Fierce debate roars into life over the right to hunt grizzly bears

A bitter row has erupted over the British Columbia government's recent decision to end grizzly bear trophy hunting. Here are the pros and cons of stopping the hunt

There’s no shortage of controversy surrounding the British Columbia government’s decision to stop the grizzly bear trophy hunt. The province announced in late August that it’s moving towards permanently closing grizzly trophy hunting by the end of November, with immediate closure in the Great Bear Rainforest. Hunting grizzlies for their meat is still permitted.

Supporters of trophy hunting view the ban as a political decision that ignores scientific information, diminishes economic opportunities and tarnishes hunters’ reputations.

Opponents applaud the ban, arguing the hunt is outdated, lacks concrete evidence to support its existence and is barbaric. Certainly the ban could signal changes for future grizzly bear management across other jurisdictions.

A North American debate

Outfitters in the Yukon have already raised concerns, calling for more scientific studies to inform bear management decisions. Alberta may also face increased scrutiny and pressure to reconsider a grizzly hunt in light of research on bear populations and public tolerance for conflict.

There’s also controversy about hunting grizzlies in the United States, with Yellowstone’s recent decision to remove the bears from their endangered status list and the move to stop protecting bears on Alaskan reserves.

So what to make of these arguments for and against trophy hunting grizzlies? Is trophy hunting a legitimate management tool? And is it even ethical to control the grizzly population that way?

Hunters say bear populations must be kept under control. Supporters say trophy hunting is an effective population management tool, and can help mitigate human-bear conflicts. In BC, trophy hunters say grizzly bears are the most closely managed and conservatively hunted species in the province.

Prior to the ban, the former BC government released a 2016 scientific review on grizzly bear hunting and said adequate safeguards were in place to ensure long-term stability of bear populations. However, habitat loss was instead noted as a significant challenge, and improvements in monitoring bears were required.

The review also noted BC produced more DNA-based population estimates for grizzlies than any other jurisdiction. Consequently, hunters argue bear management must be informed by science rather than opinion or emotions.

Even the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) has suggested “in certain limited and rigorously controlled cases … scientific evidence has shown that trophy hunting can be an effective conservation tool.”

Hunting male bears

This view is supported in other literature, with some researchers adding a regulated bear hunt may increase public acceptance of living alongside grizzly bears. However, this could also be perceived as giving people the power to manage problem bears as they deem fit — not necessarily a palatable concept for everyone.

Biologists also point out that trophy hunters generally target male bears because they’re bigger, and that may not pose the greatest threat to the grizzly population as it would if female bears were the primary focus.

Of 73 licences allocated in 2005 for grizzly bear hunting in Alberta, only 10 bears were hunted and killed. Instead, poaching, death after being mistaken for the more common black bears and roadway collisions may pose greater risk.

In BC, however, opponents contend that hunting kills an average of 297 bears annually. Opponents also argue that the lack of monitoring hunting raises serious questions about whether it’s an effective way to control the grizzly population or reduce bear-human conflict.

Is it a management tool?

A 2015 study on brown bears suggests hunting bears has negative indirect effects on the bear population, particularly cub mortality. Additionally, the same authors found that because hunting is not evenly distributed across bear habitats, social structure can be destabilised, and in turn this can impact the population.

As for conflict reduction, a 2016 study found that bear hunting did not reduce the frequency of bear/human confrontations. Human behaviour and poor garbage management were likely conflict culprits. A 2009 study, meanwhile, suggested the complex life histories, behaviours and social systems of animals like grizzlies mean any predictions that scientists make about trophy hunting as a management tool are unreliable.

Bear-viewing more lucrative?

Economic opportunities are also commonly raised in the grizzly hunt debate. Guide outfitters in BC say hunting has brought in more than $350 million annually (for bears and other wildlife) from national and international hunters. Some say the ban will result in lost revenue, affecting not just personal livelihoods but entire communities.

Additionally, outfitters caution bear-viewing could result in habituation, meaning bears become overly comfortable with human presence and therefore pose safety risks.

Opponents, however, argue trophy hunting is a corrupt practice globally, where revenues are unfairly or disproportionately meted out across communities and only benefit a few. Furthermore, they say a live bear is far more economically valuable than a dead one. The Centre for Responsible Travel found more revenue was generated from bear-viewing in the Great Bear Rainforest, and provided more job opportunities.

Swapping bullets for binoculars

Some outfitters suggest the hunting ban wouldn’t affect their businesses, because they’d shift to bear-viewing. Some BC resorts have already encouraged hunters to trade in their bullets for binoculars as an incentive to never hunt grizzlies again. Opponents also believe trophy hunting is immoral and wasteful. To some, it’s inconceivable to kill an animal for sport.

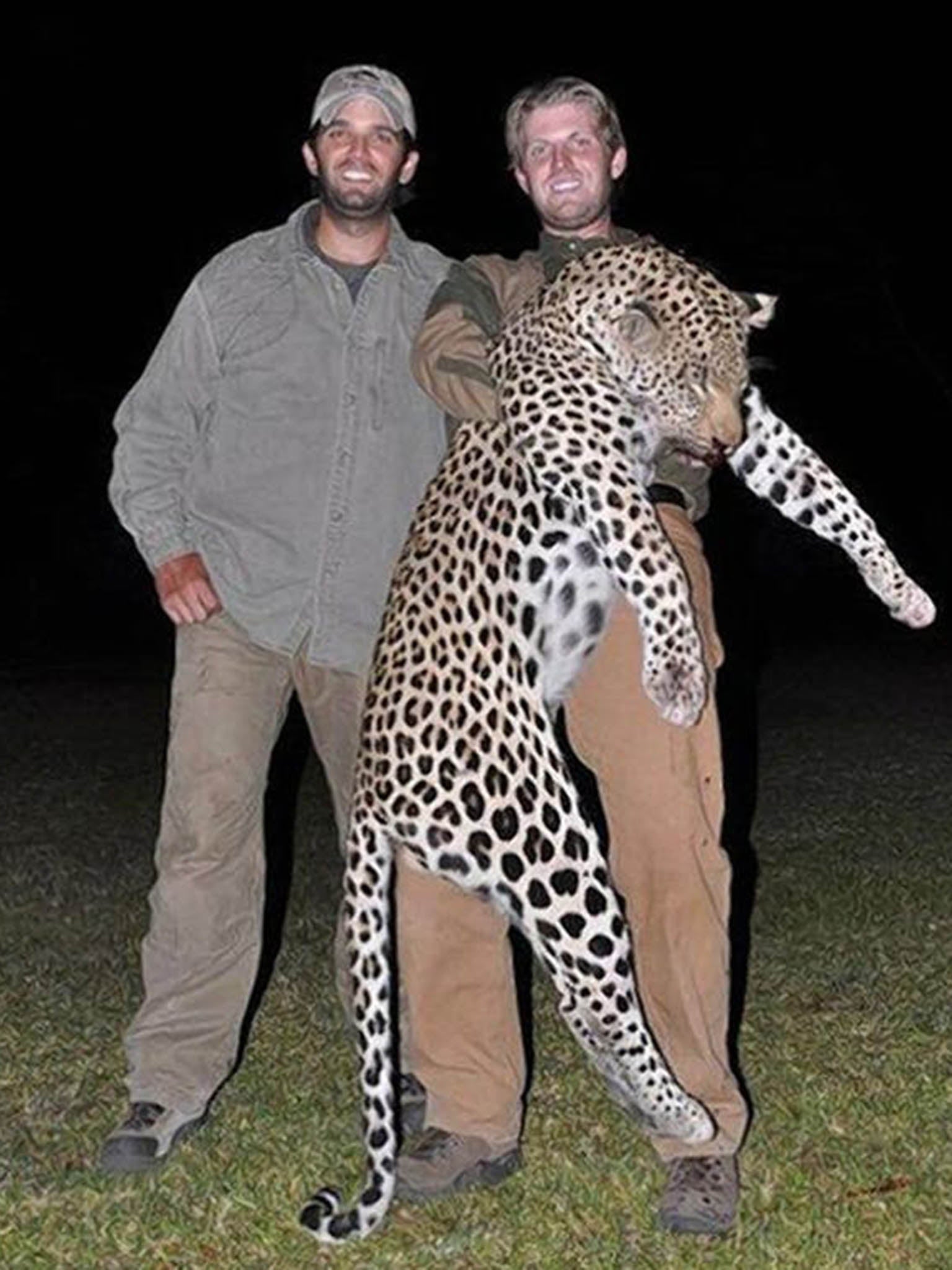

Many were disappointed in the BC trophy hunting decision because they’d hoped for a complete ban on grizzly hunting, particularly since the animals are not commonly eaten like elk or deer. Hunting of animals that are consumed as food is regarded as less offensive. On the motivations of trophy hunters, studies suggest the “prospect of displaying large and/or dangerous (animals) at least in part underlies the behaviour of many contemporary hunters.”

The same authors suggest men who hunt carnivores are signalling they can afford it, which helps them accrue status and attention, particularly from potential mates.

So, what are wildlife managers to do when society remains so deeply divided on trophy hunting? Who gets to decide how grizzly bears should be managed? This debate is certainly not new to wildlife management, and has become an increasingly contentious topic as biologists, policy-makers and the broader public ponders how to govern the animals that share our planet.

What’s next?

In BC, the government has attempted to temper the debate by permitting hunting grizzlies for meat, despite compliance concerns. In the Yukon, there’s a call for more studies to help inform decision-making, and our ongoing research, not yet published, has found some in rural Alberta are asking questions about reopening a grizzly hunting season.

Perhaps trophy hunting isn’t the greatest threat to North America’s grizzly bears. Certainly, habitat loss and population fragmentation, as well as climate change, pose even greater risks.

That’s why now, more than ever, we need consolidated action to manage grizzlies — not more argument. If we want grizzly bears to remain in our future, we need to set aside our differences and find some common ground.

Courtney Hughes is a conservation biology PhD candidate at the University of Alberta and Lindsey Dewart is an assistant researcher at the University of Alberta. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks