speed or volume, or even perfection, but judgement, originality, taste, ethics and independent thinking. The human ability to discern what is meaningful will become a premium skill.

In other words, the future belongs to creative, independent-minded brains.

If the government is serious about growth, productivity and global relevance, this latest OBR data should be a wake-up call. Big Tech is not the only engine of the economy. Creativity is not a nostalgic analogue indulgence. It is a strategic asset hiding in plain sight.

It’s time we stopped asking the arts to justify themselves – and started backing them properly. After years in survival mode, the UK doesn’t just need creative resilience. It needs an art renaissance.

Abi Meats is a British graphic designer, creative director and author best known as the co-founder and co-director of RUDE Ltd – a London-based creative studio iamcreative.us

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks