India bids fond farewell to veteran BBC journalist and ‘voice of history’ Mark Tully

He covered some of the most pivotal moments in South Asia’s modern history

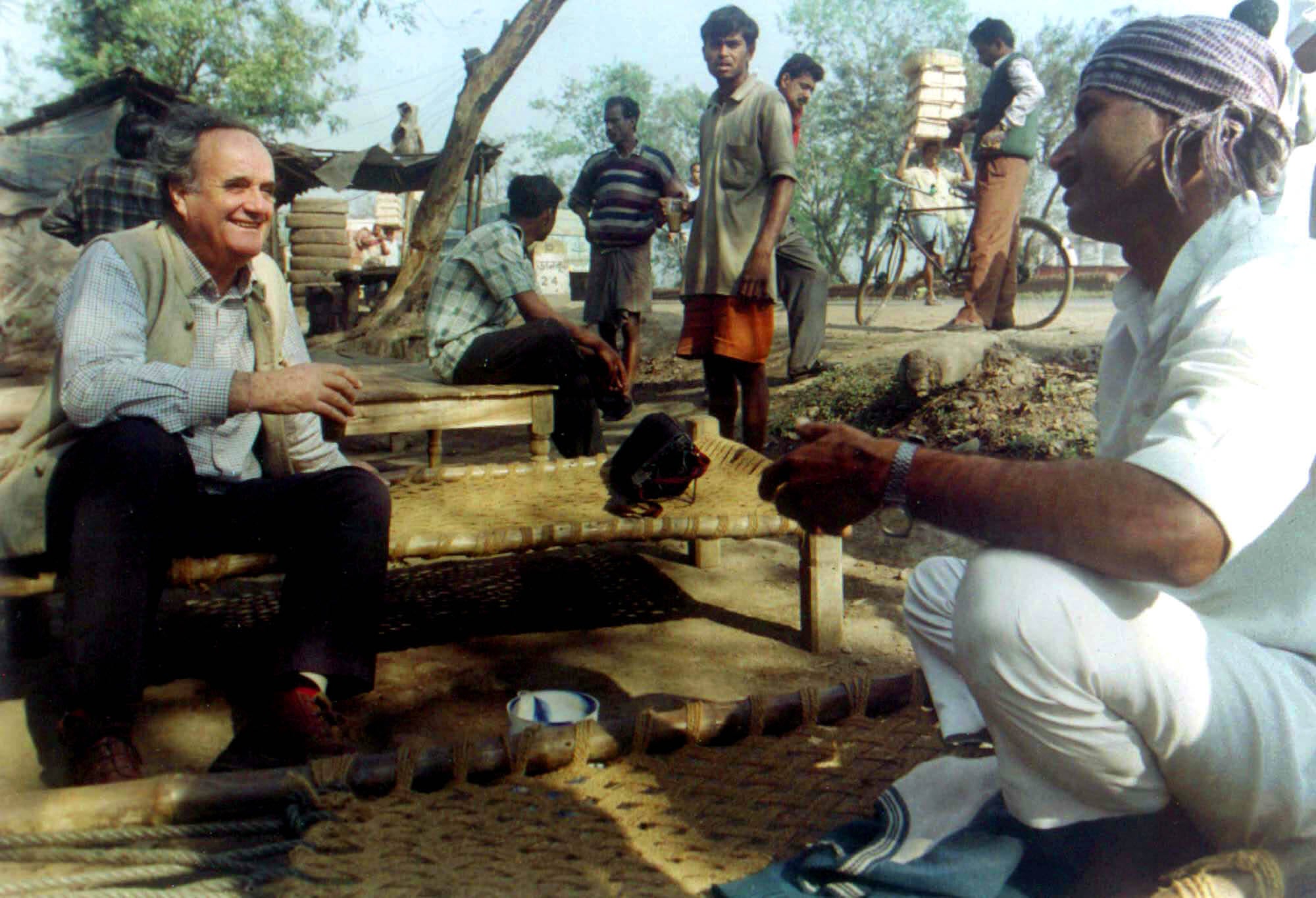

Mark Tully was more than just a foreign correspondent. The veteran BBC journalist was a familiar presence in India’s public life and a steady voice interpreting the South Asian country to the world. Tully, often hailed as the “Voice of India”, died in a Delhi hospital on Sunday after a brief illness. He was 90.

Born in Kolkata in 1935, Tully started his career with the BBC in 1965. Six years later, he was appointed the broadcaster’s Delhi correspondent and went on to spend more than 20 years as its South Asia bureau chief.

Tully covered some of the most pivotal moments in India’s modern history – the 1971 India-Pakistan war that led to the independence of Bangladesh, the 1984 siege of the Golden Temple in Amritsar, the 1991 assassination of prime minister Rajiv Gandhi, and the 1992 demolition of the Babri Masjid which sparked nationwide sectarian violence.

Tully also reported extensively from neighbouring Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, providing audiences with nuanced insights into the region’s complex political and social landscapes.

Soon as news of the veteran journalist’s passing broke, tributes began pouring in. Many argued that what set Tully apart was not merely access to power or breaking news, but his patience.

“He wrote not for an English audience, but for an audience of Indians and those in the West with a passing interest in India,” senior journalist AJ Philip noted in a tribute. “He had a deep appreciation for rural and small-town India. He was deeply suspicious of urban sophisticates which kept his reporting grounded and honest. His independence of thought helped him avoid the honeyed traps that have ensnared many journalists covering India today.”

Tully’s reporting often resisted easy conclusions, many noted. At a time when narratives about India were frequently reduced to binaries – tradition versus modernity, chaos versus order – he chose nuance, others said.

Beyond reporting, Tully captured his experiences in India in many books. Amritsar: Mrs Gandhi’s Last Battle, co-authored with fellow journalist Satish Jacob in 1985, explored the events surrounding the siege of the Golden Temple and its aftermath.

In India in Slow Motion and No Full Stops in India, he turned his attention to the rhythms of everyday life, offering readers a thoughtful, nuanced view of villages, towns, and the complexities of Indian society.

Tully’s exceptional journalism and deep engagement with India earned him recognition nationally and internationally, including a knighthood in 2002.

His reporting shaped how the world saw India and even how many Indians understood themselves, several commentators said.

“Mark said his passion for India was greater than his passion for journalism,” journalist John Elliott said in a tribute. “He was happiest travelling the country talking to contacts and reporting and commenting on radio what he saw and heard. Perhaps no one in living memory has spanned the two cultures of Britain and India as sensitively and closely as Sir Mark Tully.”

Tully was also unusual among foreign journalists in how openly he engaged with Indian society. He lived in the country for decades, spoke candidly about his own beliefs, and developed close relationships across political, religious and social lines. He also spoke Hindi.

“He did not of course advocate continuing poverty or a lack of development, but he refused to accept that Western-style consumerism and other forms of change were the way to achieve progress,” Elliott said. “He was also a virulent critic of the current Indian government’s Hindu nationalism.”

Many described Tully as a bridge between India and Britain, between rural and urban worlds, between reportage and reflection.

Indian prime minister Narendra Modi described him as “a towering voice of journalism” and added that “his connect with India and the people of our nation was reflected in his works”.

On Monday, friends and admirers gathered to pay their last respects at his cremation. Christian priests offered prayers before the rites were performed and the body taken for cremation.

“I first met Mark on a flight to Vishakhapatnam,” Jacob, the co-author of Tully’s book on Amritsar, wrote. “We shared a taxi to the areas devastated by the cyclone. It was the beginning of a friendship that lasted 48 years. We worked together for 16 years and stayed friends till the very end.”

“We both loved India, Irish Whiskey, food from Old Delhi and Cigars. Privately, he was a boisterous personality with a great sense of humour and over the years we watched each other’s children grow up, marry and set lives for themselves.”

He said one of his favourite memories was the day India won the Cricket World Cup in 1983.

“We were on the terrace on a warm summer night in June while our Old Delhi mohalla was celebrating the win,” Jacob recalled. That’s when he heard Tully’s distinctive voice shouting, in Hindi, “We won!”

“And there was Mark outside my house with a bottle of our favourite whiskey, dancing in the street celebrating India’s victory,” he said.

“He left an indelible mark on my life, and I am going to miss my friend.”

Political scientist Pratap Bhanu Mehta wrote in The Indian Express: “Mark had the distinction of being targeted by every political dispensation. He was expelled from India during the Emergency. His account with Satish Jacob, Amritsar: Mrs Gandhi’s Last Battle, has of course been superseded in parts, but it remains an indispensable starting point because it courageously asked two questions that were long evaded: About the machinations within intra-Sikh politics, and about the Congress party’s complicity in creating the tragedy of Operation Blue Star and its aftermath. During the violence surrounding Ayodhya, he was chased by a mob shouting ‘Death to Mark Tully’, merely for the act of reporting.”

Mehta called him the “only voice of Indian history as it happened”.

Historian William Dalrymple wrote on X: “Mark Tully was a giant among journalists and the greatest Indophile of his generation. He was also a uniquely warm, generous, gentle, kind and helpful man, at whose feet I was honoured to sit for many years as he patiently explained the subtleties & nuances of India.”

“As the voice of BBC India, he was irreplaceable, a man prepared to stand up to power and to tell the truth, however uncomfortable. Both privately and professionally, he will be much, much missed.”

In a statement, the Press Club of India expressed “profound sadness at the passing of its long-time member Mark Tully”.

The statement added: “Someone who was passionate about ground-reporting and a storyteller par excellence, Tully was one of the few journalists present in Ayodhya on December 6, 1992, and he broke the news of the mosque's demolition to the world.”

In its obituary, The Times wrote that when he was once described as an expatriate, Tully bristled: “Please don’t call me that. I look upon myself as an Indian.” After trips back to London, he would admit – half amused, half unapologetic – that his luggage inevitably contained Marmite, along with bacon, cheese and a bottle of Irish whiskey.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks