Animal farms in South-east Asia fuel an illegal trade in rare wildlife

In China and South-east Asia, thousands of animals from endangered species – bears, snakes, tigers – are kept in appalling conditions and butchered for their ‘exotic’ meat. There are now more tigers in farms than in the wild. Can this barbarism be stopped?

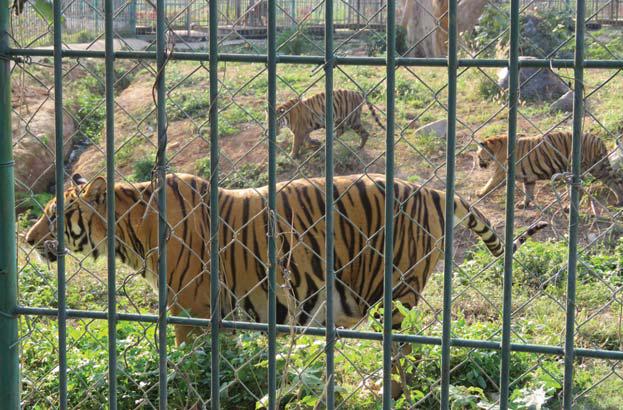

The tiger paces back and forth in its cage, groaning mournfully. A second big cat sleeps soundly in the corner, while a third stares blankly at the bars. Next to this cage is another containing three more tigers, and after that three more cages: a line of small pens, each holding at least one cat. Most likely, none has long to live.

The tigers are property of the Kings Romans Group, which operates a casino here, along with hotels, a shooting range, a cockfighting and bullfighting ring, a Chinatown-themed shopping center, and this shabby zoo. Ten years ago, the Hong Kong-based company signed a lease with the Laotian government to develop this 12-square-mile plot in northwestern Bokeo province, just across the Mekong river from Thailand. It’s called the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone.

Most businesses in the duty-free complex are owned and staffed by Chinese citizens and patronised by a predominantly Chinese clientele. Many are drawn here by the promise of vices not as easily found back home, including products made from exotic animals like tigers.

Conservationists maintain that this zoo is actually a farm raising animals for slaughter, and that it plays a significant role in perpetuating the illegal wildlife trade, swapping tigers with similar operations in Thailand and illegally butchering animals for their bones, meat and parts.

Tigers, bears, snakes and countless other species, many endangered, are held on farms throughout South-east Asia. Operators illegally capture animals in the wild and then pass them off as captive-bred, or breed the animals on site and illegally sell them into the trade. These facilities are part of a contraband industry whose profitability by some estimates is surpassed only by the global trade in drugs and arms, and by human trafficking.

Few tourists are present at Kings Romans during a recent visit. The ghost-town feel is reinforced by boarded-up shops, half-finished construction sites and posters advertising events that had long since come and gone. But restaurants at Kings Romans still offer expensive plates of bear paw, pangolin (an endangered scaly mammal) and sautéed tiger meat, which can be paired with tiger wine, a grain-based concoction in which tiger penises, bones or entire skeletons are soaked for months.

When a group of foreigners show up at the God of Wealth, Kings Romans’ fanciest restaurant, the suspicious proprietor tells their translator, “You can eat here, but do not ask for the special jungle menu” – the menu offering wildlife options.

Nevertheless, the staff offer tiger wine for $20 (£16) a shot glass, and serve a bear’s paw to patrons at a nearby table. In May, a photographer for The New York Times who visited the restaurant was offered plates of tiger meat for $45.

Nearby, half a dozen jewelry and pharmaceutical shops display exorbitantly priced tiger teeth and claws, as well as rhino-horn carvings and shavings, elephant skin and ivory.

“The place is just a mess,” says Debbie Banks, of the nonprofit Environmental Investigation Agency in London. “Pretty much anything goes.”

In 2015, Banks and her colleagues, along with the nonprofit group Education for Nature-Vietnam, reported that meals, medicine and jewelry made from numerous protected species – including tigers, leopards, rhinoceroses, bears and elephants – were openly sold in the special economic zone. Their documentation spurred the Laotian government to raid some businesses here and to burn a few tiger skins on television. But Banks said little had changed since that “cosmetic effort”.

Like the rest of the complex, the Kings Romans zoo is largely deserted save for animals kept in cages. A woman and her young daughter wander in to look at the bears. Many show signs of captivity-induced stress, including uncontrolled headbanging. Staff members are nowhere to be found.

Approximately 700 tigers live on farms in Laos. Thousands more are believed to be kept throughout South-east Asia, and an additional 5,000 to 6,000 are housed in over 200 breeding centres in China. Fewer than 4,000 of the big cats remain in the wild; farmed tigers now far outnumber total wild populations.

At an international conference on the endangered species trade last autumn, Laotian government officials acknowledged a growing problem with wildlife farms and committed themselves to closing down the country’s tiger farms. So far, little has changed.

One source who works closely with the government, who asked not to be named for fear of reprisals, said that some Laotian politicians remained deeply involved in the farms and that the country’s forestry department lacked the authority to shut them down.

Republican Representative Ed Royce of California, chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, has singled out Laos as an international hub for illegal wildlife trafficking, saying in 2015 it was “quite clear officials are profiting”.

Laotian government officials did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Treaty limits breeding

According to the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species, or Cites, a treaty to which China and all South-east Asian nations are signers, tigers are to be bred only for conservation – not for their parts, and not on a commercial scale that does not benefit wild tigers. In Laos and several other Asian countries, however, conservationists have compiled ample evidence that many zoos and farms serve as fronts for commercial breeding.

“Farming tigers for trade confuses consumers and stimulates demand,” says Grace Ge Gabriel, Asia regional director of the International Fund for Animal Welfare.

In 2016, Tiger Temple in Thailand made headlines when monks there were accused of abusing tigers and selling them into the illegal wildlife trade. Eventually, 40 dead cubs were discovered in a freezer, along with pelts and other wildlife products. Thailand has some 1,450 tigers in captivity, the majority of which are kept at popular attractions like Tiger Temple, where tourists pay to take photographs and play with cubs and young adults.

When the tigers reach sexual maturity and can no longer be handled safely, they often disappear, sold on the black market for up to $50,000 (£39,000), according to Karl Ammann, a Kenya-based investigative filmmaker who is making a documentary about the tiger farming industry.

Conservationists also have accused tiger farms in China – two of which are supported by government investment – of illegal activity. Chinese law permits some tiger skins to be traded legally, although tiger bone has been banned since 1993. But in 2013 Banks and her colleagues found that farms were stockpiling tiger bones to make wine and that skins from wild tigers were sold as being from captive-bred tigers.

After inquiries from the Times, Meng Xianlin, executive director-general of the Chinese Cites management authority, declined to be interviewed. Several other Chinese officials did not respond to repeated interview requests.

Past violators often re-enter the wildlife farming business. Construction has already begun on a zoo next door to Tiger Temple. Officials in Vietnam recently granted permission for the wife of Pham Van Tuan, a twice-convicted tiger trafficker, to import 24 tigers from the Czech Republic “for conservation purposes”.

Vuong Tien Manh, deputy director of Vietnam’s Cites management authority, says that Vietnam had seized a number of frozen tigers and tiger bones over the past five years, most of which were suspected to have originated from Laos. He adds that Vietnam’s policies did not permit commercial breeding of tigers, but the country has some 130 tigers in captivity. All tiger farms are strictly monitored, Manh says, no matter who the owners are.

Bear bile collected

Though tigers are the most contentious of Asia’s farmed wildlife, they are by no means the only species caught up in the industry. An estimated 10,000 bears are legally kept on Chinese farms for their bile, an ingredient in traditional medicine that is collected through a tube permanently implanted in the animals’ gall bladder, or through a hole in their abdomens.

Countless other species – crocodiles, porcupines, pythons, deer and more – are also farmed throughout China and South-east Asia. Some proponents, including government officials, believe that such facilities should be legal and encouraged, arguing that they relieve pressure to hunt wild animals by satiating demand with captive-bred animals.

Others say there is no evidence to back this assertion. “I can’t think of any species in South-east Asia that benefits from commercial captive breeding,” says Chris Shepherd, the South-east Asia regional director for Traffic, a nonprofit wildlife trade-monitoring group. Scott Roberton, the director of counter-wildlife trafficking at the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Asia program, adds that the risks associated with legalising trade in farmed tigers and other endangered species are the same as those associated for decades with the ivory trade.

“Legal trade stimulates demand, confuses law enforcement efforts, and opens a huge opportunity for laundering illegal products, which is why ivory markets are now being closed globally,” he says.

“There just isn’t the capacity within these countries to manage a legal trade in a watertight way,” Roberton says.

“Laundering” of animals as farmed that were actually caught in the wild is a frequent practice. In Chengdu, China, a third of 285 bears rescued from bile farms and now living at a rehabilitation centre run by Animals Asia, a nonprofit group, are missing limbs, a sign that they were caught in the wild by snares.

A 2008 investigation by Vietnamese officials and the Wildlife Conservation Society found that about half of 78 wildlife farms surveyed regularly launder animals caught in the wild. In 2016, a study of 26 Vietnamese wildlife farms found that all engaged in laundering. The pet trade is also a problem. Indonesia annually exports over four million reptiles and small mammals labeled captive-bred – including thousands shipped weekly to the US. But virtually all are caught in the wild, according to Shepherd. “I’ve been to almost every reptile farm in Indonesia, and none have breeding facilities,” he says. “Wildlife dealers are running circles around everyone. It’s a joke.”

Though modern wildlife farming emerged in the 1990s and has only grown in popularity, wild populations of farmed species have continued to plummet, Shepherd says. Tigers are effectively extinct in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam, while just seven to 50 remain in the wild in China.

“No matter how many tigers are farmed, we still have wild tigers getting killed,” he says.

What becomes of the tigers?

Heeding these arguments, Laotian government representatives attending a major Cites meeting last September announced their intention to end tiger farming in their country. International nongovernmental organisations are advising Laotian authorities on how to carry through with that announcement, but there has been no progress to date.

“There are some countries in South-east Asia that are equipped to combat criminal networks, and some that are still struggling,” says Giovanni Broussard, South-east Asia regional coordinator for the Global Program for Combating Wildlife and Forest Crime of the United Nations Office on Drug and Crime. “Laos,” he says, “is in the category of those that are still struggling.”

Though most tiger farms in Laos do not allow visitors, conservationists fear that owners will simply shift to a model embraced in Thailand, in which petting zoos serve as a front for illegal trade.

Even if the authorities move forward with shutting down the farms, what to do with the country’s 700-plus captive tigers is a challenge. Euthanising them would bring unwanted media attention, but releasing them into the wild is not an option. There’s not much prey, and the tigers lack survival skills and have no fear of humans.

Yet keeping them is a burden; it costs thousands of dollars a year to feed a single tiger, Banks says, and tigers can live up to 20 years.

In 2002, Vietnam faced a similar dilemma when it made bear farming and bile sales illegal. Fifteen years later, around 1,200 bears still live with their original owners. Many are kept in horrific conditions – in cages scarcely larger than their bodies, suffering from rampant disease and lacking adequate food and water – and their bile continues to be collected illegally.

Animals Asia runs a rehabilitation centre near Hanoi that houses 160 bears rescued from the trade, but the centre has permission to keep only 200 animals. Even if that cap were eliminated, however, the group lacks the funds and space to care for all of Vietnam’s remaining captive bears.

“Obviously, we can’t do this all ourselves,” says Tuan Bendixsen, Animals Asia’s Vietnam director. “The government must take responsibility for their wildlife.”

As Laos ponders how to responsibly close its tiger farms, China is moving in the opposite direction. Since 1992, it has been petitioning Cites to permit trade in farmed tiger products. When Chinese representatives lobbied for this change once again at the most recent Cites meeting, the proposal was turned down.

Conservationists believe that international pressure may be crucial to persuading Asian governments to close tiger, bear and other wildlife farms, but that strategy’s effectiveness is compromised by an awkward fact: An estimated 5,000 tigers are held in backyards, petting zoos and even truck stops across the United States.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks