Cape Cod homes are falling into the sea. But the celebrity haunt has never been more popular - or expensive

On Cape Cod, the sea level has risen about a foot in the past century but that hasn’t stopped people moving in, Louise Boyle writes

This article was originally published in March 2022

Across Cape Cod’s quaint towns and pristine sandy beaches, a taboo subject hangs in the salty air.

The sea level is rising, and at an accelerating rate. In the next 30 years - the typical term for an American mortgage - average US sea level rise is expected to be 10 - 12 inches (25-30cm) due to climate change.

On Cape Cod, the sea level has risen a foot in the past century, says Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Falmouth, Massachusetts, a threat that is being exacerbated by extreme storms pummeling the coast with heavier rainfall, storm surge and winds.

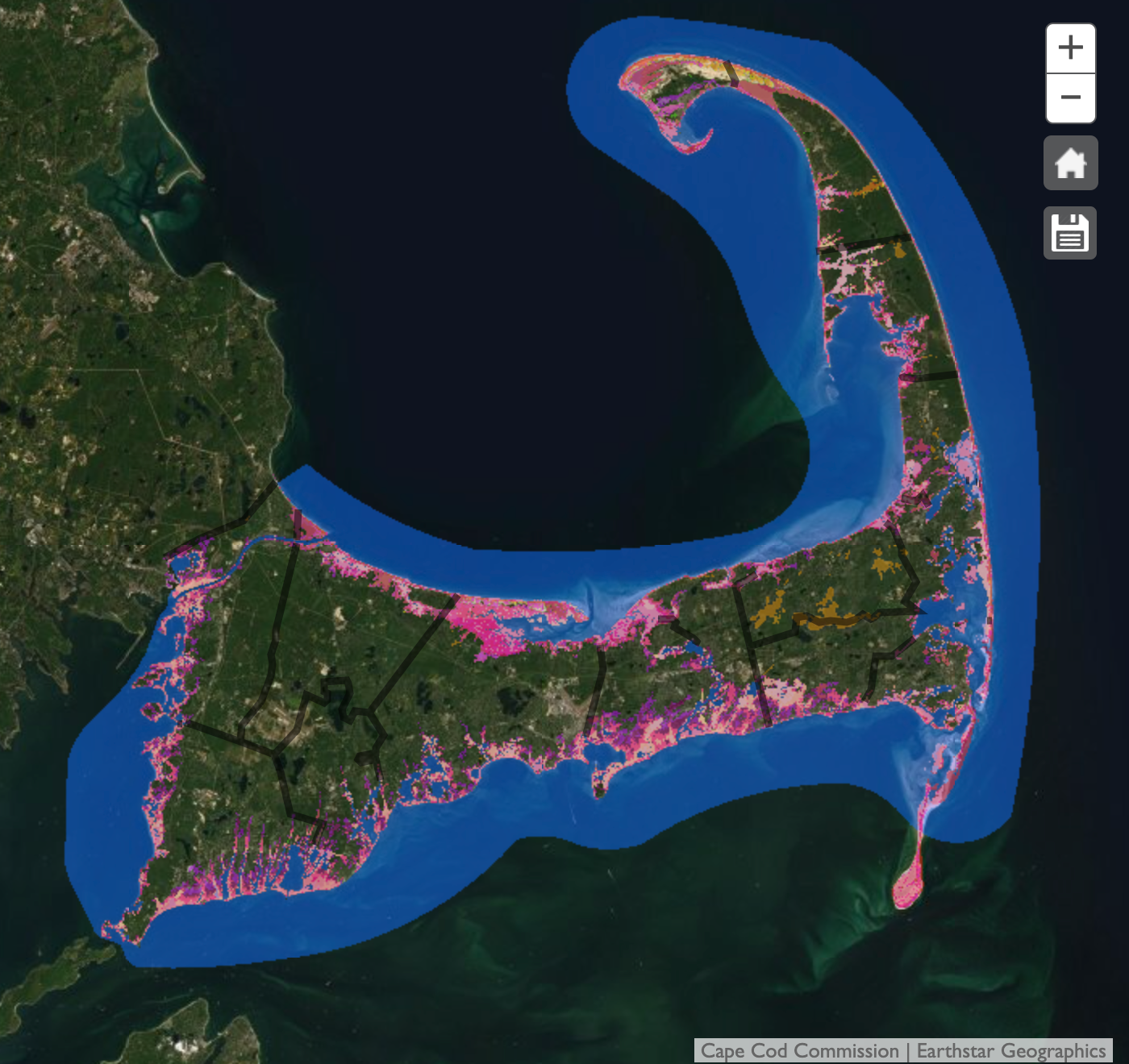

Last year, the Cape Cod Commission (CCC), which oversees environmental protection in the region, released a Climate Action Plan which found that failure to adapt to the climate crisis will be exorbitantly expensive. Up to 2030, damage to buildings will be approximately $69million a year. By mid-century, that annual figure jumps to $256m on average.

In a place with 600 miles of coastline on the edge of the Atlantic, impacts are already proving devastating.

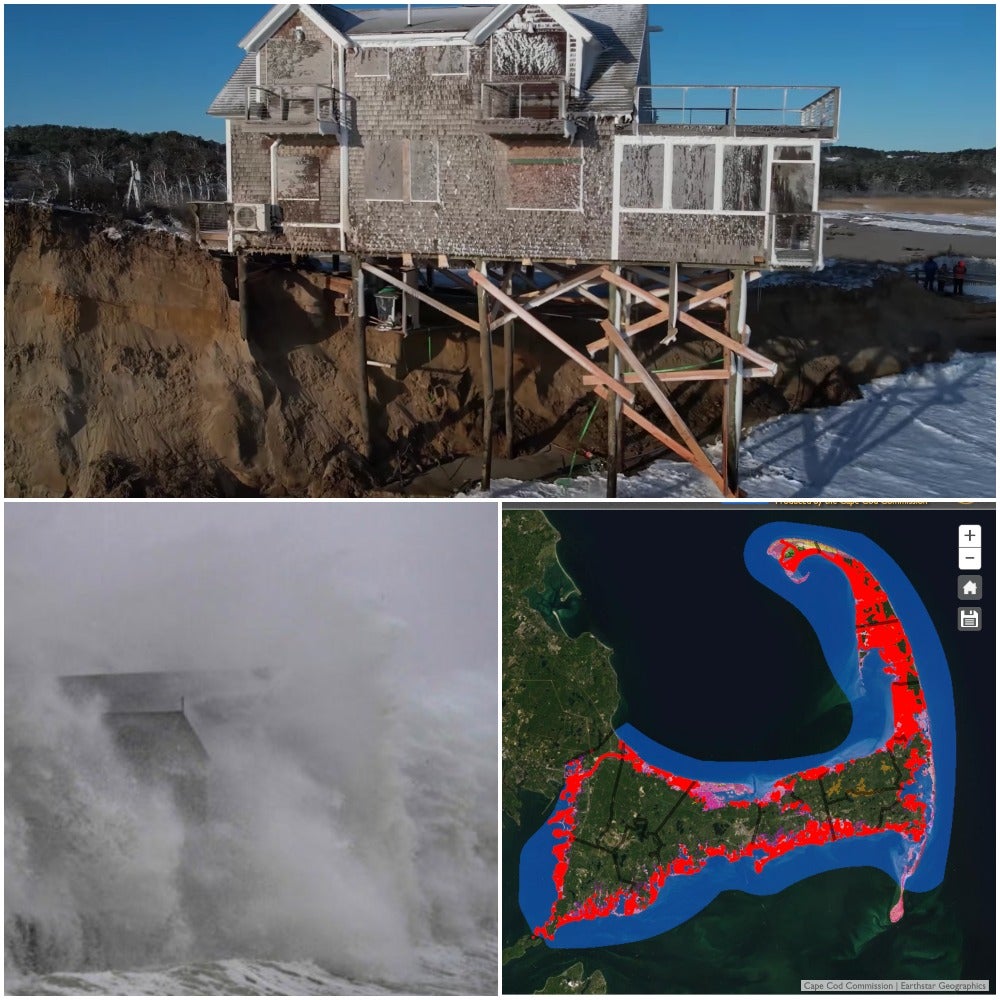

A home on Ballston Beach, built in 1850 as a Coast Guard station, was left teetering over the ocean following 100mph winds from a “bomb cyclone” in January. (The home-owners were later able to move the building further inland).

Others haven’t been as lucky. At least three homes in Sandwich, the oldest town on Cape Cod, were condemned after fierce waves eroded their supports and led parts to collapse into the sea, WCVB reported. For years now, erosion has left other homes stranded by rushing tides, with no choice for owners but to watch them wash out to sea.

The 100-year-old Nauset Light in Eastham had been moving progressively closer to the cliff edge due to coastal erosion until it was relocated in the mid-Nineties following a public campaign to save it. But the relentless ocean waves combined with January’s blizzard led to closure of its parking lot for public safety.

“As a rule-of-thumb, a sandy shoreline retreats landward (erodes) about 100 feet for every 1-foot rise in sea level,” the CCC climate report found.

“Therefore, based on local sea level rise projections, the Cape may experience between 400 to 1,000 feet of shoreline retreat by the end of the century.”

Greg Berman, a coastal processes specialist at Woods Hole, told The Independent that “retreat is kind of a dirty word for property owners” in the area.

“It’s very difficult to encourage that sort of thing and in some areas, it’s more feasible than others,” he said.

“That’s part of trying to adapt to climate change. Our sea levels are increasing, our erosion accelerates. How can we extend the usable lifespan of the properties that drive our tax base while at the same time having the least impact on the coastal resource areas that are of benefit to the public?”

It is a tricky balancing act in one of America’s most desirable areas. The Kennedy family have a compound in Hyannis Port, the Obamas own a place on Martha’s Vineyard, the Bidens spend every Thanksgiving on Nantucket. Celebrities including Taylor Swift, Meg Ryan, Harry Connick Jr and Tommy Hilfiger have had homes in the area.

It’s not difficult to see what makes it magical. Cape Cod has more than 130 beaches set against dramatic cliffs, a quirk of its shape created by a glacial feature some 25,000 years ago. The topography also means that it has always been subject to natural erosion and constant reshaping by the ocean waves.

“All our [sediment and sand] was brought down by glaciers,” Mr Berman says. “In places like Louisiana, for example, a lot of material is brought down by rivers but Cape Cod has streams and very small water bodies so it’s not getting that influx.

“Parts of Chatham and Provincetown [towns on Cape Cod] weren't around 6,000 years ago. It takes the erosion of areas like Ballston [Beach] and mobilization of that material to the north and south to create the rest of Cape Cod.”

But climate change is bringing a host of new issues on a much shorter timescale to the Cape - a fact that has done little to deter an influx of new people.

In the first year of the pandemic, 6,800 homes sold on Cape Cod. In one town the median sale price for a home leapt 218 per cent, from $557,500 to $1.78 million.

The county saw quadruple the number of new residents in 2020 compared to 2019, with the majority planning to be full-time residents, a recent survey found. Nearly 200,000 people live on the Cape year-round.

Erin Perry, deputy director of the Cape Cod Commission, told The Independent that 15,000 properties are located on Cape Cod’s floodplain and while they don’t face the immediate threats of oceanfront properties, they are still proximate to the coast and subject to significant storm surge.

“Sea level rise is impacting those properties, or is likely to in the future,” Ms Perry said. “When you look at those properties in the floodplain, they’re worth $16billion in assessed value in total. It’s a significant threat.”

The impacts of climate change are undeniable at this point, she noted. “We’re losing houses in most of these major storms now, it’s just very telling.”

Part of the challenge in adapting to climate change also comes from the types of properties now being built.

The next generation who inherit land with a small family beach hut - or the wealthy newcomers they sell to - may have much bigger ideas. And with that comes much bigger, much more expensive, problems.

“A small captain’s cottage built hundreds of years ago was always designed so, if it got wiped out by a storm, it got wiped out. Or if the beach got too close, it was hauled back for a while,” Mr Berman says.

“Now, it’s called McMansion-ing in certain areas. The value of the land underneath those houses has become so expensive, and the houses themselves have gotten so expensive and substantial, it’s not as easy to move them. Folks are very unwilling to allow that retreat anymore. And it’s expensive when they get damaged.”

And in some places, residents’ efforts to protect the shoreline near their homes by constructing sea walls had the unintended consequence of worsening erosion in other parts of the coastline by blocking the flow of sands.

It’s not just Cape Cod’s homes that will be impacted if the area doesn’t better adapt to sea level rise, storm surge and erosion.

“The [climate report] estimated that through the end of the century, we could see $50bn in losses from damaged roads, lost tax revenue, beach tourism loss, decreased land value, and building damage,” Ms Perry said.

Currently, nearly half of Cape Cod bridges are in need of repair, The Cape Cod Times reported in November but of critical importance are the Bourne and the Sagamore bridges.

Built in the 1930s, they are the only vehicle access to Cape Cod and have long exceeded their life-span. Just one severe storm could damage either or both bridges, leaving residents cut off from the mainland. (Ms Perry says that addressing the bridges is a priority for local officials). The commission is also working with ten communities over the next year to examine vulnerabilities in Cape Cod’s low-lying roads.

While not adapting to climate change will cost billions of dollars, the commission’s report acknowledges that making necessary changes will still have a “significant” price tag.

“Financial resources will need to come from a variety of sources, including the local, state, and federal level; and new and innovative financing strategies will need to be explored,” it reads.

Among the relatively lo-fi, low-cost solutions is creating green infrastructure which bolsters shorelines and protects the homes along it. Planting native vegetation like seagrass and adding coir logs - made of shredded up coconut husks - create a “living shoreline” which buffers the land from powerful waves and slows down erosion.

With the Coir system, in particular, says Mr Berman, “the hope is that it biodegrades over time, and allows that living root mass to connect down to the underlying strata, restabilising in a more natural way”.

The added bonus of these natural solutions, compared to bulkheads or seawalls, is that plants create habitat for marine life and sequester carbon from the atmosphere.

There is an ongoing “nourishment” schedule for beaches with sand being dredged from the Cape Cod Canal to bolster the shoreline and create dunes.

When it comes to properties, the report found that flood-proofing and raising buildings may be cost-effective when it comes to dealing with storms in the coming decades. Raising buildings, for example, sees a benefit of $3-$5 for every dollar spent.

In the long term, particularly for homes with high risk of inundation and where access becomes more and more difficult, retreat and possible buyouts may be the only options left.

Moving buildings should “potentially be reserved for historic or culturally valuable buildings” that cannot be protected from sea level rise, the report found.

“With more properties becoming vulnerable to erosion or flooding, and potentially becoming hazards along the coast, the federal and state governments are allocating funds and setting up programs to buy-out properties, with willing sellers, and remove the development from the shoreline,” says the commission’s report.

In California, some communities are buying up coastal properties from owners and renting them out short-term to fund a long-term path of retreat.

“We're looking to extend the usable lifespan of a property and sadly, everything has a lifespan,” Mr Berman says. “If a house was built 500 years ago, in some areas, there's no way it could have been kept in place. The sea has changed.

“What is the make-or-break point for coastal retreat? In a lot of areas, we're having that conversation. But who is going to pay for it is probably the biggest hang up. It's the multibillion-dollar question.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks